Operating Systems

Distributed Shared Memory

18 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Distributed Shared Memory

Reviewing DFS

Distributed file systems are an example of a distributed service in which the state - the files - are stored on some set of server nodes and are then accessed by some set of client nodes. The servers own and manage the state, and provide a service - the file access operations - which are requested by the clients and operate on the state.

The primary focus of the DFS lesson was the caching mechanisms, which were useful to improve performance as seen by clients and scalability as supported by the servers.

We didn't talk about how the multiple file servers share and coordinate the application state amongst themselves. We also didn't talk about the scenario in which all of the nodes in the system were both servers and clients (peers).

Peer Distributed Applications

Often it is hard to distinguish between servers and clients in a system. The state of an application can be shared across all nodes, with different nodes both requesting and serving state at different points in times.

Every node in the system owns some portion of the state. There is some state that is locally stored on a particular node. The overall application state is the union of all of the pieces of state that are present on any one node.

All of the nodes are peers: they all require accesses to the state located elsewhere in the system and provide accesses to their local state.

This is slightly different from "peer-to-peer" applications: it's likely that there will still be some nodes that provide some overall configuration or management of the entire system. In a peer-to-peer system, these tasks would still be performed cooperatively by all peers.

Distributed Shared Memory (DSM)

Distributed shared memory is a service that manages memory across multiple nodes so that applications will have the illusion that they are running on a single shared-memory machine.

Each node in the system owns some portion of the physical memory, and provides the operations - reads and writes - on that memory. The reads and writes may originate from any of the nodes in the system.

Each node needs to be involved in some consistency protocols to ensure that shared accesses to the state have meaningful semantics.

For instance, when nodes read and write shared memory locations, these reads and writes must be ordered and observed by the remaining nodes in the system in consistent ways.

Distributed shared memory mechanisms are important to study because they permit scaling beyond the limitations of how much memory we can include in a single machine.

Single machines with large amounts of memory can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per machine. In order to scale up memory affordably, it's imperative to understand DSM concepts and semantics so many cheap machines can be connected to give the illusion of a high memory "single" machine.

Naturally, the overall memory access will be slower in a DSM environment as a result of network costs, but this is often affordable, and optimizable. It is possible to hide these network delays by making the right application design choices.

Distributed shared memory is becoming more relevant today because commodity interconnect technologies offer really low latencies between nodes in a system via Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) interfaces.

Hardware vs Software DSM

DSM can be supported in hardware or software.

Hardware-supported DSM relies on some physical interconnect. The OS running on each physical node is under the impression that it has access to much larger physical memory, and is allowed to establish virtual to physical mappings that point to physical addresses on other nodes.

Memory accesses that reference remote memory locations are passed to the network interconnect card, which translates remote memory accesses into interconnect messages that are then passed to the correct remote node.

The NICs are involved in all aspects of the memory management, access and consistency and even support some atomics.

While it's very convenient to rely on hardware to do everything, this type of hardware is typically very expensive and as a result is reserved for very high-end machines.

Instead, DSM is often realized in software. The software will have to

- detect local vs remote memory accesses

- create and send messages to the appropriate node

- accept messages from other nodes and perform the encoded memory operations

- be involved in memory sharing and consistency support

This can be done at the level of the operating system or with a programming language runtime.

DSM Design: Sharing Granularity

In SMP systems, the granularity of sharing is the cache line. The hardware tracks concurrent memory accesses at the granularity of a single cache line, and triggers the necessary coherence mechanisms if it detects that a shared cache line has been modified.

For DSM, generating coherence traffic at the granularity of the cache line will be too expensive, given that this traffic has to travel over the network and incur network cost.

Instead, we can look at larger granularities for sharing:

- variable granularity

- page granularity

- object granularity

Variables are a meaningful unit from a programmer's perspective, so maybe DSM solutions can operate at the level of variable granularity. Unfortunately, this is likely still too fine-grained. Variables are still too small and occur too frequently in an application, making it likely that we will still incur very high coherence traffic overheads.

Using something larger, like a page or object makes more sense. If the DSM system is to be integrated at the operating system level, page-based granularity makes sense since the OS doesn't understand objects. Pages are larger than variables, so it's possible to amortize the cost of remote access across these larger granularities.

With some help from a compiler, application level objects can be laid out on different pages, and then we can rely on the page-based operating system level mechanism.

Alternatively, we can have a DSM that is supported by the programming language and the runtime, where the runtime understands which objects are local and which are remote. For remote objects, the runtime will generate all of the necessary operations to communicate with the remote nodes.

In the case of object granularity, the OS doesn't need to know anything about DSM, and therefore doesn't have to be modified. That being said, the language level solution is not generalizable outside of programming languages that have this DSM support.

Once we start increasing the granularity of sharing, we have to beware of false sharing.

Consider a page that internally has two variables, x and y. A process on one node is exclusively accessing and modifying x. Similarly, a process on another node is exclusively accessing and modifying y. When x and y are on the same page, the DSM system will interpret the two write accesses as an indication of concurrent access to a shared page. This will trigger coherence mechanisms which, while logically viable, are functionally superfluous.

DSM Design: Access Algorithm

Another important design point when looking at DSM solutions is to understand what types of memory accesses the higher-level applications expect to perform.

The simplest kind of application is the single reader/single writer. For these kinds of applications, the main role of the DSM layer is to provide the application with the ability to access additional, remote memory. In this case, there are not any consistency- or sharing-related challenges that need to be supported at the DSM layer.

The more complex case is when the application needs to support multiple readers/single writer or multiple readers/multiple writers. In these cases, it's not just about how to read or write the correct physical location of memory.

With multiple writers and readers, it's important that the reads return the most recent value at a memory location. It's also important that all of the writes that are performed are correctly ordered. This is necessary so as to present a consistent view of the distributed state to all of the nodes in the system.

DSM Design: Migration vs Replication

For a DSM solution to be useful, it most provide good performance to applications. Since the core service provided by DSM solutions is access, the core performance metric to analyze is access latency.

Clearly, accessing local memory is faster than remote memory, so it's important to consider how to maximize the proportion of local memory accesses.

One way to maximize the proportion of local memory accesses is through migration. Whenever a process on another node needs to access remote state, we copy the state over to that node.

Migration makes sense in the single reader/single writer case, since only one node at a time will be accessing the state. However, moving data across nodes does incur overheads.

We should be careful about this solution, even in the single reader/single writer case. Copying over a large chunk of state just for a single read or write is a cost that cannot be amortized.

With multiple readers and multiple writers, migrating the state all over the place doesn't make any sense since the state needs to be accessed by multiple nodes at the same time.

In this case, we use replication to copy the state on multiple nodes. While this solution is more general, it requires the consistency management. We have to make sure that writes are correctly ordered and that the most recent copies of the state are propagated across nodes for up-to-date reads.

One way to control the consistency overhead is to limit the number of replicas that can exist in the system at any time, since the overhead is proportional to the number of replicas.

DSM Design: Consistency Management

Once we permit multiple copies of the same data page to be stored in multiple locations, it becomes important to think about maintaining consistency.

DSM systems are expected to behave similar to SMP systems. Remember that SMP manages consistency via two strategies:

- write-invalidate

- write-update

In write-invalidate, one processor's cached value of a variable is invalidated when another processor updates that variable. In write-update, the processor's cached variable is simply updated to reflect the new value.

These coherence operations are triggered by the shared memory support in the hardware on every single write operation. The overhead of supporting this strategy in a DSM system are too high, once network costs are considered.

One option is to push invalidation messages when data is written to. This is similar to the server-based approach that we talked about in the DFS lecture.

This approach is referred to as

- proactive

- eager

- pessimistic

Another option is for one node to poll periodically for modification information regarding certain memory regions in the system. This can be done periodically or on-demand.

This approach is referred to as

- reactive

- lazy

- optimistic

Regardless of which strategy we chose, when these methods get triggered depends on the consistency model for the shared state.

DSM Architecture

Let's look at how a DSM system can be designed.

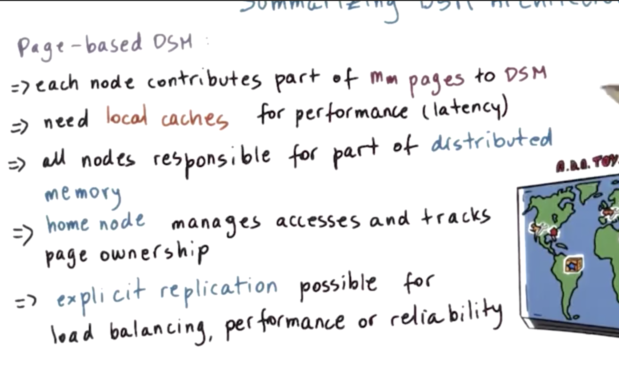

This system consists of a number of nodes, each with their own physical memory. Each node may contribute only a portion of their physical memory towards the DSM system. The rest of the memory can be used for caching, replication or just local memory.

The pool of memory pages that each of these nodes contributes forms the global shared memory that is available for applications running in this system.

Every address in this system will be uniquely identified by a combination of the node identifier and the page frame number.

The node where a page is located is typically referred to as the home node for that page.

Let's assume that the system needs to support the case of multiple readers and multiple writers.

In order for this system to be performant and achieve low latency, the DSM layer needs to incorporate caching. Pages will be cached on the nodes where they are accessed.

The home node for a page will be responsible for driving all of the coherence operations related to that page. As a result, all of the nodes in the system are responsible for some part of the management of the overall distributed memory.

The home node will have to keep track of the state for its memory pages:

- pages accessed

- modifications

- caching enabled/disabled

- lock status

All of this information is used for enforcing the sharing semantics that a given DSM will implement.

When a particular page is accessed repeatedly, and sometimes exclusively, by a node that is not its home node, it becomes too expensive to continually contact the home node to perform state updates.

One mechanism that is useful in DSM systems is to separate the distinction of home node from an owner node. The owner is the node that currently owns the page, and can control all of the state modifications and drive the coherence mechanisms.

The owner node may be different from the home node, and the owner node may change, as a page is accessed by different nodes through the lifetime of an application's execution.

The role of the home node then becomes to keep track of who is the current owner of a given page that maps to its physical memory.

In addition to creating page copies via caching, page replicas can be explicitly created for load balancing, performance or reliability reasons. In datacenter environments, it makes sense to triplicate shared state: on the main machine, on a nearby machine in the same building, and on a remote machine in another datacenter. The consistency of these nodes is either managed by the home node or some manager node.

Summarizing DSM Architecture

Indexing Distributed State

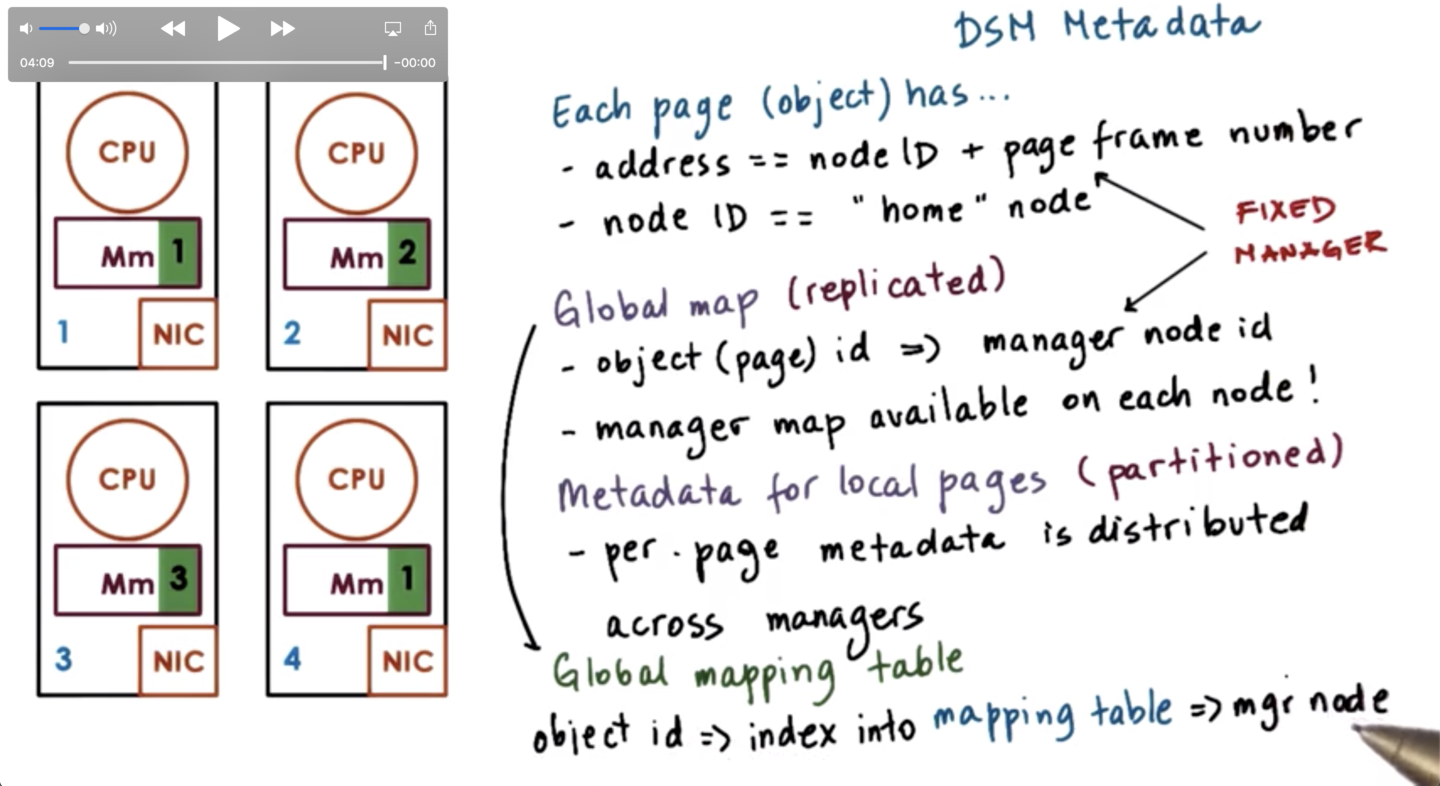

When creating distributed memory systems, it's important to understand how we can determine where a particular page is physically located within the system.

In order to do this, the DSM component has to maintain some metadata. Each page has an address, which is some combination of the node ID and the page frame number on that node.

The address directly identifies the manager/home node that knows everything about that particular page. The manager information is available on every node in the system.

This can be captured via a global map - which takes in a page id and returns a manager id - and is replicated on each node.

Each manager will maintain the per-page metadata that is necessary to perform the specific access to that page or force its consistency.

This means that the metadata for local pages is partitioned across the system, while the manager information for every page is replicated.

Certain bits from the address are used to identify the manager. There will be a fixed manager identified from that mapping function. If we want some additional flexibility we can take the object id and use it as an index into a global mapping table that will give a manager node.

In this approach, we can change the manager node by updating the mapping table. We don't need to change the object identifier.

Implementing DSM

One thing to consider when implementing a DSM is that the DSM layer must intercept every single access to the shared state.

This is needed for two reasons.

First, the DSM layer needs to detect whether an access is local or remote, so that it can create and send a message requesting access if the memory is nonlocal.

Second, the DSM layers needs to detect that a node is performing an update operation to a locally-controlled portion of the shared memory, so it can trigger the necessary coherence messages.

These overheads should be avoided when accessing local, non-shared state; thus, we would like to be able to dynamically engage and disengage DSM when necessary based on the type of accesses that are being performed.

To achieve these goals, we can leverage the hardware support at the memory management unit (MMU).

If the MMU doesn't find a valid mapping for a particular virtual address in a page table or if it detects a write attempt to protected memory, it will trap into the OS.

Whenever we need to perform an access to a remote address, there will not be a valid local mapping. The hardware will generate a trap, and the OS will pass the access information to the DSM layer to send out the appropriate remote message.

Similarly, whenever content is cached on a node, the DSM layer will ensure that that memory is write-protected, which will cause a trap if anyone tries to modify it. This will turn control over to the operating system, which will pass the relevant information over to the DSM layer in order to generate coherence messages.

When implementing a DSM system, it can also be useful to leverage additional information made available by the MMU. For example, we can track whether a page is dirty or whether a page has been accessed. This can allows us to implement different consistency policies.

For an object-based DSM system that is implemented at the level of the programming language runtime, the implementation can consider similar types of mechanisms that leverage the underlying operating system services. As an alternative, everything can be realized in software.

What is a Consistency Model?

The exact details of how a DSM system will be designed depend on the consistency model the system wants to enforce.

Consistency models exists in the context of the implementations of applications or services that manage distributed state.

The consistency model is a guarantee that the state changes will behave in a certain way as long as the upper software layers follow a certain set of rules.

For memory to behave correctly, the way that the operations access memory will somehow be representative of how the operations were issued in the first place.

In addition, for memory to behavior correctly, we will need to make some guarantees that when someone is trying to read a memory location, the value that they see will be representative of what was written to that location recently.

The consistency models states that the memory behaves correctly if and only of the software follows certain rules. This implies that the softwares needs to use certain APIs for memory access, or that the software needs to set certain expectations based on the memory guarantees or lack thereof.

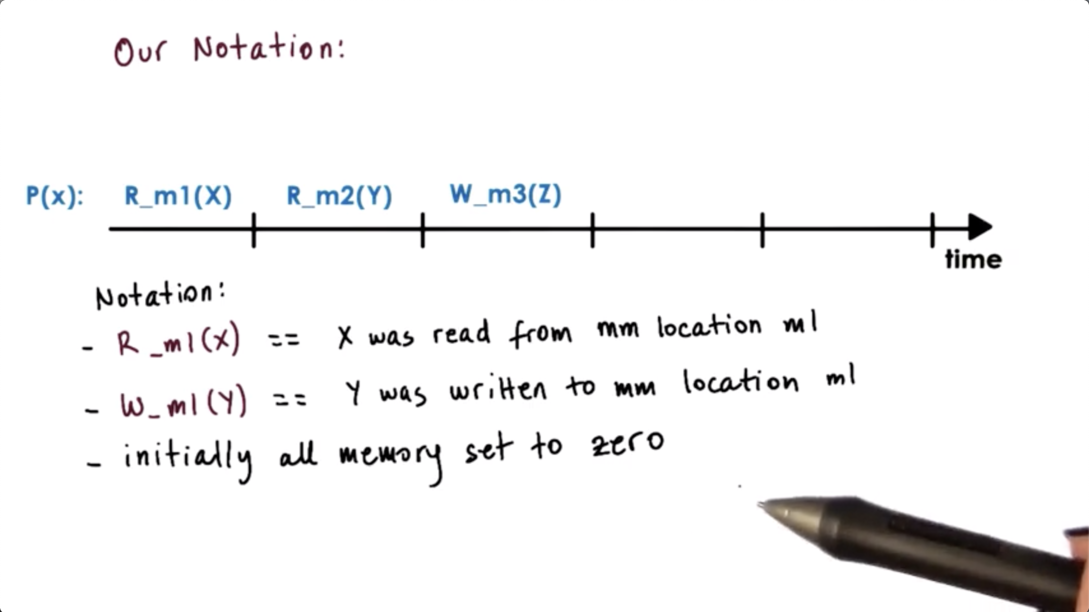

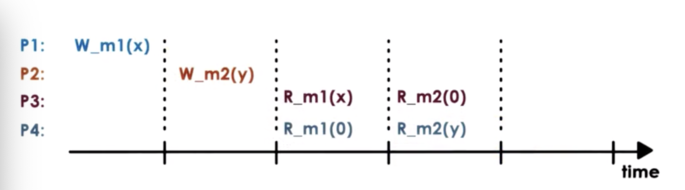

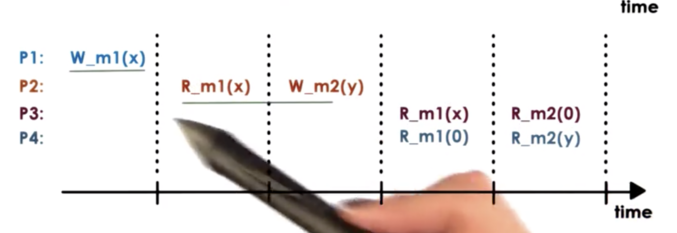

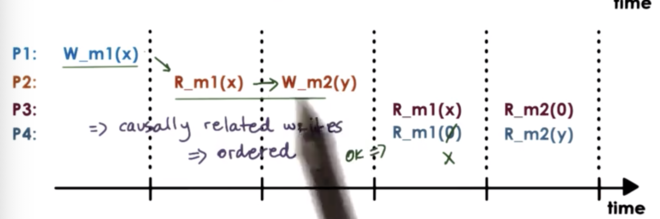

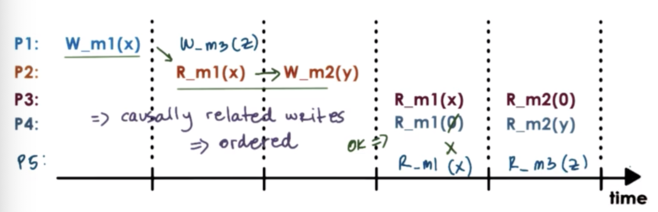

Our notation for consistency models:

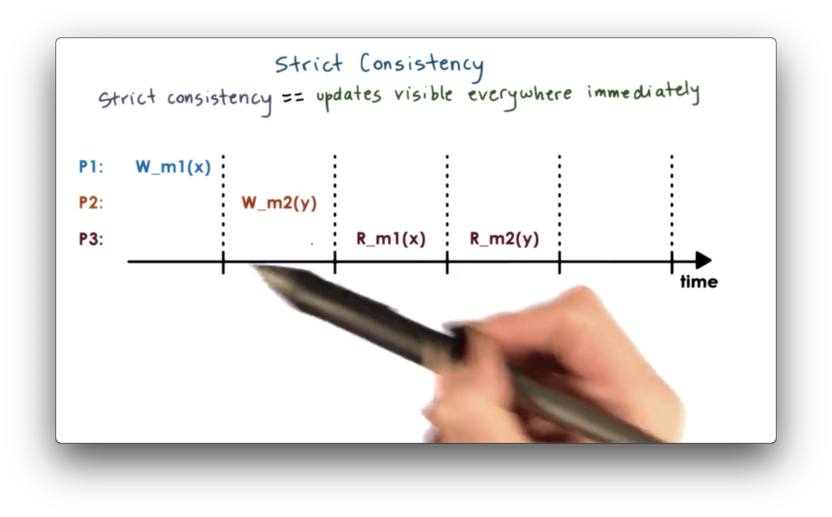

Strict Consistency

Theoretically, for a perfect consistency model, we would like to achieve absolute ordering and immediate visibility of any state update and access.

We also want this to be in the exact same manner as the updates were performed in realtime. In this model, every node in the system will see all the writes in the system in the exact same order immediately as they are applied. This is only possible if changes are instantaneous and immediately visible anywhere.

In practice, even on a single SMP system, there are no guarantees on the ordering of accesses from different cores unless we use some additional locking and synchronization primitives.

In distributed systems, additional latency and the possibility of message loss or reordering make strict consistency impossible to guarantee.

While strict consistency is a nice theoretical model, it is not sustainable in practice. Other consistency models are used instead.

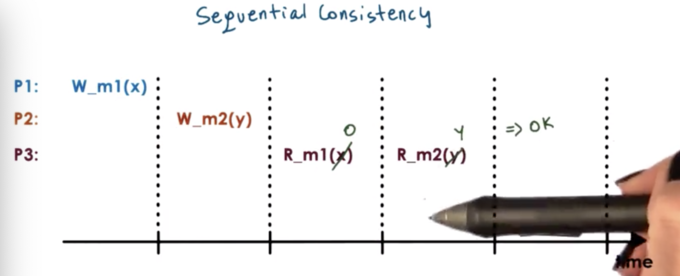

Sequential Consistency

Given that strict consistency is next to impossible to achieve, the next best option with reasonable cost is sequential consistency.

With sequential consistency, it's not important that we see updates immediately. Rather, it's important that the ordering the way see correspond to a possible ordering that can be achieved by the operations that were applied.

In the above, example, it is possible to see X and m1 and then see Y at m2. It is also possible to see 0 at m1 and then Y at m2. It is not illegal to see Y at m2 and then 0 at m1, as the write to m1 happened before the write to m2.

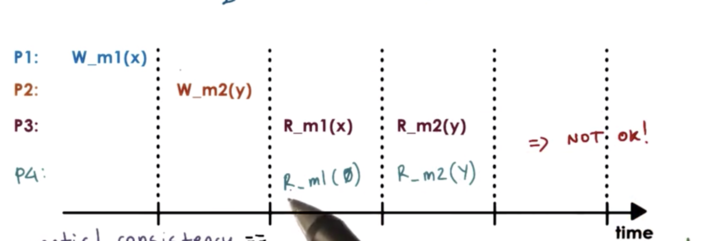

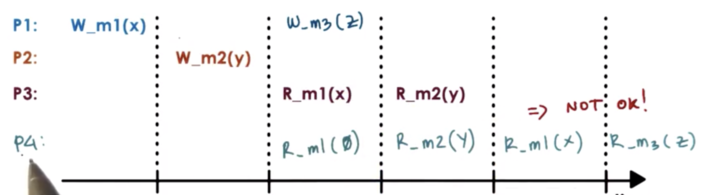

According to sequential consistency, the memory updates from different processors may be arbitrarily interleaved.

However, if we let one process see one ordering of the updates, we have to make sure that all other processes see the same ordering of those updates.

In the above case, we cannot let P3 observe one value at a m1 while concurrently showing a different value to P4, which is also accessing m1.

In sequential consistency, all processes will see the same interleaving. This interleaving may not correspond to the real way in which these operations were ordered, but it is guaranteed that every process in the system will see the same sequential ordering of the updates.

One constraint of the interleaving is that the updates made by the same process will not be arbitrarily interleaved. Operations from the same process always appear in the order they were issued.

For example, it would not be possible for P4 to read Z at m3 and then read X at m3.

Causal Consistency

Forcing all processes to see the exact same order on all updates may be an overkill.

P3 and P4 may do very different things with the values at m1 and m2, and it may not be necessary that they see the same exact value in a given moment.

Furthermore, the update to m2 was not dependent on the update to m1.

In this example, the value at m2 was written after the value at m1 was read. In this case, there may be a relationship between the update at m2 and the value at m1. The value written to m2 may depend on the value read from m1.

Based on the observation of this potential dependency, it is not okay that P4 sees that value of m2 updated to Y before seeing the value of m1 updated to X.

Causal consistency models guarantee that they will detect the possible causal relationship between updates, and if updates are causally related then the memory will guarantee that those writes will be correctly ordered.

In this situation, a causal consistency model will enforce that a process must read X from m1 before reading Y from m2.

For writes that are not casually-related - concurrent writes - there are no such guarantees.

Just like before, causal consistency ensures that writes that are performed on the same processor will be visible in the exact same order on other processors.

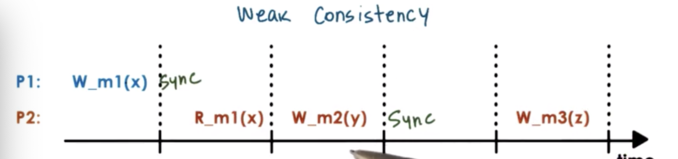

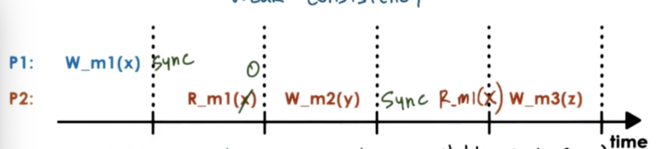

Weak Consistency

In the consistency models that we discussed so far, the memory was accessed only by read and write operations.

In the weak consistency models, it's possible to have additional operations for accessing memory.

A memory system may introduce synchronization points, as operations that are available to the upper layers of the software. In addition to telling the underlying memory system to read or write, you will now be able to tell the system to sync.

A synchronization point makes sure that all of the updates that have happened prior to the synchronization point will become visible at other processors.

Also, the synchronization point makes sure that all of the updates that have happened on other processors will become visible subsequently at the synchronizing processor in the future.

If P1 performs a synchronization operation after writing to m1, that doesn't guarantee that P2 will see that particular update at this moment. P2 hasn't explicitly synchronized with the rest of the system.

The synchronization point has to be called both by the process that is performing the updates and the process that wishes to see the updates.

Once a synchronization is performed on P2, P2 will see all of the previous updates that have happened to any memory location in the system. When P2 performs the sync, it is guaranteed to see the value of m1 at the time that P1 performed the sync.

While in this model, we use a single synchronization operation for all of the variables in the system, it is possible to have solutions where different synchronization operations are associated with different granularities.

It is also possible to separate the synchronization types into two different operations.

A system may provide an entry/acquire point, which can be invoked when a particular process requires that all of the updates performed by other processors are visible to it. This corresponds to the sync that P2 performs above.

Similarly, a system may provide an exit/release point, which can be invoked when a particular process wishes to release to all other processors the updates that it has made. This corresponds to the sync that P1 performs.

These finer-grained operations ensure that the system controls that overheads that are imposed by the DSM layer. The goal of this control is to limit the required data movement and coherence operations that will be exchanged among the nodes in the system. As a result, the DSM layer will have to maintain some additional state to keep track of the different operations it needs to support.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy