Secure Computer Systems

Database Security Multi-level

6 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Database Security Multi-Level

Multi-Level Security

Intelligence/DoD might have things they store in a database where they want multi-level security. Companies might have labeled data.

The BLP model can be applied to databases for multi-level security.

- We can read at the same level or at levels we dominate.

- We can write to the same level, similar to SELinux.

- Trusted users can violate these rules.

Access Class Granularity

Here are some different levels of granularity:

-

Database

- This is all of the data, multiple related tables

-

Table/relation

- This is a single table in the database, columns and rows. The lectures use relation a lot, remember that this is a table!

-

Tuple

- A row in the database

-

Element/attribute

- A cell in the database.

We can compute the access class of a tuple/table/database using the access classes of the elements/attributes within.

BLP in Sea View

Access classes are at the attribute/cell level. The tuple access class is the LUB/max (least upper bound, discussed in BLP section previously) of the attributes in the tuple.

Table access class is the GLB/min (greatest lower bound) of the elements within. The reason it is the greatest lower bound is because if a user can access some cell in the table we should allow them access to the table so they can at least view that cell.

The Database access is the GLB of the tables.

Example

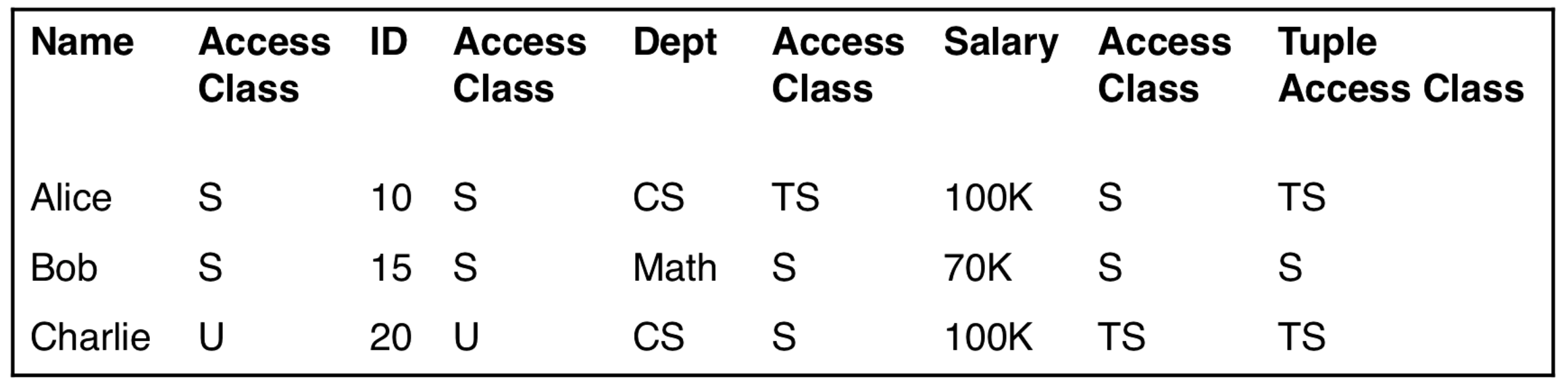

In the diagram below, each element has its access class directly to its right. So Charlie's salary is TS (Top Secret). The last column is the tuple access class, and it is the LUB (the max in this case).

The table access class is the GLB/min of all elements, which is U.

Entity Integrity

Data in a tuple of a relation is accessed via its key. To access the tuple we require that you can access the key. This leads to the following requirement, known as the entity integrity requirement:

Key access class access class of any non-key element of the tuple.

Multi-Level Relations

A user U has an access class c. There is a multi-level relation R which has elements of varying access classes.

U can only view the elements with access classes dominated or equal to the class of U, c.

The relation R has instances for each access class level c. For a database in state s we denote this Instance(s, R, c), the instance of R for a database with state s for user with access class c. All data elements are dominated by or equal to c.

If an element is not dominated by c then the element is replaced by the null value and has an access class equal to the key for the tuple.

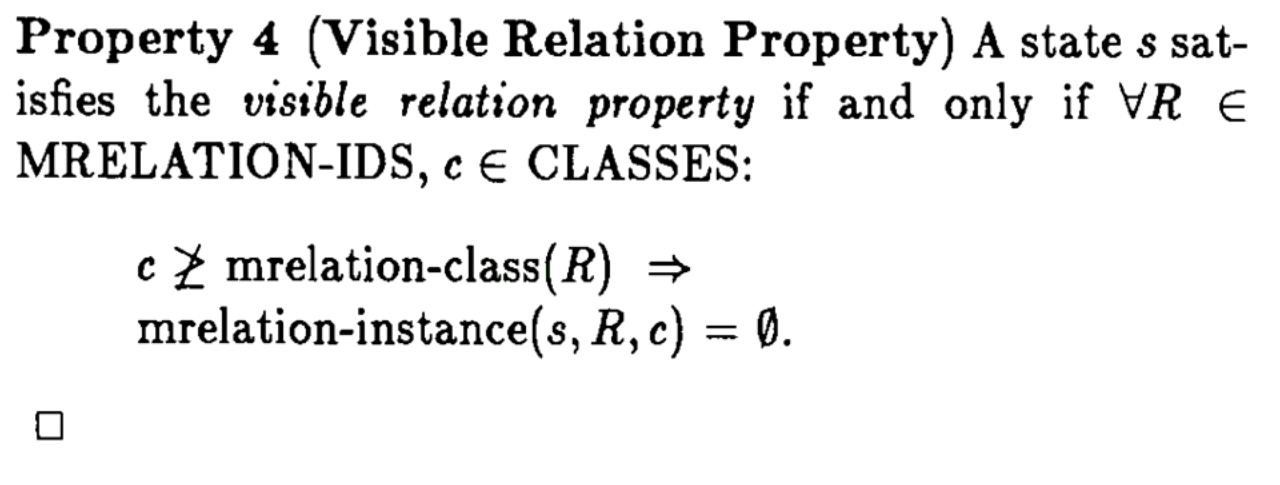

The relation has an access class which is the GLB/min of the elements. If the relation is not dominated by or equal to c then we cannot view the relationship at all. Here is the statement from the Sea View Model paper by Denning and Lint.

Inter-Instance Integrity

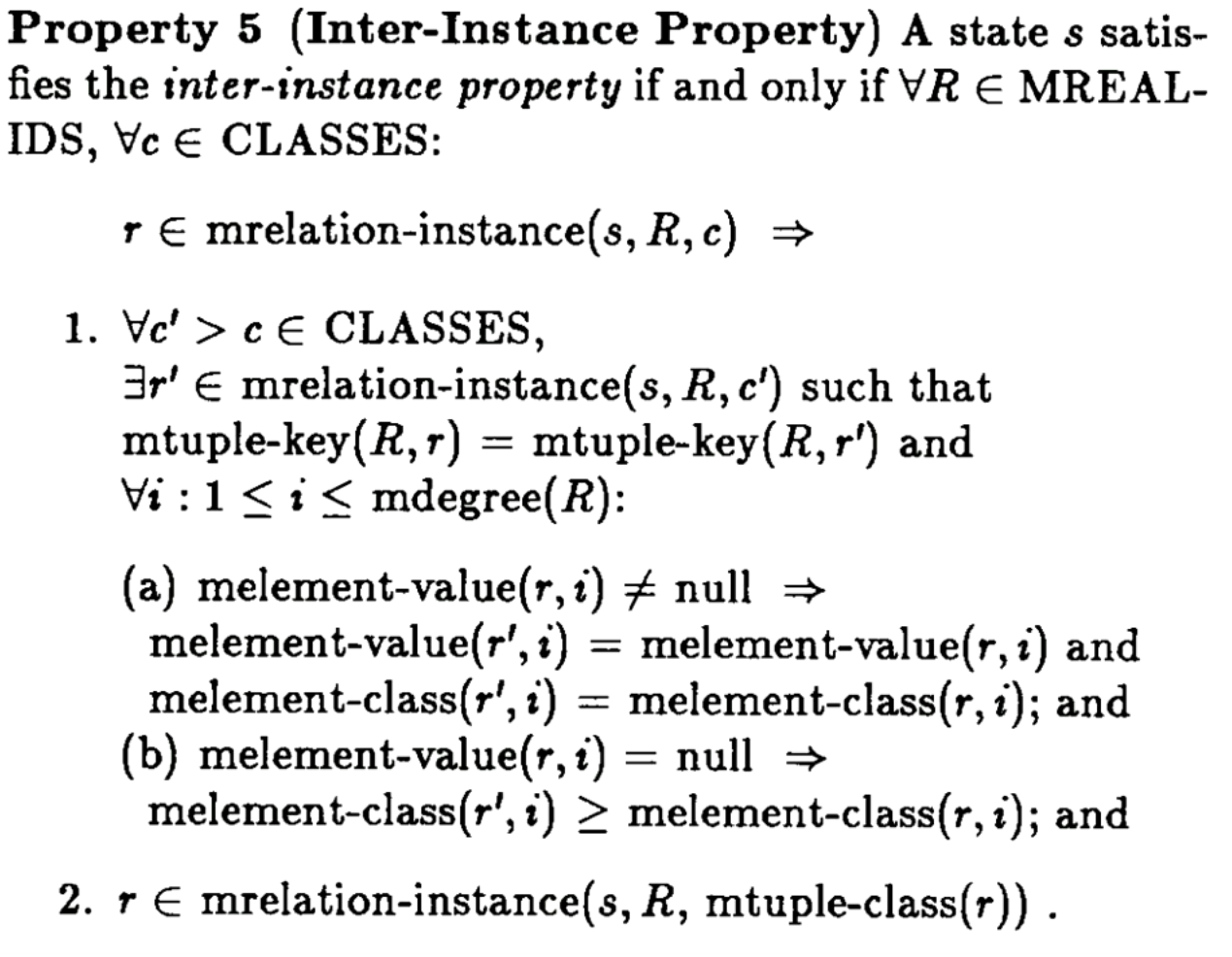

Recall that the access class of the tuple is equal to the max of the access classes of its elements. If a tuple r (lowercase r is used for tuples) has an access class c then all of its elements are visible when the access class c. If the access class is \< c, there will be some null values. We can go down to the access class of the key, which is the lower bound of access classes in the tuple, any lower and we will not be able to access the tuple since we can't access the key.

Below statement 1 can be paraphrased as

If a value is not null when viewed by a user in class c then a user in a dominating class c' will be able to view the value as it is and see the same class as the user in class c.

If the value is null for a user in class c, then maybe the user in dominating class c' will get to see the actual value. If they do get to see the actual value they will also see the actual class associated with the element. The actual class of the value will be greater than the key's class, since it was previously censored.

Statement 2 is saying that a tuple is in the relation having the class of the tuple.

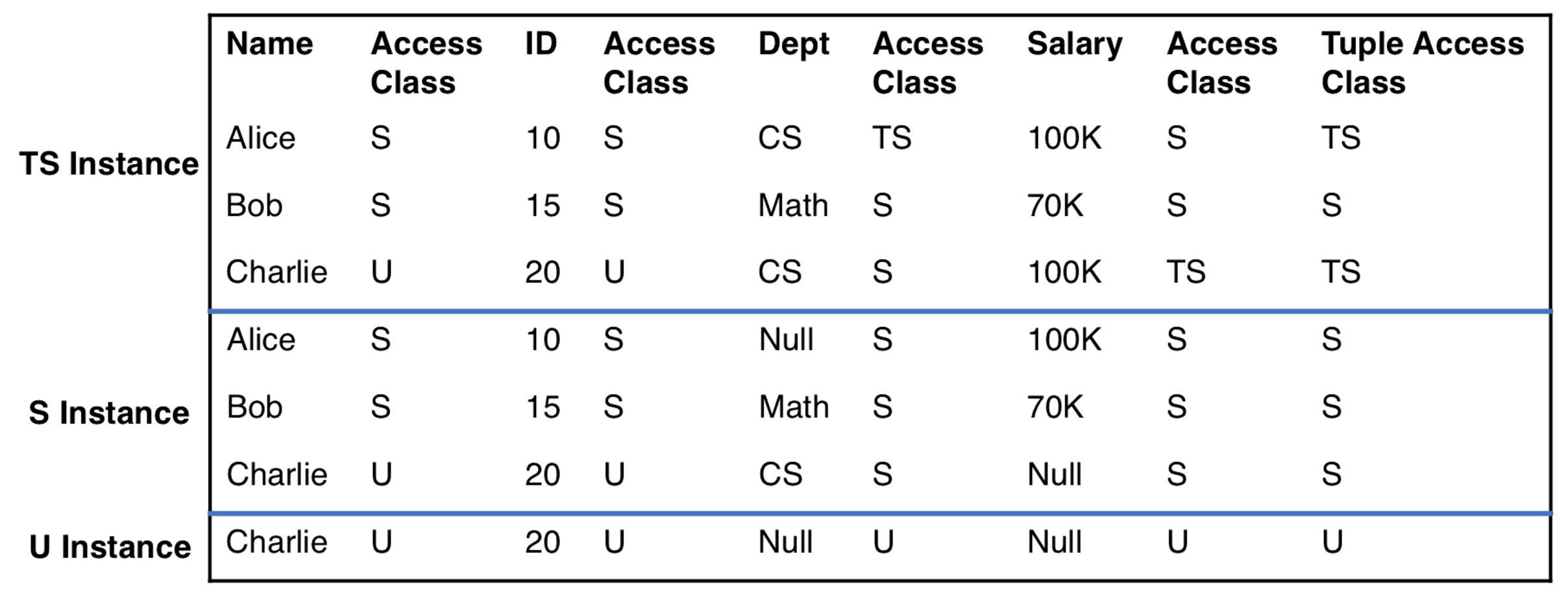

Here is a diagram of the same instance across different instance classes. See how some values become null going from TS to S, and that some rows disappear going from S to U.

Poly-instantiation

How this works is that we can "poly-instantiate" a tuple, meaning there are multiple tuples with the same key but at different access classes.

Usually we can't have multiple rows with the same key, but this there is a special situation called poly-instantiation.

There are two types of poly-instantiation -

- Visible: A lower access class value is visible to higher access class users, we write to this same value and it now is at a higher access class, but we keep the old less sensitive value in the database (not overwritten). A new tuple is created.

- Invisible: A higher access class value is not visible to a lower access class user (i.e. NULL) but we write over the null value. This doesn't change the actual value for the higher access class, but it creates a new tuple.

Examples

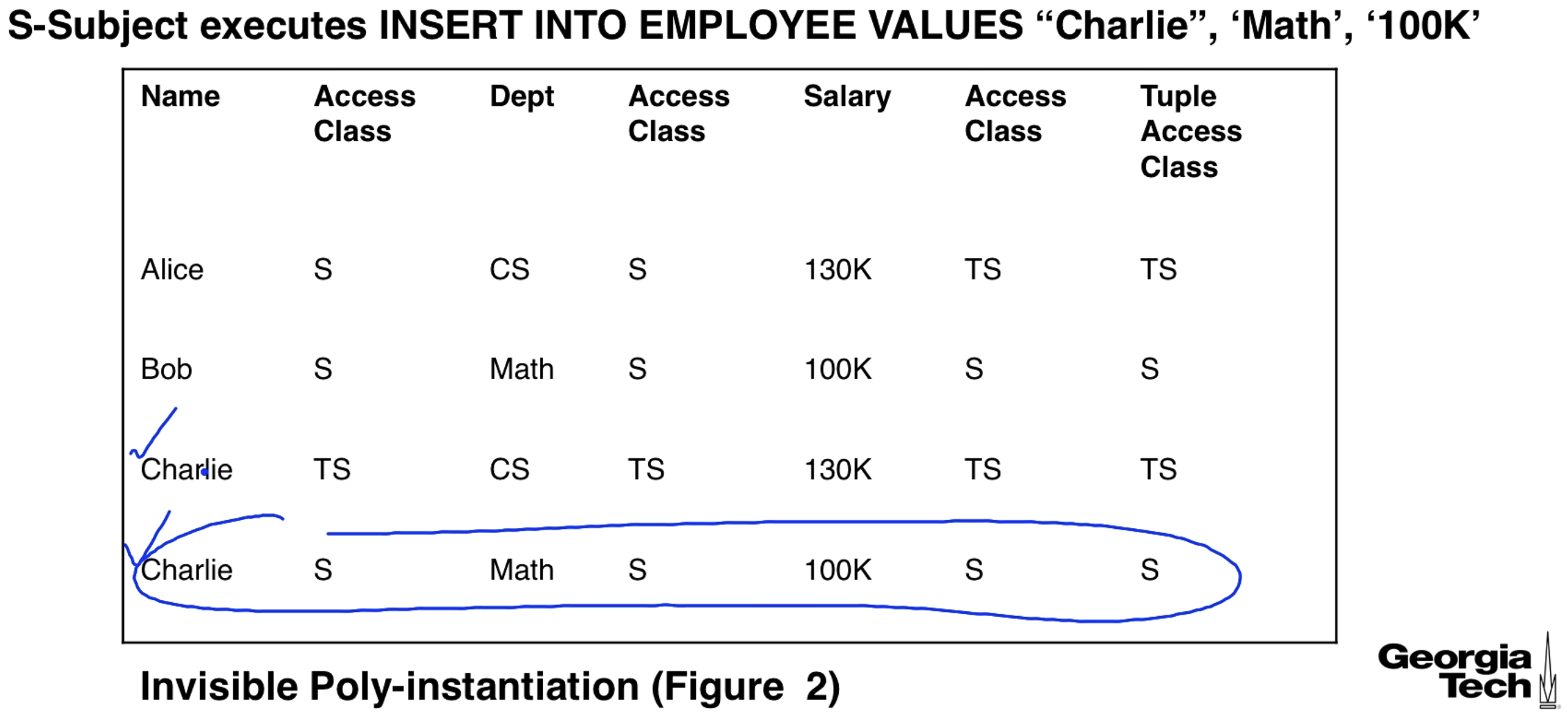

We can have a subject with secret clearance insert a row for Charlie into a table where there already exists an entry for Charlie, note: we assume that name is the key of the table. This poly-instantiates a row for Charlie, and it is invisible since the person inserting the row couldn't see the original row at all.

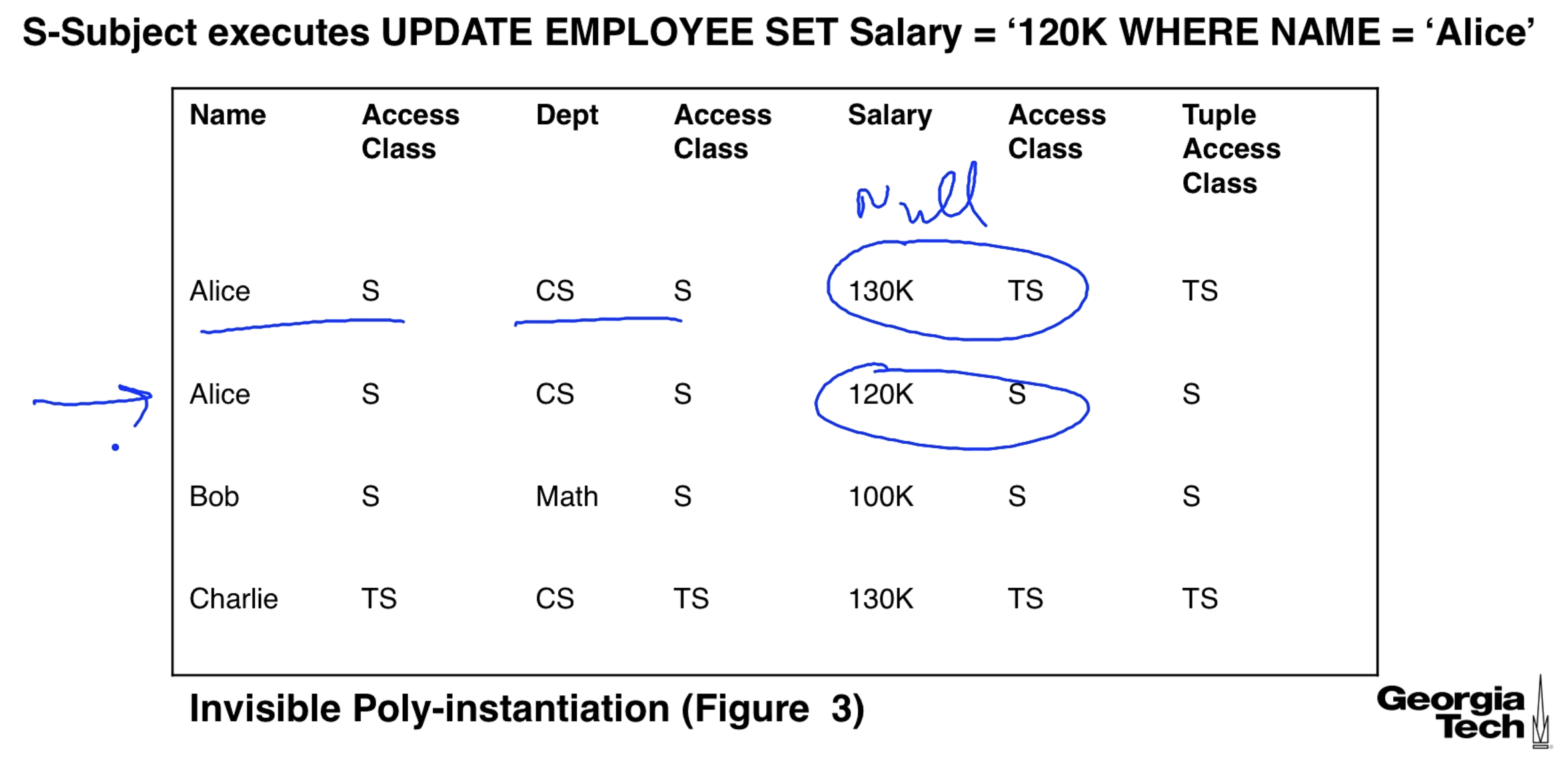

We can also do invisible poly-instantiation with an update. In this case the person doing the update can see the row but only sees a null value for the salary. They can update the salary to be not null, and this will poly-instantiate a new row.

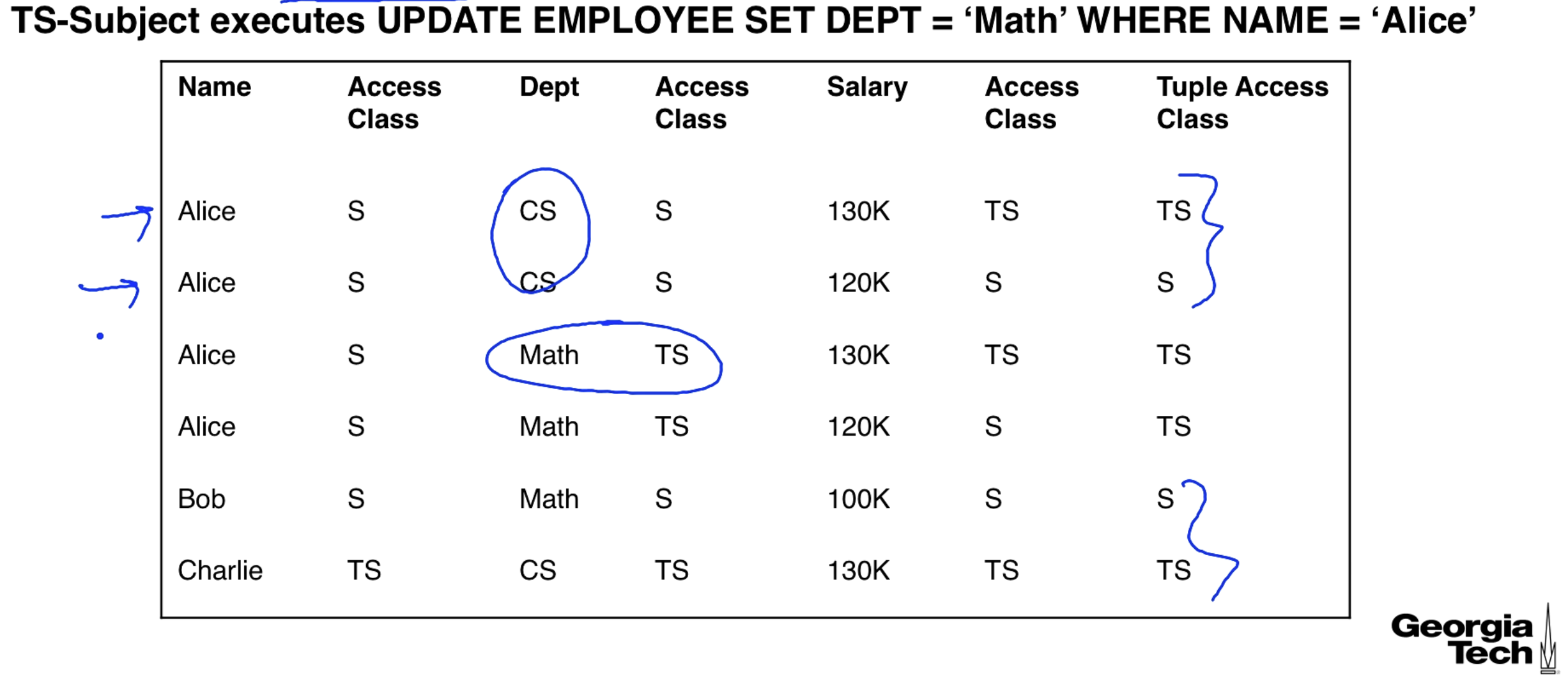

In our previous example we created 2 rows for Alice. We now double that to 4 rows. Notice that the UPDATE is applied to all rows with NAME = 'Alice'. A TS user changes Alice's dept. to math for the two existing rows.

Multi-valued Dependency (MVD)

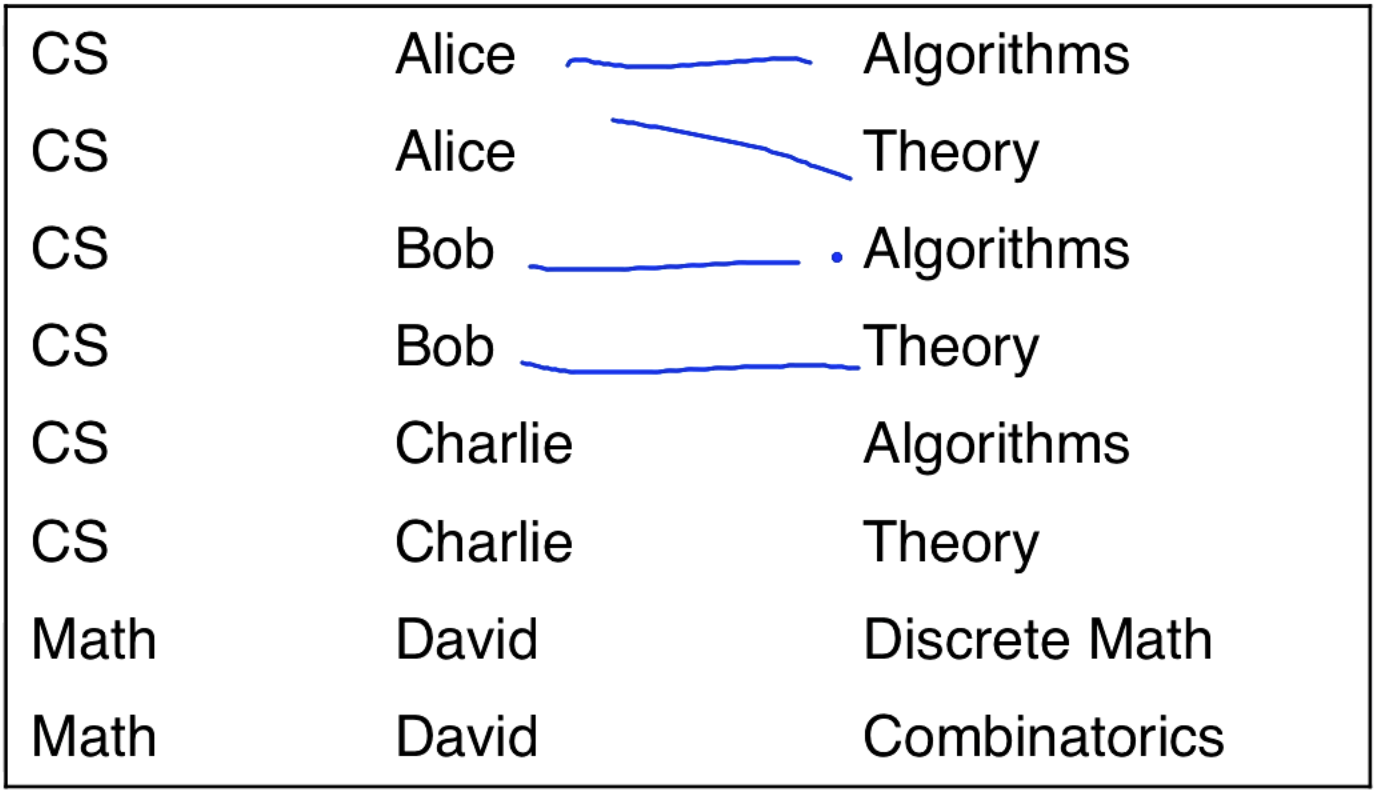

Maybe we have three columns, class, professor, book. So for each class if we have two recommended books then we are going to have two recommended books for each professor who is associated with the class.

More formally, if (class1, prof1, book1) and (class1, prof2, book2) are in the relation, then (class1, prof1, book2) and (class1, prof2, book1) are also in the relation.

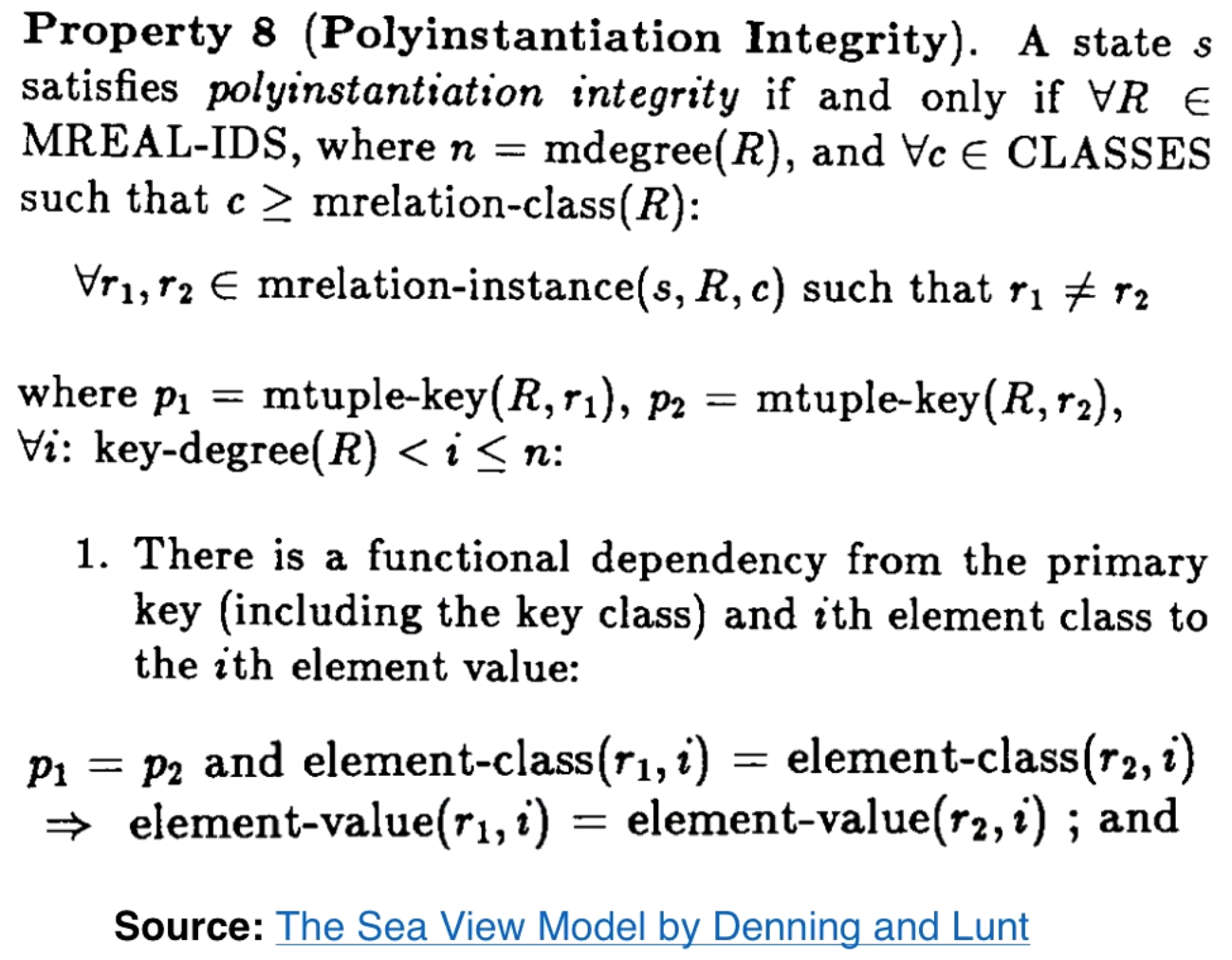

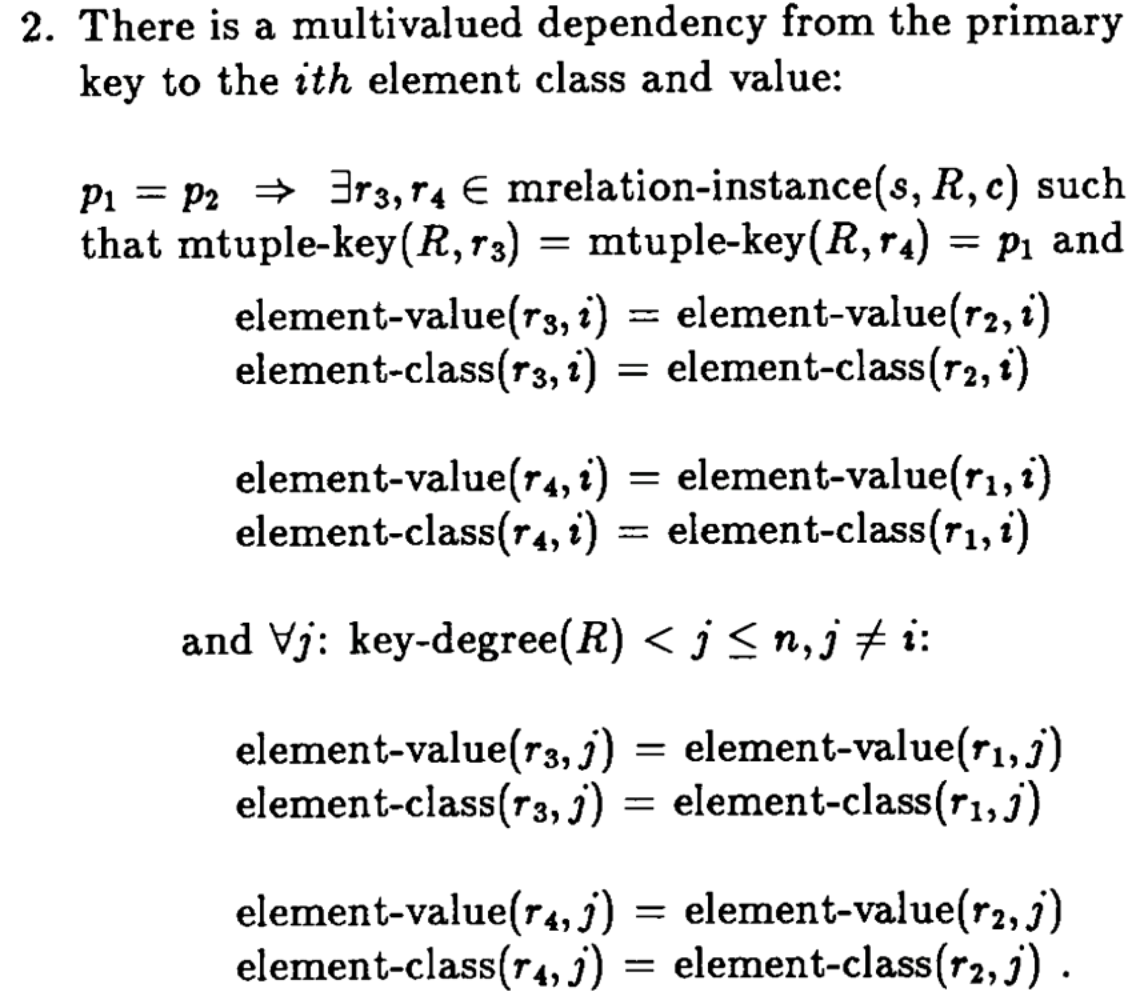

Integrity

This says that if two rows have the same key then values in the same columns of these rows having the same access classes will be the same. Look back at our example with 4 rows for Alice and see that values in the same column with the same access class and key are the same.

This is the multi-value dependency thing from before. Not entirely clear myself on the formalism, PRs welcome from passionate learners.

Jajodia and Sandhu (JS model)

In Sea View we can get tuples where Z = number of access classes and n = number of non-key elements. This is because for each access class you can multiply the number of existing rows by Z. So we start with 1 row, make updates for every access class to a single column and now we have Z rows. Do it again and we have Z*Z rows. Then we get up to tuples.

Jajodia and Sandhu made the JS model in a paper. The authors felt that some of the tuples generated in the Sea View model were not needed.

-

Entity integrity

- No Tuples can have null as part of the primary key (PK might have multiple elements)

- All key attributes have the same access class (again there might be several values in the primary key)

- Access class of key attributes must be the same or dominated by the non-key attributes.

-

Null integrity

- Null attribute value has same class as the key, same as before

- Null value can be overwritten and subsumed (no duplicate tuple is generated) independent of the access class of the non-null value.

- MVD not required.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy