Operating Systems

Synchronization Constructs

21 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Synchronization Constructs

Why Are We Still Talking About Synchronization?

During our past discussion of synchronization constructs - like mutexes and condition variables - we mentioned a number of common pitfalls.

We covered issues related to correctness and ease-of-use. For example, we talked about how easy it is to unlock the wrong mutex or signal on the wrong condition variable. The use of mutexes and condition variables is not an error proof process.

When we discussed the readers/writer problem, we had to introduce a proxy variable to encapsulate the various states of our application. We needed this helper variable because mutexes by themselves can only represent simply binary states: they lack expressive power. We cannot express arbitrary synchronization conditions using the constructs we have seen already.

Synchronization constructs require low level support from the hardware in order to guarantee the correctness of the synchronization construct. Hardware provides this type of low level support via atomic instructions.

Our discussions will cover alternative synchronization constructs that can help solve some of the issues we experienced with mutexes and condition variables as well as examine how different types of hardware achieve efficient implementations of the synchronization constructs.

Spinlocks

One of the most basic synchronization constructs is the spinlock.

In some ways spinlocks are like mutexes. For example, a spinlock is used to provide mutual exclusion, and it has certain constructs that are similar to the mutex lock/unlock operations.

However, spinlocks are different from mutexes in an important way.

When a spinlock is locked, and a thread is attempting to lock it, that thread is not blocked. Instead, the thread is spinning. It is running on the CPU and repeatedly checking to see if the lock has become free. With mutexes, the thread attempting to lock the mutex would have relinquished the CPU and allowed another thread to run. With spinlocks, the thread will burn CPU cycles until the lock becomes free or until the thread becomes preempted for some reason.

Because of their simplicity, spinlocks are a basic synchronization primitive that can be used to implement more complicated synchronization constructs.

Semaphores

As a synchronization construct, semaphores allow us to express count related synchronization requirements.

Semaphores are initialized with an integer value. Threads arriving at a semaphore with a nonzero value will decrement the value and proceed with their execution. Threads arriving at a semaphore with a zero value will have to wait. As a result, the number of threads that will be allowed to proceed at a given time will equal the initialization value of the semaphore.

When a thread leaves the critical section, it signals the semaphore, which will increment the semaphore's counter.

If a semaphore is initialized with a 1 - a binary semaphore - it will behave like a mutex, only allowing one thread at a time to pass.

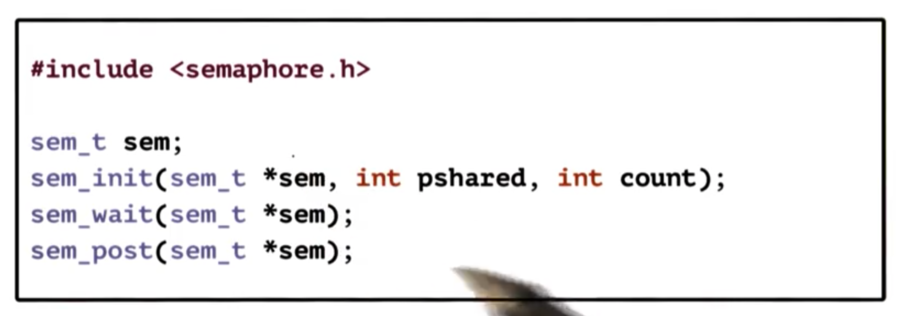

POSIX Semaphores

The simple POSIX semaphore API defines one type sem_t as well as three operations that manipulate that type. These operations create the semaphore, wait on the semaphore, and unlock the semaphore.

NB The pshared flag indicates whether the semaphore is to be shared across processes.

Reader/Writer Locks

When specifying synchronization requirements, it is sometimes useful to distinguish among different types of resource access.

For instance, we commonly want to distinguish "read" accesses - those that do not modify a shared resource - from "write" accesses - those that do modify a shared resource. For read accesses, a resource can be shared concurrently while write accesses requires exclusive access to a resource.

This is a common scenario and, as a result, many operating systems and language runtimes support a construct known as reader/writer locks.

A reader/writer lock behaves similarly to a mutex; however, now the developer only has to specify the type of access that they wish to perform - read vs. write - and the lock takes care of access control behind the scenes.

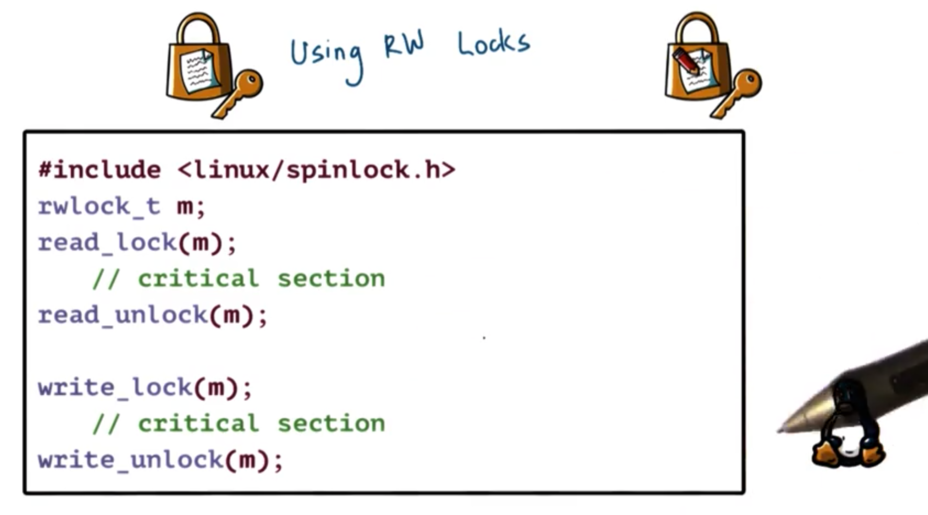

Using Reader/Writer Locks

Here is the primary API for reader/writer locks in Linux.

As usual, we have a datatype - rwlock_t and we perform operations on that data type. We can lock/unlock the lock for reads as well as for writes.

Reader/writer locks are supported in many operating systems and language runtimes.

However, the semantics may be different across different environments.

Some implementations refer to reader/writer locks as shared/exclusive locks.

Implementations may differ on how recursively-obtained read locks are unlocked. When unlocking a recursive read lock, some implementations unlock all the recursive locks, while others only unlock the most recently acquired lock.

Some implementations allow readers to convert their lock into a writer lock mid-execution, while other implementations do not allow this upgrade.

Some implementations block an incoming reader if there is a writer already waiting, while others will let this reader acquire its lock.

Monitors

All of the constructs that we have seen so far require developers to explicitly invoke the lock/unlock and wait/signal operations. As we have seen, this introduces more opportunity to make errors.

Monitors are a higher level synchronization construct that allow us to avoid manually invoking these synchronization operations. A monitor will specify a shared resource, the entry procedures for accessing that resource, and potential condition variables used to wake up different types of waiting threads.

When invoking the entry procedure, all of the necessary locking and checking will take place by the monitor behind the scenes. When a thread is done with a shared resource and is exiting the procedure, all of the unlocking and potential signaling is again performed by the monitor behind the scenes.

More Synchronization Constructs

Serializers make it easier to define priorities and also hide the need for explicit signaling and explicit use of condition variables from the programmer.

Path Expressions require that a programmer specify a regular expression that captures the correct synchronization behavior. As opposed to using locks, the programmer would specify something like "Many Reads, Single Write", and the runtime will make sure that the way the operations are interleaved satisfies the regular expression.

Barriers are like reverse semaphores. While a semaphore allows n threads to proceed before it blocks, a barrier blocks until n threads arrive at the barrier point. Similarly, Rendezvous Points also wait for multiple threads to arrive at a particular point in execution.

To further boost scalability and efficiency metrics, there are efforts to achieve concurrency without explicitly locking and waiting. These wait-free synchronization constructs are optimistic in the sense that they bet on the fact that there won't be any concurrent writes and that it is safe to allow reads to proceed concurrently. An example of this is read-copy-update (RCU) lock that is part of the Linux kernel.

All of these methods require some support from the underlying hardware to atomically make updates to a memory location. This is the only way they can actually guarantee that a lock is properly acquired and that protected state changes are performed in a safe, race-free way.

Sync Building Block Spinlock

We will now focus on "The Performance of Spin Lock Alternatives for Shared Memory Multiprocessors", a paper that discusses different implementations of spinlocks. Since spinlocks are one of the most basic synchronization primitives and are used to create more complex synchronization constructs, this paper will help us understand both spinlocks and their higher level counterparts.

Need for Hardware Support

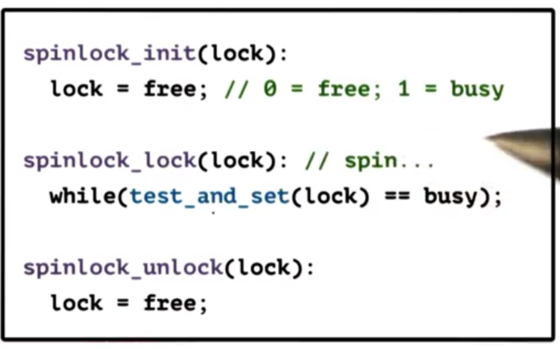

We need the checking of the lock value and the setting of the lock value to happen atomically, so that we can guarantee that only one thread at a time can successfully obtain the lock.

Here is the current implementation of a spinlock locking operation that does not work.

spinlock_lock(lock) {

while(lock == busy)

// Spin

lock = busy;

}The problem with this implementation is that it takes multiple cycles to perform the check and the set and during these cycles threads can be interleaved in arbitrary ways.

To make this work, we have to rely on hardware-supported atomic instructions.

Atomic Instructions

Each type of hardware will support a number of atomic instructions. Some examples include

test_and_setread_and_incrementcompare_and_swap

Each of these operations performs some multi step, multi cycle operation. Because they are atomic instructions, however, the hardware makes some guarantees. First, these operations will happen atomically; that is, completely or not at all. In addition, the hardware guarantees mutual exclusion - threads on multiple cores cannot perform the atomic operations in parallel. All concurrent attempts to execute an instruction will be queued and performed serially.

Here is a new implementation for a spinlock locking operation which uses an atomic instruction.

spinlock_lock(lock) {

while(test_and_set(lock) == busy);

}When the first thread arrives, test_and_set looks at the value that lock points to. This value will initially be zero. test_and_set atomically sets the value to one, and returns zero. busy is equal to one. Thus, the first thread can proceed. When subsequent threads arrive, test_and_set will look at the value - which is set - and just return it. These threads will spin.

Which specific atomic instructions are available on a given platform varies from hardware to hardware. There may be differences in the efficiencies with which different atomic operations execute on different architectures. For this reason, software built with specific atomic instructions needs to be ported; that is, we need to make sure the implementation uses one of the atomic instructions available on the target platform. We also have to make sure that the software is optimized so that it uses the most efficient atomics on a target platform and uses them in an efficient way.

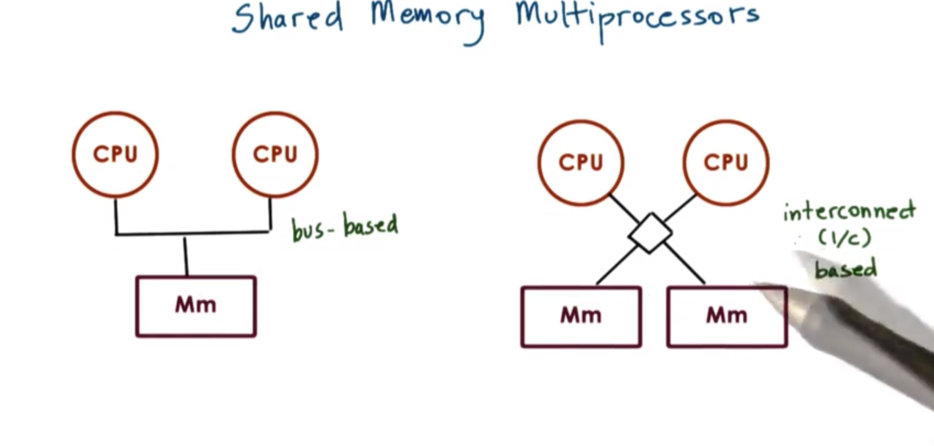

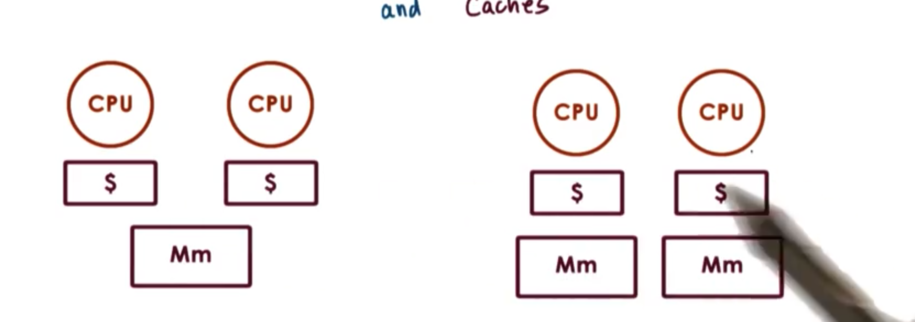

Shared Memory Multiprocessors

A multiprocessor system consists of more than one CPU and some memory unit that is accessible to all of these CPUs. That is, the memory component is shared by the CPUs.

In the interconnect-based configuration, multiple memory references can be in flight at a given moment, one to each connected memory module. In a bus-based configuration, the shared bus can only support one memory reference at a time.

Shared memory multiprocessors are also referred to as symmetric multiprocessors, or just SMPs.

Each of the CPUs in an SMP platform will have a cache.

In general, access to the cache data is faster than access to data in main memory. Put another way, caches hide memory latency. This latency is even more pronounced in shared memory systems because there may be contention amongst different CPUs for the shared memory components. This contention will cause memory accesses to be delayed, making cached lookups appear that much faster.

When CPUs perform a write, many things can happen.

For example, we may not even allow a CPU to write to its cache. A write will go directly to main memory, and any cache references will be invalidated. This is called no-write.

As one alternative, the CPU write may be applied both to the cache and in memory. This is called write-through.

A final alternative is to apply the write immediately to the cache, and perform the write in main memory at some later point in time, perhaps when the cache entry is evicted. This is called write-back.

Cache Coherence

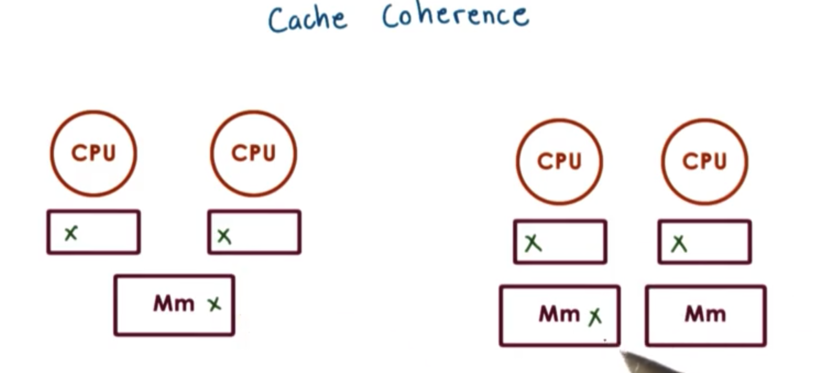

What happens when multiple CPUs reference the same data?

On some architectures this problem needs to be dealt with completely in software; otherwise, the caches will be incoherent. For instance, if one CPU writes a new version of X to its cache, the hardware will not update the value across the other CPU caches. These architectures are called non-cache-coherent (NCC) architectures.

On cache-coherent (CC) architectures, the hardware will take care of all of the necessary steps to ensure that the caches are coherent. If one CPU writes a new version of X to its cache, the hardware will step in and ensure that the value is updated across CPU caches.

There are two basic strategies by which the hardware can achieve cache coherence.

Hardware using the write-invalidate (WI) strategy will invalidate all cache entries of X once one CPU updates its copy of X. Future references to invalidated cache entries will have to pass through to main memory before being re-cached.

Hardware using the write-update (WU) strategy will ensure that all cache entries of X are updated once one CPU updates its copy of X. Subsequent accesses of X by any of the CPUs will continue to be served by the cache.

With write-invalidate, we pose lower bandwidth requirements on the shared interconnect in the system. This is because we don't have to send the value of X, but rather just its address so it can be invalidated amongst the other caches. Once a cache invalidation occurs, subsequent changes to X won't require subsequent invalidations: a cache either has an entry for X or it doesn't.

If X isn't needed on any of the other CPUs anytime soon, its possible to amortize the cost of the coherence traffic over multiple changes. X can change multiple times on one CPU before its value is needed on another CPU.

For write-update architectures, the benefit is that the X will be available immediately on the other CPUs that need to access it. We will not have to pay the cost of a main memory access. Programs that will need to access the new value ofX immediately on another CPU will benefit from this design.

The use of write-update or write-invalidate is determined by the hardware supporting your platform. You as the software developer have no say in which strategy is used.

Cache Coherence and Atomics

Let's consider a scenario in which we have two CPUs. Each CPU needs to perform an atomic operation concerning X, and both CPUs have a reference to X present in their caches.

When an atomic instruction is performed against the cached value of X on one CPU, it is really challenging to know whether or not an atomic instruction will be attempted on the cached value of X on another CPU. We obviously cannot have incoherent cache references between CPUs: this will affect the correctness of our applications.

Atomic operations always bypass the caches and are issued directly to the memory location where the particular target variable is stored.

By forcing atomic operations to go directly to the memory controller, we enforce a central entry point where all of the references can be ordered and synchronized in a unique manner. None of the race conditions that could have occurred had we let atomic update the cache can occur now.

That being said, atomic instructions will take much longer than other types of instructions, since they can never leverage the cache. Not only will they always have to access main memory, but they will also have to contend on that memory.

In addition, in order to guarantee atomic behavior, we have to generate the coherence traffic to either update or invalidate all of the cached references to X, regardless of whether X changed. This is a decision that was made to err on the side of safety.

In summary, atomic instructions on SMP systems are more expensive than on single CPU system because of bus or I/C contention. In addition, atomics in general are more expensive because they bypass the cache and always trigger coherence traffic.

Spinlock Performance Metrics

We want the spinlock to have low latency. We can define latency as the time it takes a thread to acquire a free lock. Ideally, we want the thread to be able to acquire a free lock immediately with a single atomic instruction.

In addition, we want the spinlock to have low delay/waiting time. We can define delay as the amount of time required for a thread to stop spinning and acquire a lock that has been freed. Again, we ideally would want the thread to be able to stop spinning and acquire a free lock immediately.

Finally, we would like a design that reduces contention on the shared bus or interconnect. By contention, we mean the contention due to the actual atomic memory references as well as the subsequent coherence traffic. Contention is bad because it will delay any other CPU that is trying to access memory. Most pertinent to our use case though, contention will also delay the acquisition and release of the spinlock.

Test and Set Spinlock

Here is the API for the test-and-set spinlock.

The test_and_set instruction is a very common atomic that most hardware platforms support.

From a latency perspective, this spinlock is as good as it gets. We only execute one atomic operation, and there is no way we can do better than this.

Regarding delay, this implementation could perform well. We are continuously just spinning on the atomic. As soon as the lock becomes free, the very next call to test_and_set - which is the very next instruction, given that we are spinning on the atomic - will immediately detect that, and the thread will acquire the lock and exit the loop.

From a contention perspective this lock does not perform well. As long as the threads are spinning on the test_and_set instruction, the processor has to continuously go to main memory on each instruction. This will delay all other CPUs that need to access memory.

The real problem with this implementation is that we are continuously spinning on the atomic instruction. Regardless of cache coherence, we are forced to constantly waste time going to memory every time we execute the test_and_set instruction.

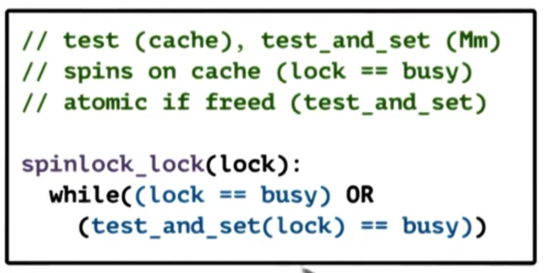

Test and Test and Set Spinlock

The problem with the previous implementation is that all of the CPUs are spinning on the atomic operation. Let's try to separate the test part - checking the value of the lock - from the atomic.

The intuition is that CPUs can potentially test their cached copy of the lock and only execute the atomic if it detects that its cached copy has changed.

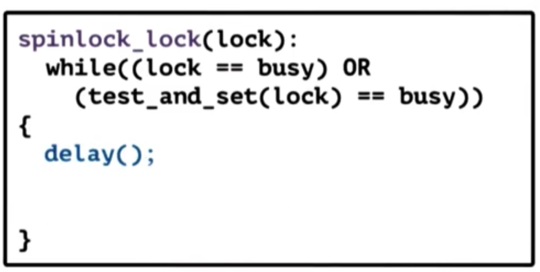

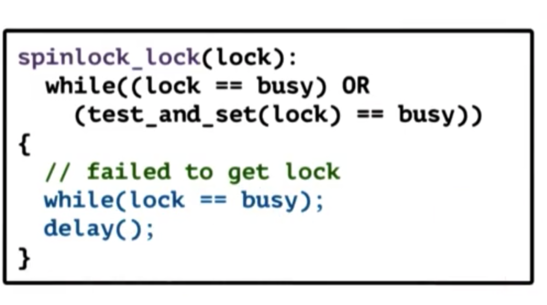

Here is the resulting spinlock lock operation.

First we check if the lock is busy. Importantly, this check is performed against the cached value. As long as the lock is busy, we will stay in the while loop, and we won't need to evaluate the second part of the predicate. Only when the lock becomes free - when lock == busy evaluates to false - do we actually execute the atomic.

This spinlock is referred to as the test-and-test-and-set spinlock. It is also called a spin-on-read or spin-on-cached-value spinlock.

From a latency and delay standpoint, this lock is okay. It is slightly worse than the test-and-set lock because we do have to perform this extra step.

From a contention standpoint, our performance varies.

If we don't have a cache coherent architecture, there is no difference in contention. Every single memory reference will go to memory.

If we have cache coherence with the write-update strategy, our contention improves. The only problem with write-update is that all of the processors will see the value of the lock as free and thus all of them will try to lock the lock at once.

If we have cache coherence with the write-invalidate strategy, our contention is terrible. Every single attempt to acquire the lock will generate contention for the memory module and will also create invalidation traffic.

One outcome of executing an atomic instruction is that we will trigger the cache coherence strategy regardless of whether or not the value protected by the atomic changes.

If we have a write-update situation, that coherence traffic will update the value of the other caches with the new value of the lock. If the lock was busy before the write-update event, and the lock remains busy after the write-update event, there is no problem. The CPU can keep spinning on the cached copy.

However, write-invalidate will invalidate the cached copy. Even if the value hasn't changed, the invalidation will force the CPU to go to main memory to execute the atomic. What this means is that any time another CPU executes an atomic, all of the other CPUs will be invalidated and will have to go to memory.

Spinlock "Delay" Alternatives

We can introduce a delay in order to deal with the problems introduced by the test_and_set and test_and_test_and_set spin locks.

This implementation introduces a delay every time the thread notices that the lock is free.

The rationale behind this is to prevent every thread from executing the atomic instruction at the same time.

As a result, the contention in the system will be significantly improved. When the delay expires, the delayed threads will try to re-check the value of the lock, and it's possible that another thread executed the atomic and the delayed threads will see that the lock is busy. If the lock is free, the delayed thread will execute the atomic.

There will be fewer cases in which threads see a busy lock as free and try to execute an atomic that will not be successful.

From a latency perspective, this lock is okay. We still have to perform a memory reference to bring the lock into the cache, and then another to perform the atomic. However, this is not much different from what we have seen in the past.

From a delay perspective, clearly our performance has decreased. Once a thread sees that a lock is free, we have to delay for some (seemingly arbitrary) amount of time. If there is no contention for the lock that delay is wasted time.

An alternative delay-based lock introduces a delay after each memory reference.

The main benefit of this is that it works on NCC architectures. Since a thread has to go to main memory on every reference on NCC architectures, introducing an artificial delay great decreases the number of reference the thread has to perform while spinning.

Unfortunately, this alternative will hurt the delay much more, because the thread will delay every time the lock is referenced, not just when the thread detects the lock has become free.

Picking a Delay

One strategy is to pick a static delay, which is based on some fixed information, such as the CPU ID where the process is running.

One benefit of this approach is its simplicity, and the fact that under high load static delays will likely spread out all of the atomic references such that there is little or no contention.

The problem with this approach is that it will create unnecessary load under low contention. For example, if one process is running on a CPU with an ID of 1, and another process is running on a CPU with an ID of 32, and the delay calculation is 100ms * CPU ID, the second thread will have to wait an inordinate amount of time before executing, even though there is no contention.

To avoid the issue of excessive delays without contention, dynamic delays can be used. With dynamic delays, each thread will take a random delay value from a range of possible delays that increases with the "perceived" contention in the system.

Under high load, both dynamic and static delays will be sufficient enough to reduce contention within the system.

How can we evaluate how much contention there is in the system?

A good metric to estimate the contention is to track the number of failed test_and_set operations. The more these operations fail, the more likely it is that there is a higher degree of contention.

If we delay after each lock reference, however, our delay grows not only as a function of contention but also as a function of the the length of the critical section. If a thread is executing a large critical section, all spinning threads will be increasing their delays even though the contention in the system hasn't actually increased.

Queueing Lock

The reason for introducing a delay is to guard against the case where every thread tries to acquire a lock once it is freed.

Alternatively, if we can prevent every thread from seeing that the lock has been freed at the same time, we can indirectly prevent the case of all threads rushing to acquire the lock simultaneously.

The lock that controls which thread(s) see that the lock is free at which time is the queuing lock.

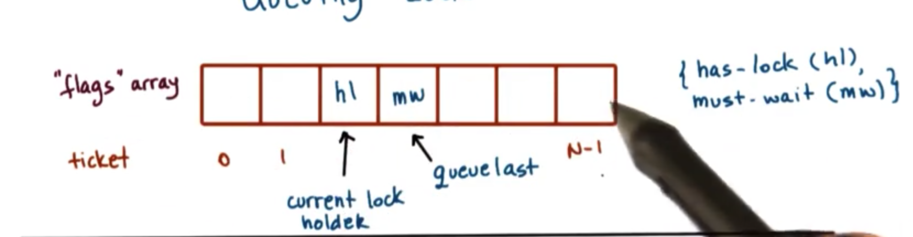

The queueing lock uses an array of flags with up to n elements, where n is the number of threads in the system. Each element in the array will have one of two values: either has_lock or must_wait. In addition, one pointer will indicate the current lock holder (which will have a value of has_lock), and another pointer will reference the last element on the queue.

When a new thread arrives at the lock, it will receive a ticket, which corresponds to the current position of the thread in the lock. This will be done by adding it after the existing last element in the queue.

Since multiple threads may enter the lock at the same time, it's important to increment the queuelast pointer atomically. This requires some support for a read_and_incremement atomic.

For each thread arriving at the lock, the assigned element of the flags array at the ticket index acts like a private lock. As long as this value is must_wait, the thread will have to spin. When the value of the element is becomes has_lock, this will signify to the threads that the lock is free and they can attempt to enter their critical section.

When a thread completes a critical section and needs to release the lock, it needs to signal the next thread. Thus queue[ticket + 1] = has_lock.

This strategy has two drawbacks. First, it requires support for the read_and_increment atomic, which is less common that test_and_set.

In addition, this lock requires much more space than other locks. All other locks required a single memory location to track the value of the lock. This lock requires n such locations, one for each thread.

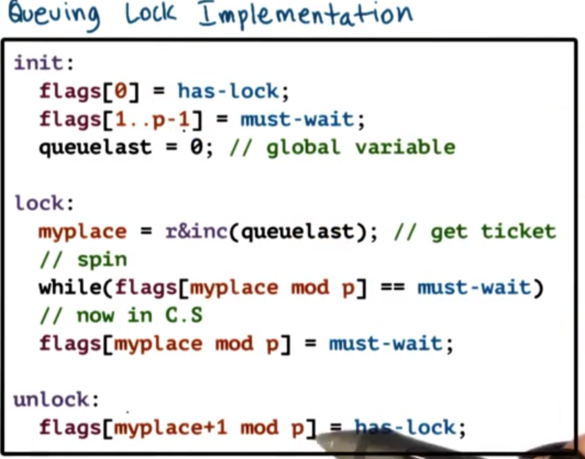

Queueing Lock Implementation

The atomic operation involves the variable queuelast, but the rest of the locking code doesn't involve that variable. Any invalidation traffic concerned with cached values of queuelock aren't going to concern the spinning that occurs on any of the elements in the flags array.

From a latency perspective, this lock is not very efficient. It performs a more complex atomic operation, read_and_increment which takes more cycles than a standard test_and_set.

From a delay perspective, this lock is good. Each lock holder directly signals the next element in the queue that the lock has been freed.

From a contention perspective, this lock is much better than any locks we have discussed, since the atomic is only executed once up front and is not part of the spinning code. The atomic operation and the spinning code involve separate variables, so cache invalidation on the atomic variable doesn't impact spinning.

In order to realize these contention gains, we must have a cache coherent architecture. Otherwise, spinning must involve remote memory references. In addition, we have to make sure that every element is on a different cache line. Otherwise, when we change the value of one element in the array, we will invalidate the entire cache line, so the processors spinning on other elements will have their caches invalidated.

Spinlock Performance Comparisons

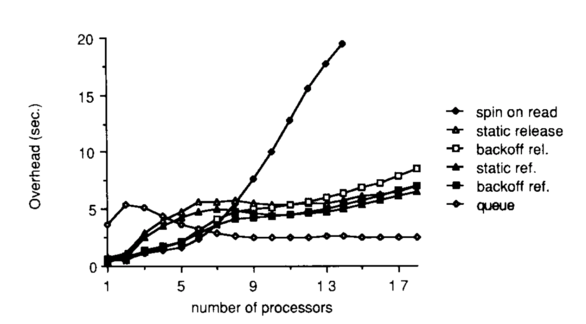

This figures shows measurements that were gathered from executing a program that had multiple processes. Each process executed a critical section in a loop, one million times. The number of processes in the system was varied such that there was only one process per processor.

The platform that was used was Sequent Symmetry, which has twenty processors, which explains why the number of processors on the graph is capped at 20. This platform is cache coherent with write-invalidate.

The metric that was computed was the overhead, which was measured in comparison to a case of ideal performance, which corresponded to the theoretical limit - assuming no delay or contention - of how long it would take to execute the number of critical sections. The measured difference between the theoretical limit and the observed execution time was the overhead.

Under high load, the queueing lock performs the best. It is the most scalable; as we add more processors, the overhead does not increase.

The test_and_test_and_set lock performs the worst under load. The platform is cache coherent with write-invalidate, and we discussed earlier how this strategy forces O(N^2) memory references to maintain cache coherence.

Of the delay-based alternatives, the static locks are a little better than the dynamic locks, since dynamic locks have some measure of randomness and will have more collisions than static locks. Also, delaying after every reference is slightly better than delaying after every lock release.

Under smaller loads, test_and_test_and_set performs pretty well: it has low latency. We can also see that the dynamic delay alternatives perform better than the static ones. Static delay locks can naively enforce unnecessarily large delays under small loads, while dynamic alternatives adjust based on contention.

Under light loads, the queueing lock performs the worst. This is because of the higher latency inherent to the queueing lock, in the form of the more complex atomic, read_and_increment, as well as some additional computation that is required at lock time.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy