Secure Computer Systems

Virtualization and Security

5 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Virtualization and Security

Why Virtualization

Virtualization allows users to work with virtual resources, which are easier to use than physical resources.

It also helps us achieve complete mediation. The virtual resources are mapped to physical resources by the TCB, so no physical resources are accessed without passing through the TCB. In the last module we talked about how the translation from logical addresses to physical memory achieves complete mediation.

With a virtual machine monitor (VMM or hypervisor) we virtualize all resources of the physical machine and make these virtual resources available to a guest operating system. The guest operating system does the resource management but the virtual machine monitor takes care of the resource allocation.

Because the guest operating system takes care of the resource management, our system is less complex. Less complexity gives us more confidence that our system achieves correctness (economy of mechanism).

Type 1 vs. Type 2 VMM

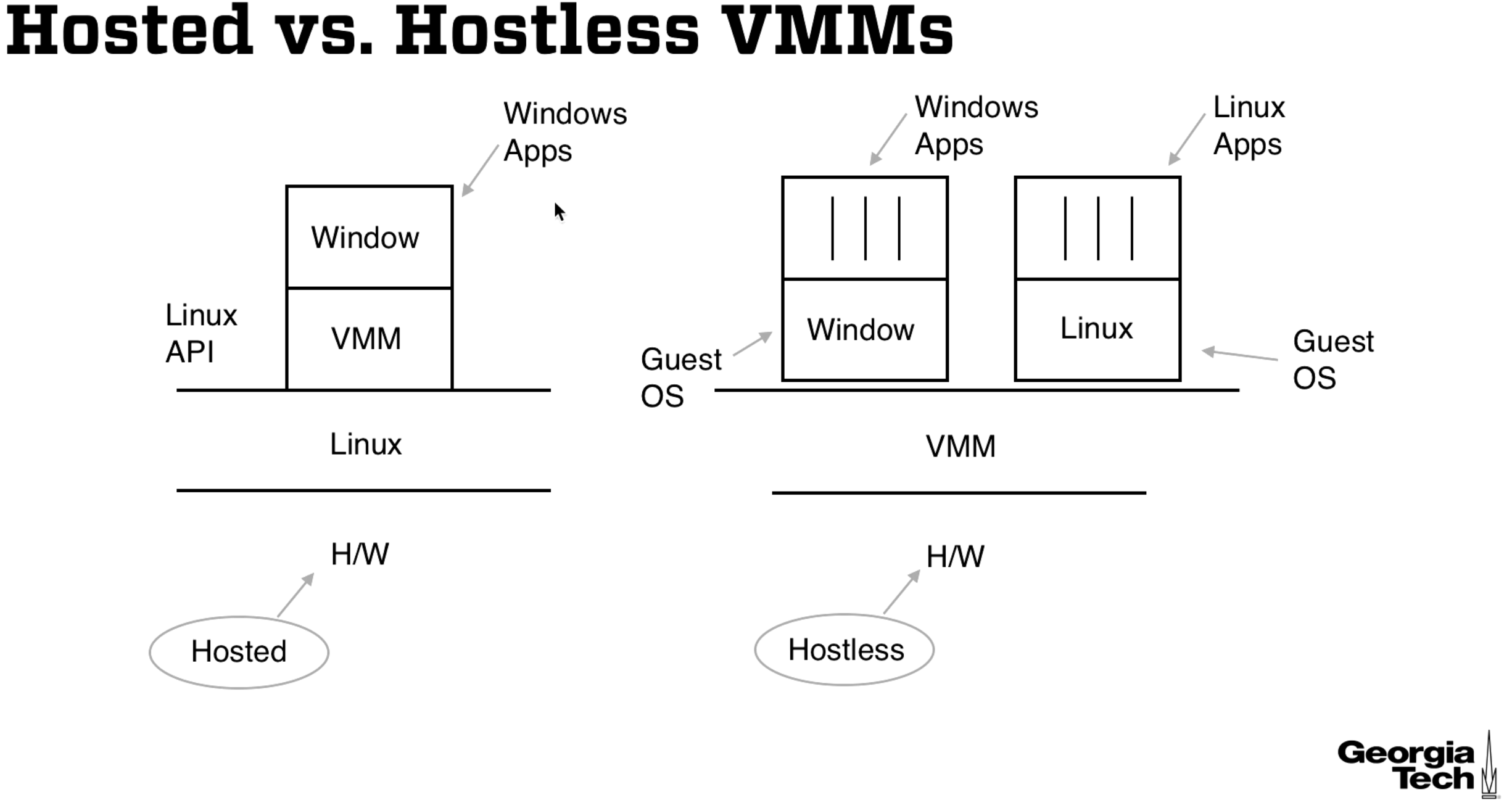

On the left of the below diagram we have a hosted VMM (type 2) and on the right we have a hostless VMM (type 1).

For the hosted VMM we have a virtual machine (like Virtualbox) that lets us run Windows on a Linux operating system.

For the hostless VMM we have the operating systems on top of the VMM.

Our focus throughout this module is on hostless VMMs.

System Calls Revisited

If there is no VMM then system calls are sent from a process to the operating system. If there is a VMM then the system call first gets sent to the VMM (has the highest privileges) and then is sent to the guest OS (lower privileges than VMM).

Hostless VMM is the TCB

Hostless VMM's are smaller and more likely to be correct because the guest OS manages resources. Some popular hostless VMMs include -

- Xen

- VMWare ESx

- Hyper V

- KVM

Green vs. Red VMs

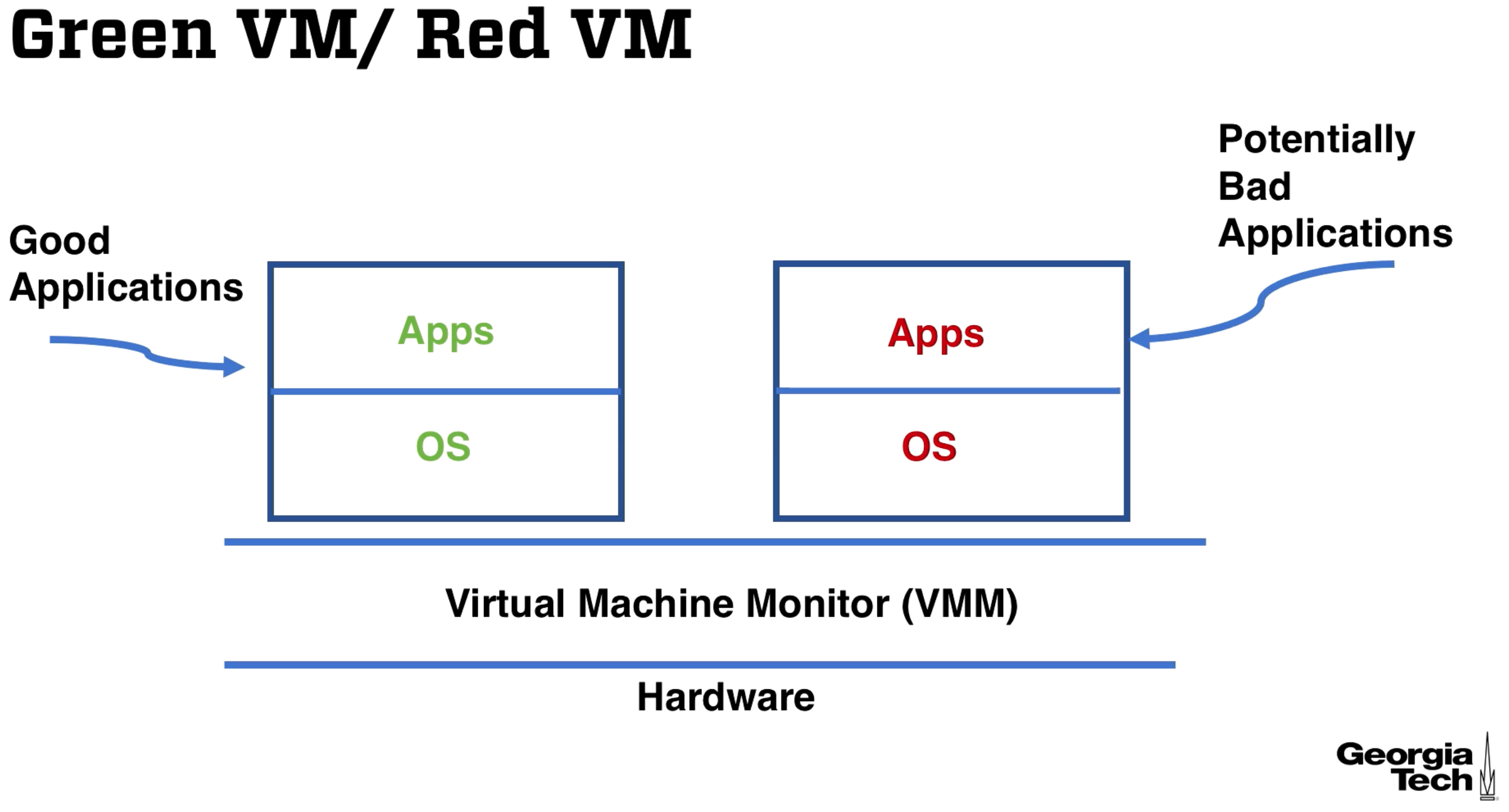

The green VM has applications that you trust running on an OS that you trust, and has sensitive data to protect.

If you want to run a potentially unsafe application you can run it in the red VM, and if you trust the VMM, the green VMM is isolated from the red VM.

- Green VMs are not affected by the exploitation of a red VM.

- If the VMM is compromised then the green VM is compromised.

- Within the green VM the guest operating system separates applications from each other. An application must trust the VM guest OS as well as the VMM.

- VMMs give us another layer of protection from harmful applications.

VMM Requirements

- Transparency - The VMM provides an identical execution environment to the underlying physical machine. Note: There will be some performance degradation.

- Complete Mediation - VMM controls all physical resources

- Efficiency - Most VM instructions should execute natively (directly on the hardware).

Requirements for Type 1

Non-privileged instructions are executed in the same way for user code, the guest OS VM, and the VMM. Privileged instructions executed outside the VMM must trap to the VMM.

Examples of privileged instructions:

- Instructions that impact memory protection system and address translation.

- Instructions that read or write into sensitive registers and memory locations.

- Instructions that attempt to reference mode of VM and state of physical machine.

Some older hardware like the Intel Pentium simply couldn't be virtualized because of sensitive instructions that were not privileged. This led to the introduction of Virtualization technology (VT-x).

Paravirtualization vs. Virtualization

With virtualization the VMM must be the most privileged. This means that it is running in ring 0. But the OS wants to run in ring 0!

Something has to change so that the OS can run while the VMM is in ring 0. Earlier we said that transparency is a requirement of the VMM, meaning that the execution environment is identical. If we make modifications to the OS to resolve the ring 0 dilemma, we have changed the execution environment, failing to meet the requirements of the VMM.

This leads to the idea of paravirtualization. We make the necessary changes, and now we call it paravirtualization instead of virtualization.

Hardware Support for Virtualization

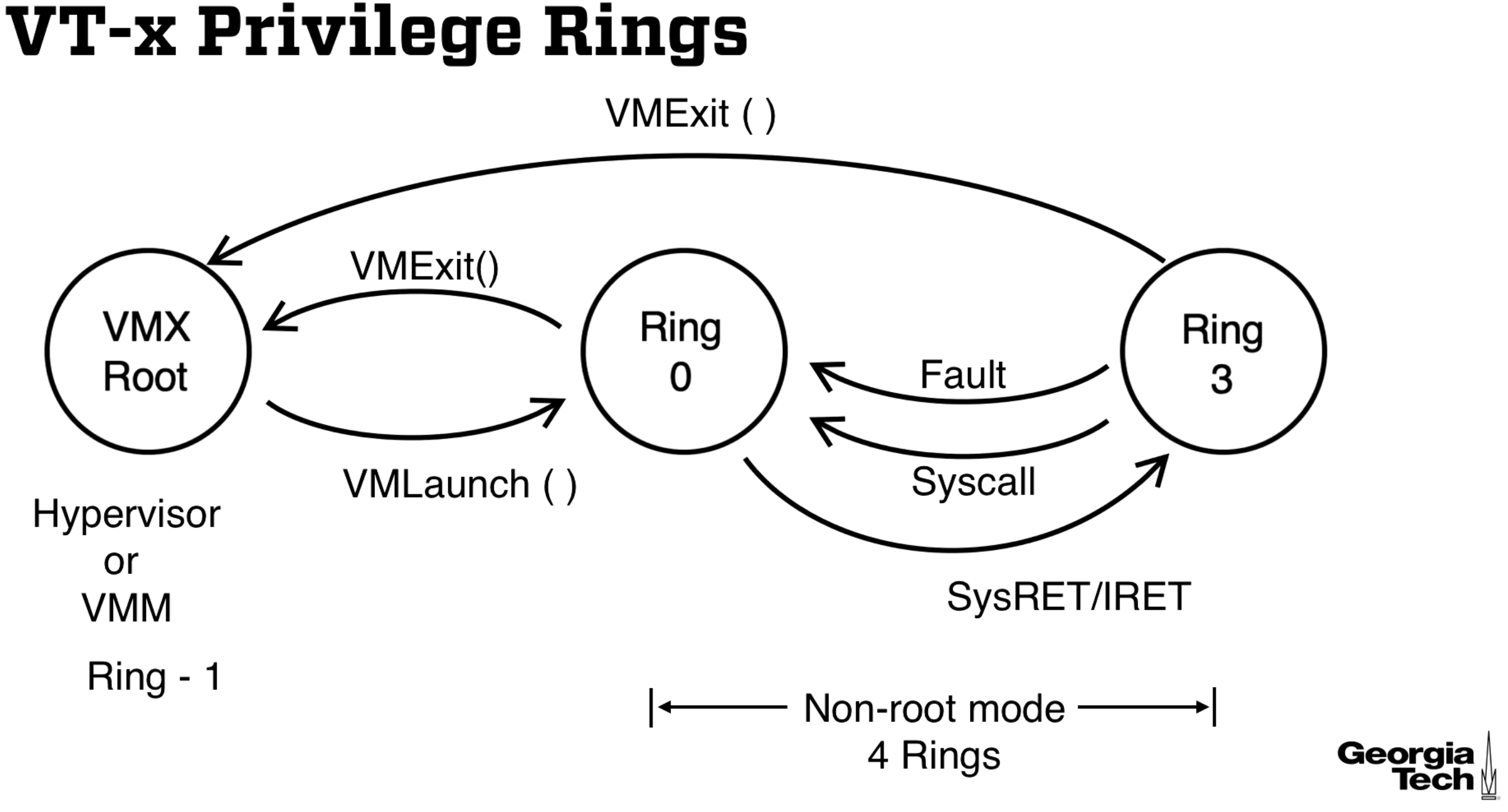

Intel introduces two modes, each having four rings (0-3). VMX root is for the VMM and VMX non-root is for the OS so that it can run in ring 0.

The VMX non-root will restrict access to some registers and privileged instructions even when the guest OS is in ring 0. Some new instructions were added for root mode as well.

Control is transferred from VMM to VM via VMEntry (which is called from VMLaunch in the below diagram) and from the VM to the VMM via VMExit. Although VMX Root has 4 rings, it only uses ring 0, which we call -1. Confusing, right? The OS gets to have a proper ring 0 and no modifications are necessary, allowing for full virtualization.

Address Translation in VT-x

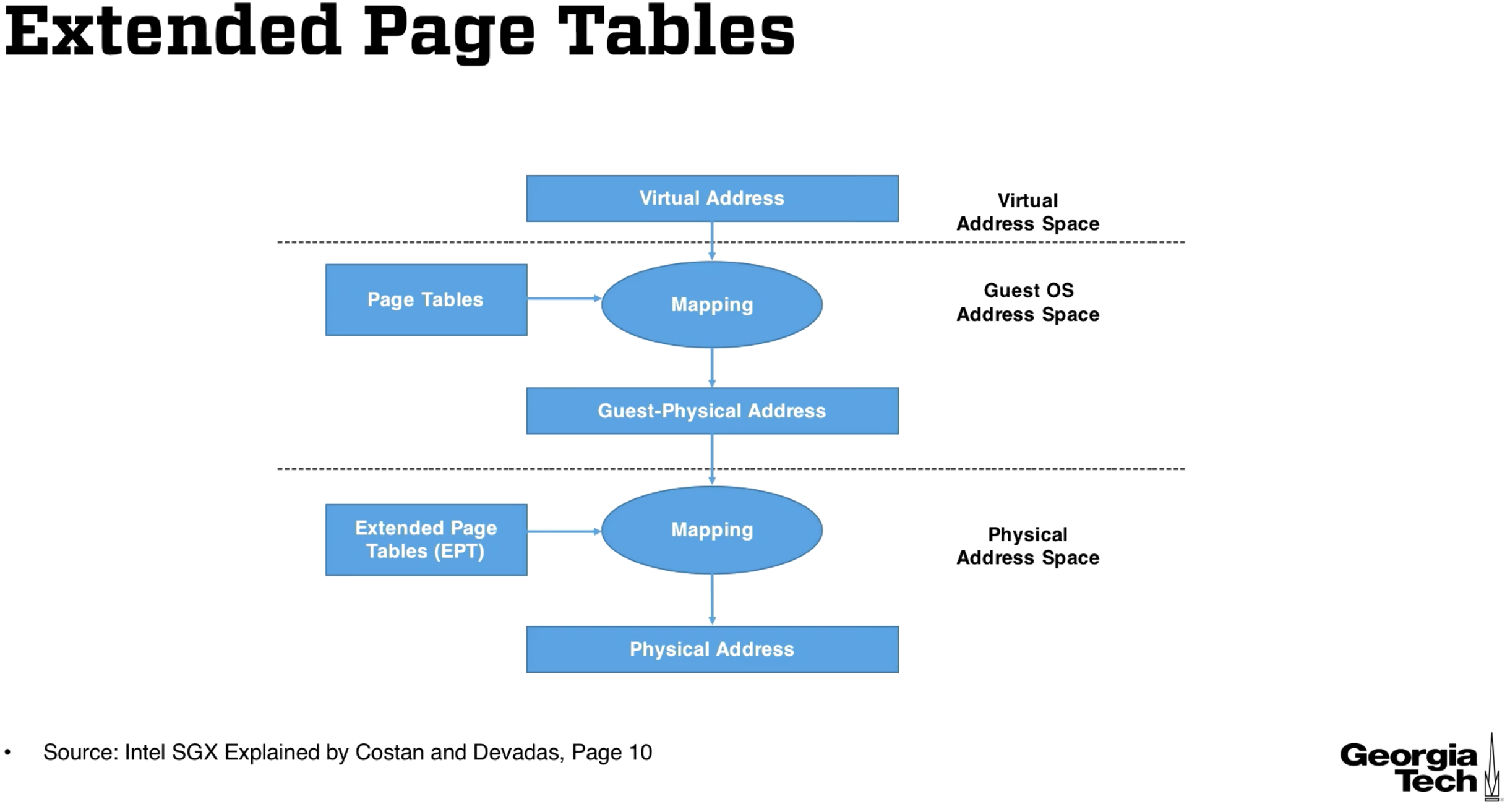

The OS likes to manage the logical to physical address mappings, but in this case the OS is a guest OS and it does not have control of physical memory.

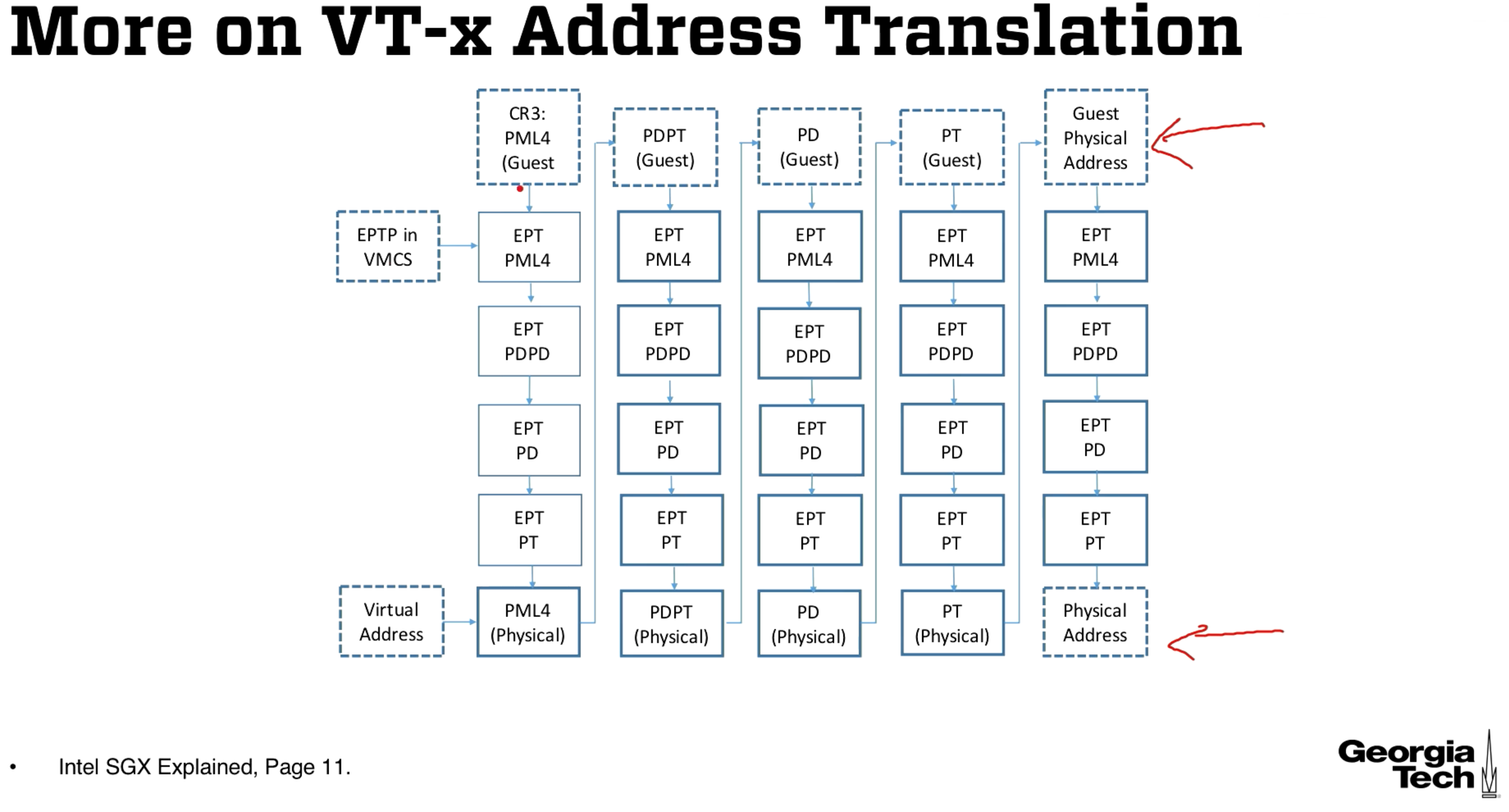

We solve this by adding a layer of indirection. The OS will instead map to a guest-physical address in guest-physical address space. The VMM maps the guest physical adddresses to the physical addresses with a paging structure called extended page tables (EPT). Here's a diagram -

The columns are last module's mapping from logical to physical addresses in 64 bit architectures. So are the top and bottom rows. Basically whenever we want to get an address for the next stage in the translation process, we must get this address from the physical memory and go through the extended page table's translation process.

Miscellaneous

SGX

If you don't trust the VMM, Intel produced Software Guard Extensions (SGX). SGX lets you make a region of addresses into an enclave which is protected from the VMM, guest OS, and applications outside of the enclave.

Attacks Against Virtualization Systems

The VMM is less complex and less prone to attacks, but is not immune to attacks. You can see this in the National Vulnerability Database.

Xen

Xen VMM has a VM that controls other VMs called dom 0. This VM is part of the TCB, but isn't doing anything like running user applications.

Malware Analysis

You might use virtualization to set up a test environment for determining if an untrusted application is malware. The malware might try to evade detection by only running if it thinks it is not on a virtual machine. If our VMM achieves total transparency then the virus cannot tell it is on a VM.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy