Information Security

Wireless and Mobile Security

12 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Wireless and Mobile Security

Introduction to Wifi

A typical use of WiFi is to allow WiFi-enabled personal computers or devices to access the Internet through a wireless access point (AP). Alternatively, devices can connect directly to one another wirelessly through the AP.

Devices connect to the AP wirelessly, and the AP connects to the Internet through physical wiring, often through a router provided by the Internet service provider.

In wireless networking, data is not transmitted via physical wiring, but rather through air, which is an open medium. In other words, there is no inherent physical protection in wireless communications.

Without hard wiring connecting two devices for direct communication, devices in a wireless environment must use broadcasting; that is, a sender must broadcast a message, and a receiver must be listening for a broadcast.

Wifi Quiz

Wifi Quiz Solution

Overview of Wifi Security

The earlier WiFi security standard, Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP), is easily breakable even when properly configured. The new, more secure standard is 802.11i, which WiFi Protected Access 2 (WPA2) implements. You should always use WPA2 over WEP.

Overview of 802.11i

The 802.11i standard enforces access control, and the underlying access control protocol is based on another standard, 802.1x. 802.1x is flexible because it is based on the Extensible Authentication Protocol (EAP).

EAP is designed as a carrier protocol whose purpose is to transport the messages of "real" authentication protocols, such as TLS. In other words, you can implement a host of different authentication methods on top of EAP, and therefore on top of 802.1x.

The more advanced EAP methods, such as TLS, provide mutual authentication, which limits man-in-the-middle attacks by authenticating both the server and client. Furthermore, this EAP method results in key material, which can be used to generate dynamic encryption keys.

Additionally, 802.11i follows strong security practices. For example, it uses different keys for encryption and integrity protection, and also uses more secure encryption schemes - AES in particular.

Wifi Security Standards Quiz

Wifi Security Standards Quiz Solution

Overview of Smartphone Security

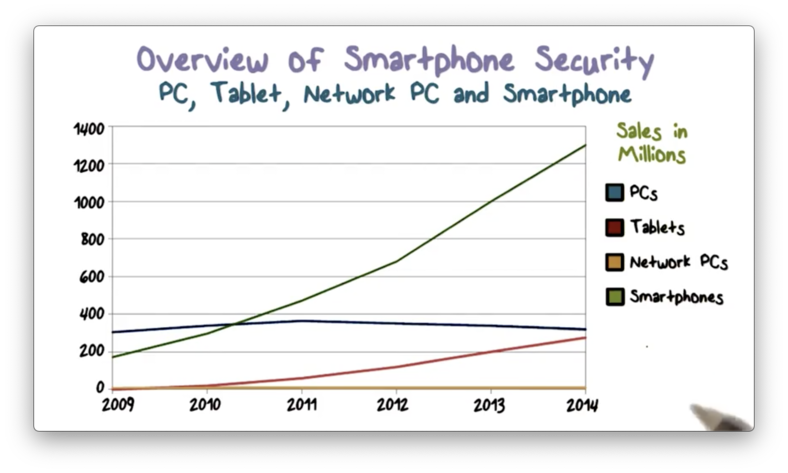

The following plot shows a significant increase in smartphone sales in recent years.

People use smartphones now more than ever, and we are using them for more and more essential tasks. Therefore, we must examine the security of smartphones.

Overview of iOS Security

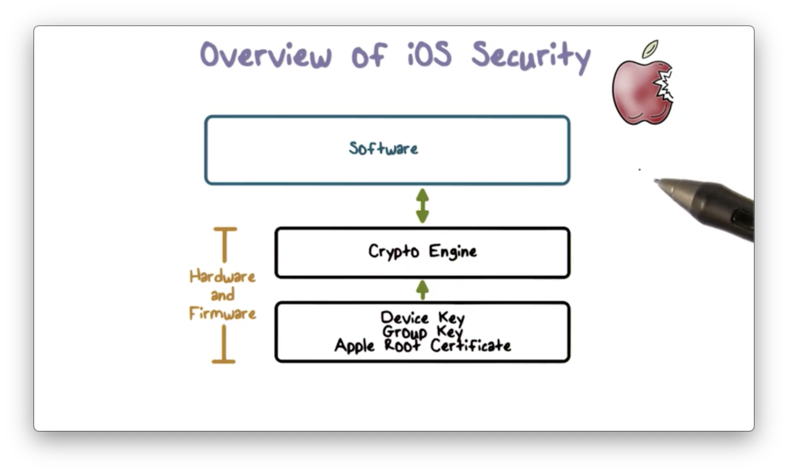

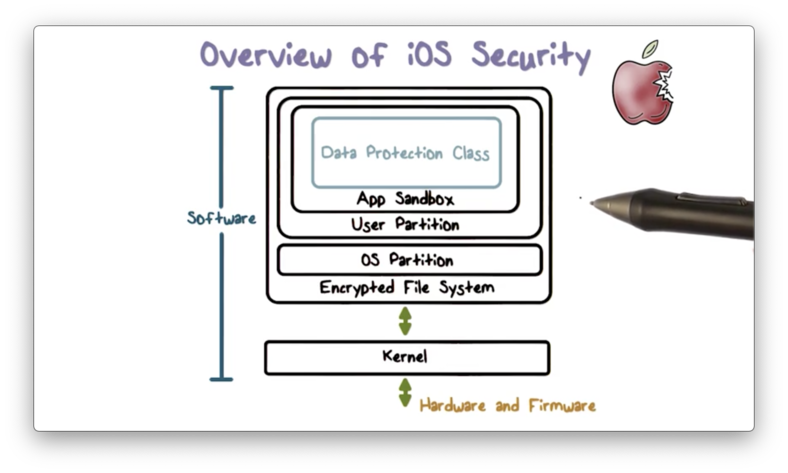

The iOS security architecture combines both hardware and software features to provide security to iOS devices such as iPhones and iPads.

The architecture contains built-in cryptographic capabilities - for example, the cryptographic engine and keys are embedded into the hardware - for supporting data protection via confidentiality and integrity.

The architecture also provides powerful isolation mechanisms. For example, it uses app sandboxing to protect app security. These sandboxes enable apps to run in isolation, free from interference from other apps. Additionally, sandboxing helps to ensure the integrity of the overall system. In other words, even if an app is compromised, its capability to damage the system is minimal.

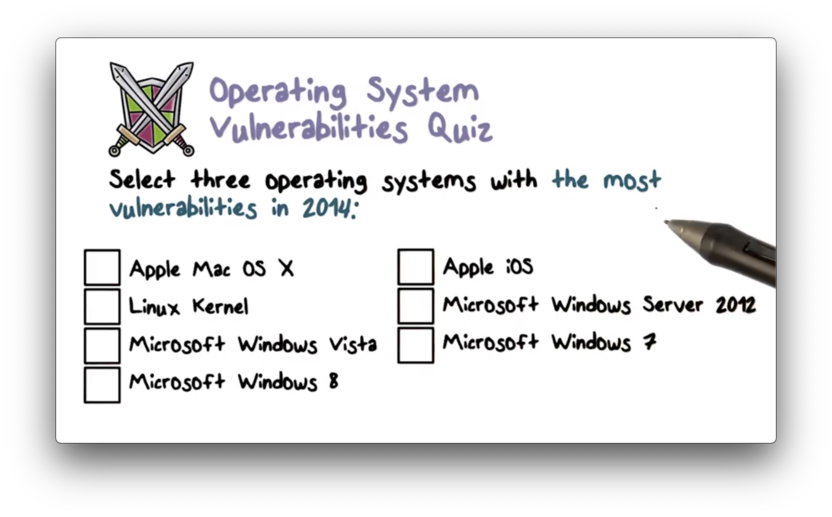

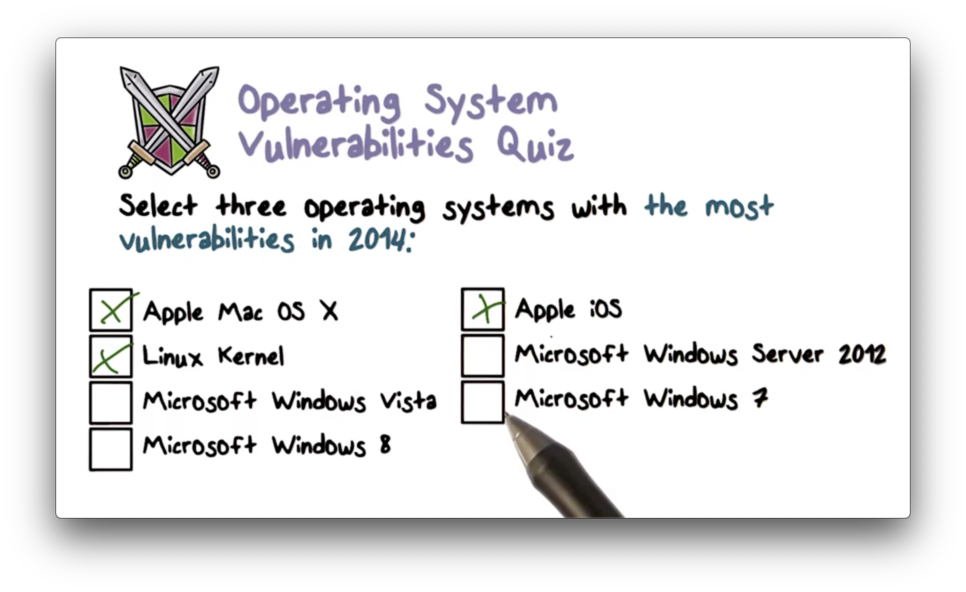

Operating System Vulnerabilities Quiz

Operating System Vulnerabilities Quiz Solution

Betcha thought it was gonna be all Microsoft, didn't you? Read more here.

Hardware Security Feature

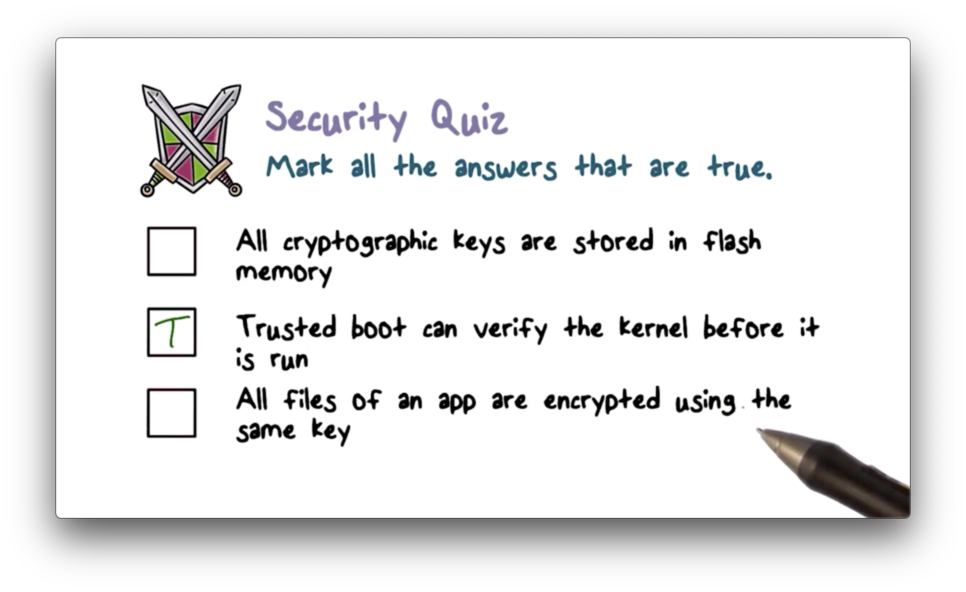

Each iOS device has a dedicated AES-256 cryptographic engine built into the direct memory access path between the flash storage and the main system memory, which makes file encryption/decryption highly efficient.

The device's unique ID (UID) and group ID (GID) are AES 256-bit keys fused into the secure enclave hardware component during manufacturing. Only the cryptographic engine, itself a hardware component, can read these keys directly. All other firmware and software components can only see the result of an encryption or decryption operation.

A UID is unique to a device and is not recorded by Apple or its suppliers. GIDs are common to all processors in a class of devices, such as those using the Apple A8 processor, and are used for tasks such as delivering system installations and updates.

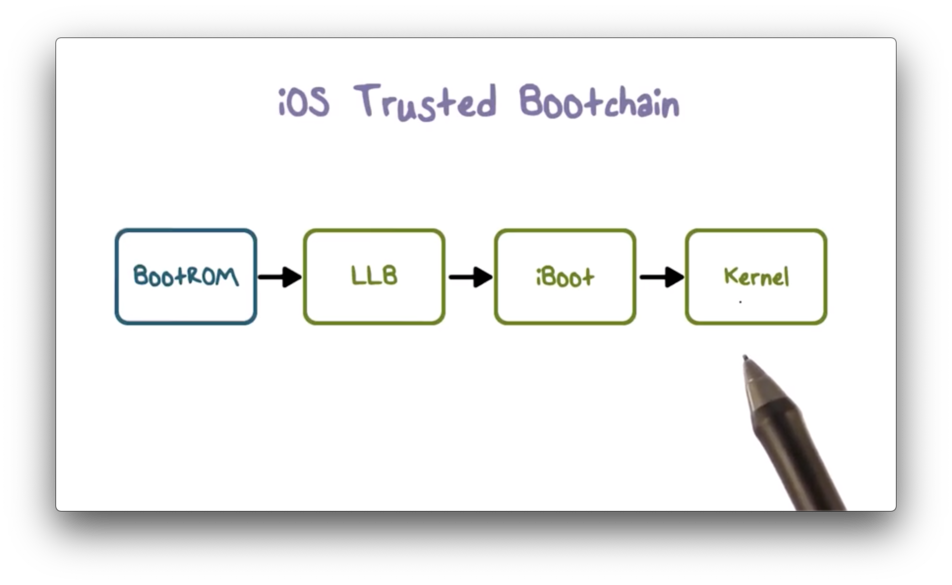

iOS Trusted Bootchain

iOS uses a trusted bootchain to establish the security of an iOS device on boot. Each step in the bootchain (except the first) only executes once the previous step has verified it.

When an iOS device is turned on, each application processor immediately executes code from a section of read-only memory known as the BootROM. This immutable, implicitly-trusted code, known as the hardware root of trust, is burned into the hardware during chip fabrication.

The BootROM code contains the Apple root CA public key, which is used to verify that Apple has signed the low-level boot loader (LLB) before allowing it to load. When the LLB finishes its tasks, it verifies and runs the next stage boot loader, iBoot, which in turn verifies and runs the iOS kernel.

This secure bootchain helps ensure that the lowest levels of software are not tampered with, and enforces that iOS only runs on validated Apple devices.

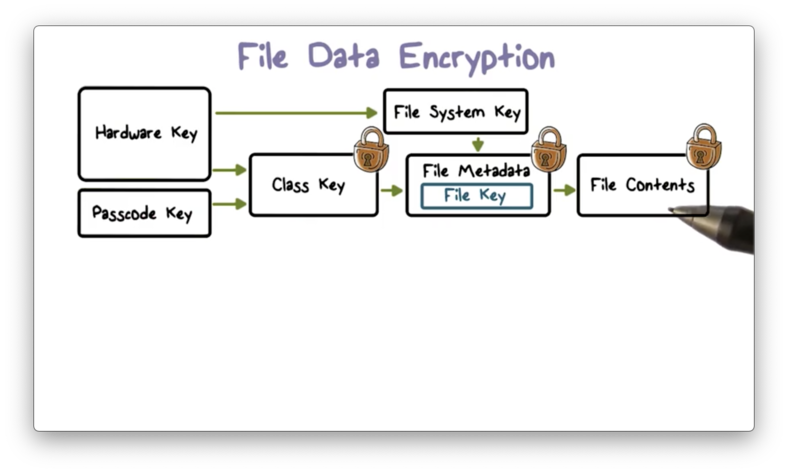

File Data Encryption

In addition to the cryptographic capabilities built into the hardware of each iOS device, Apple uses a technology called data protection to further secure data stored in flash memory.

Data protection enables a high level of encryption for user data. Critical system apps such as Messages, Mail, and Calendar use data protection by default, and third-party apps installed on iOS 7 or later receive this protection automatically.

Data protection constructs and manages a hierarchy of keys - such as class, file, and filesystem keys - that builds on the hardware encryption technologies built into each iOS device.

Each time a file is created, the data protection system generates a new 256-bit file key, which it gives to the hardware AES engine. The engine encrypts the file using this key - via the CBC mode of AES - every time the file is written to flash memory.

Every file is a member of one or more file classes, and each class is associated with a class key. A class key is protected by the hardware UID and, for some classes, the user's passcode as well. The file key is encrypted with one or more class keys, depending on which classes the file belongs to, and the result is stored in the file's metadata.

The metadata of all files in the filesystem is encrypted using the same random key: the filesystem key. The system generates this key when iOS is first installed, or when a user wipes and restarts the device.

When a file is opened, it's metadata is decrypted first using the filesystem key, which reveals the encrypted file key. Next, the file key is decrypted using one or more class keys. Finally, the file key is used to decrypt the file as it is read from flash memory.

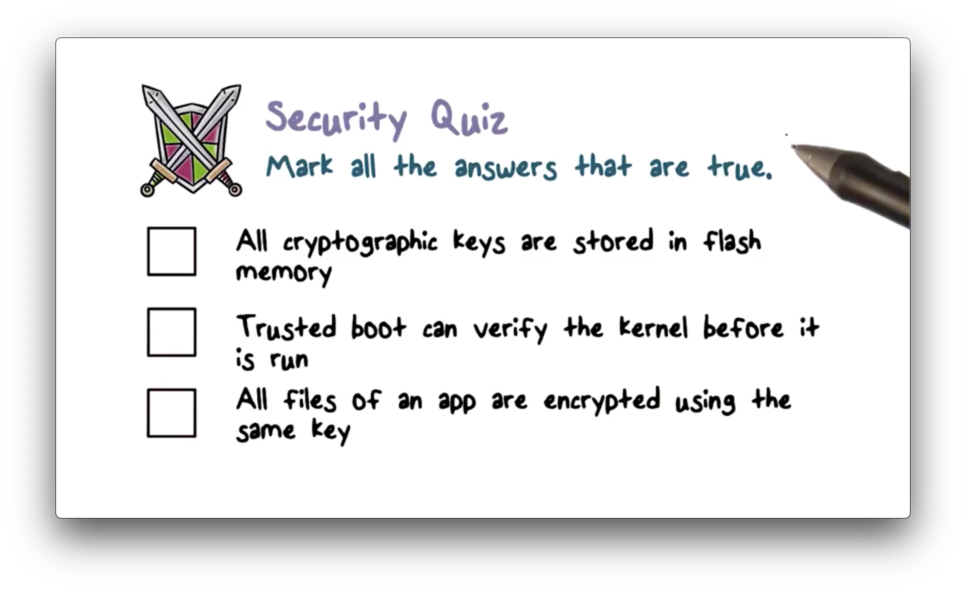

Security Quiz

Security Quiz Solution

Mandatory Code Signing

The iOS kernel controls which user processes and apps are allowed to run. iOS requires all executable code to be signed with an Apple-issued certificate to ensure that all apps come from a known and approved source and have not been modified in unauthorized ways.

Apps provided with the device, such as Mail or Safari, are already signed by Apple. Third-party apps must also be certified and signed using an Apple-issued certificate.

By requiring all apps on the device to be signed, iOS extends the concept of chain of trust from the kernel to the apps and prevents third-party apps from uploading unauthorized code or running self-modifying code.

A user-space daemon examines executable memory pages as they are loaded by an app to ensure that the app has not been modified since it was installed or explicitly updated.

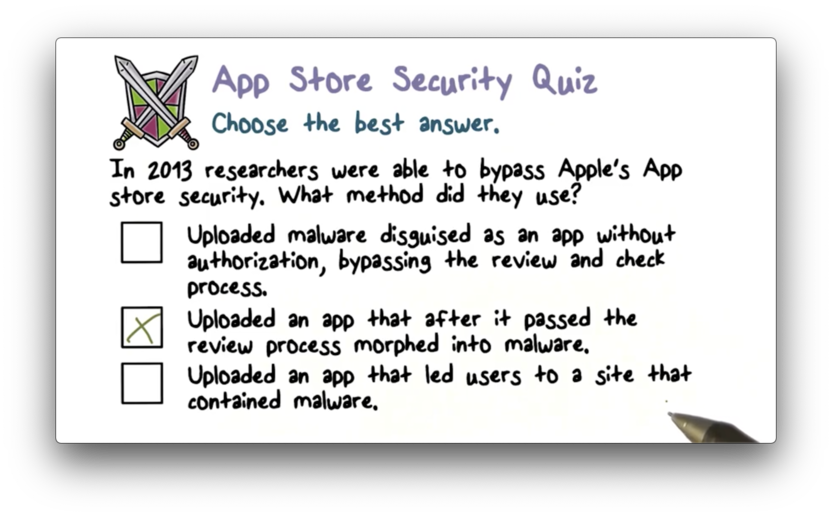

Restricted App Distribution Model

A developer must first register with Apple and join the iOS developer program if they want to develop apps for iOS devices. Apple verifies the real-world identity of each developer - whether an individual or business - before issuing a certificate.

Developers use their certificates to sign their apps before submitting them to the App Store for distribution, which means that every app in the App Store can be traced back to an identifiable entity. Associating apps with the real-world identities of their developers serves as a deterrent to submitting malicious code.

Furthermore, Apple reviews all apps in the App Store to ensure that they operate as described and requires iOS devices to download apps exclusively from the official Apple App Store.

The restricted app distribution model, combined with app signing, makes it very difficult to upload malware to the App Store.

App Store Security Quiz

App Store Security Quiz Solution

Read more here.

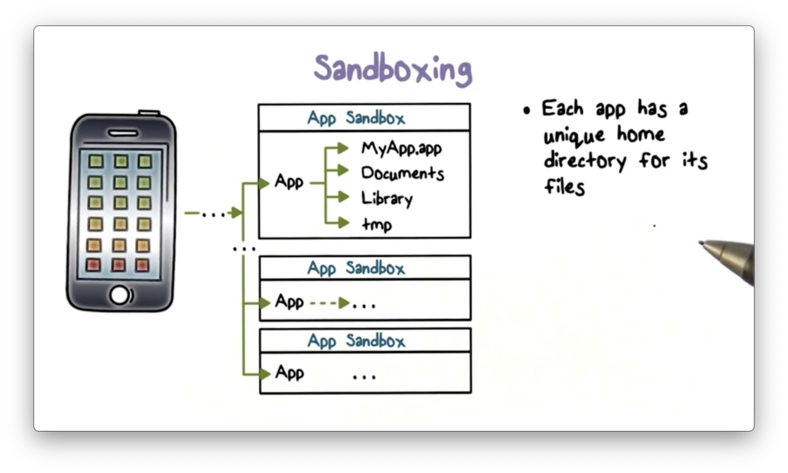

Sandboxing

Once an app resides on a device, iOS enforces additional security measures to prevent it from compromising other apps or the rest of the system.

Each app receives a unique home directory for its files, which is randomly assigned when the app is installed. This directory serves as a sandbox; that is, iOS restricts apps from accessing information outside of the directory.

If a third-party app needs to access external information, it must use services explicitly provided by iOS. This requirement prevents apps from unauthorized access or modification to information it does not own.

Additionally, the majority of iOS processes, including third-party apps, run as a non-privileged user, mobile, which does not have access to crucial system files and resources. The iOS APIs do not allow apps to escalate their own privileges to modify other apps or iOS itself.

Finally, the entire iOS partition is mounted as read-only, and unnecessary tools such as remote login services are not included in the system software.

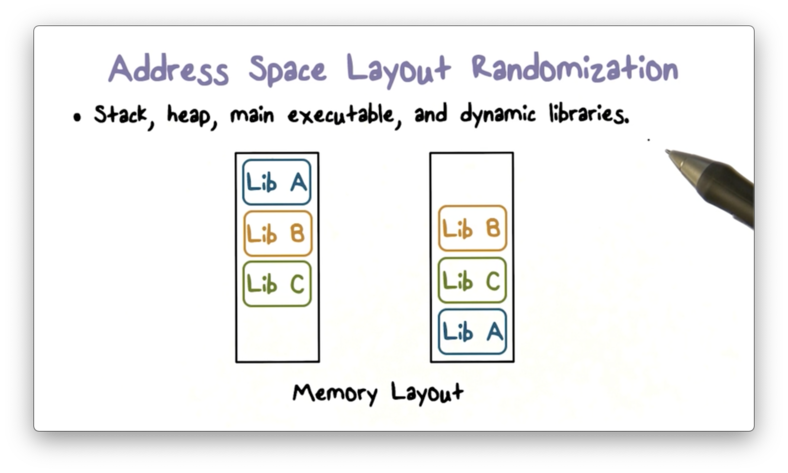

Address Space Layout Randomization

iOS has several other runtime security measures. One such measure is address space layout randomization (ASLR), which protects against the exploitation of memory corruption bugs.

A common class of attack - which includes the return-to-libc attack - involves an attacker estimating the addresses of nearby system functions and calling these functions to perform malicious actions or escalate privileges.

As a countermeasure, iOS randomly arranges the different program components in memory upon app initialization. This randomization makes it virtually impossible for an attacker to locate a useful library function to exploit.

iOS Security Quiz

iOS Security Quiz Solution

Read more here.

Data Execution Prevention

Another runtime security feature that iOS provides is data execution prevention. Data execution prevention is an implementation of the policy the makes writeable and executable pages mutually exclusive.

Specifically, iOS marks pages that are writable in runtime, such as pages that contain the stack, as non-executable, using the ARM processor's execute never feature. Reciprocally, iOS marks executable memory pages, such as pages that hold code instructions, as non-writeable.

This mutual exclusivity helps prevent code-injection attacks. To inject code, an attacker must write instructions into a memory page and then subsequently execute those instructions. Since a page cannot be both writeable and executable, an attacker can never execute injected code.

Passcodes and Touch ID

By setting up a device passcode, a user both prevents unauthorized access to their device and automatically enables data protection, which encrypts all of their files.

iOS supports 4-digit numeric and arbitrary-length alphanumeric passcodes. To discourage brute-force attacks, the iOS interface enforces escalating time delays after the entry of an invalid passcode. Users can choose to have the device automatically wiped if the passcode is entered incorrectly after ten consecutive attempts.

A user can opt to use Touch ID instead of a passcode. Touch ID is the fingerprint-sensing system that makes secure access to the device faster and easier.

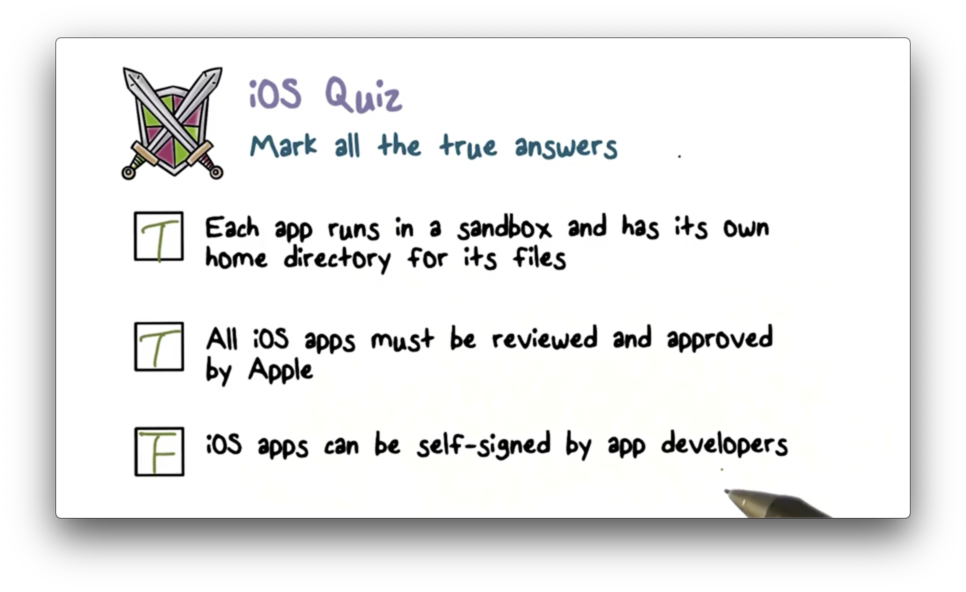

iOS Quiz

iOS Quiz Solution

Android Security Overview

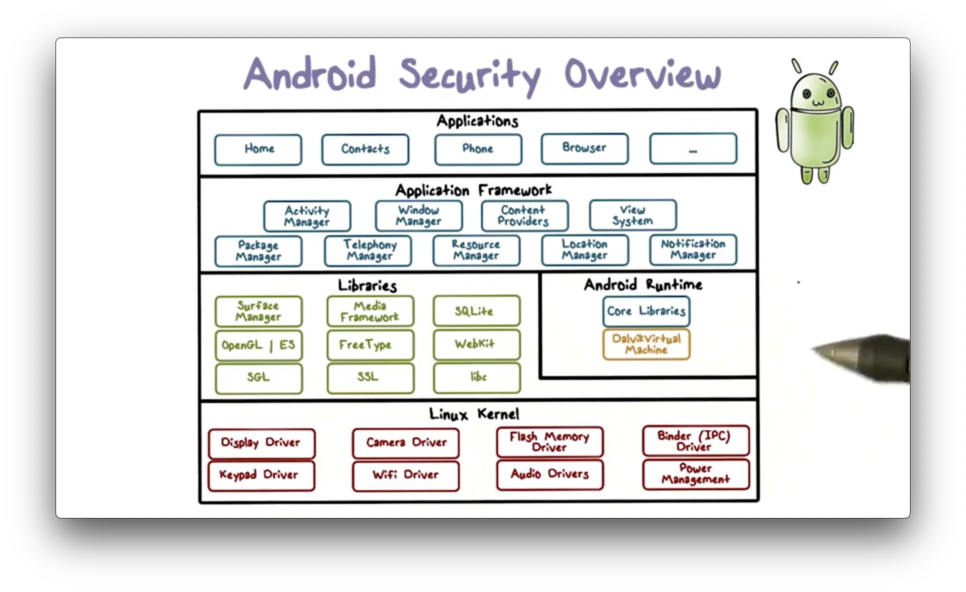

Android is implemented as a software-stack architecture, consisting of a Linux kernel, a runtime environment with corresponding libraries, an application framework, and a set of applications.

The Linux kernel sits at the lowest level of the architecture stack and provides a level of abstraction between device hardware and the upper layers of the stack.

Apps are commonly written in Java, which is first compiled to Java Virtual Machine (JVM) bytecode and then translated to bytecode that runs on the Dalvik virtual machine DVM, a virtual machine optimized for mobile devices. In particular, the DVM optimizes for memory, battery life, and performance.

The Android core libraries are Java-based libraries that are used for application development. Most of these libraries do not perform any work but instead serve as thin Java wrappers around a set of C and C++ based libraries. These underlying libraries fulfill a wide range of functions, including graphics rendering in 2D and 3D, SSL, and more.

The application framework is a set of services that collectively form the environment in which Android apps run. This framework allows apps to be constructed using reusable, interchangeable, and replaceable components.

Furthermore, an individual app can publish components and data for use by other apps. This capability allows apps to build on top of other apps, in addition to using default components exposed by the framework.

At the top of the software stack are the apps, which include apps that come with the device - such as contacts, phone, and email - as well as any other third-party apps the user has downloaded.

Application Sandbox

Apps that run in virtual machines are essentially sandboxed in runtime. Sandboxed apps cannot directly interfere with the operating system or other apps, nor can they directly access the device hardware. Each app is granted a set of permissions at install time and can only perform operations permitted by these permissions.

Android assigns as unique user ID (UID) to each app and runs it with that UID in a separate process. The kernel enforces security between apps and the system at the process level through standard Linux facilities, using the user and group IDs associated with an app to determine which system resources and functions an app can access.

By default, apps have limited access to the operating system and other apps. The operating system denies unauthorized requests - such as one app trying to read data owned by another app, or an app attempting to dial the phone without permission - unless the appropriate user privileges are present.

An app can announce the permissions it needs, and a user can grant these permissions during app installation. The permissions are typically implemented by mapping them to Linux groups that have the necessary read/write access to relevant system resources, such as files and sockets.

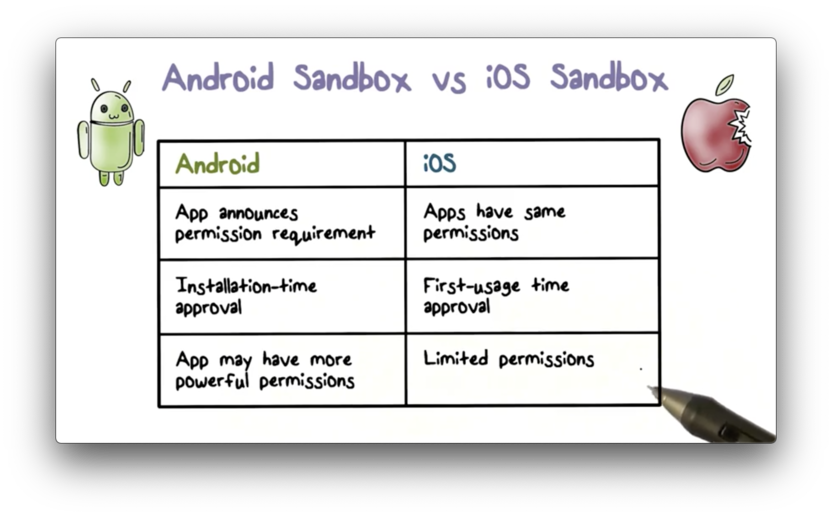

Android Sandbox vs iOS Sandbox

From a security perspective, one of the main differences between the Android and iOS sandbox is how they handle permissions.

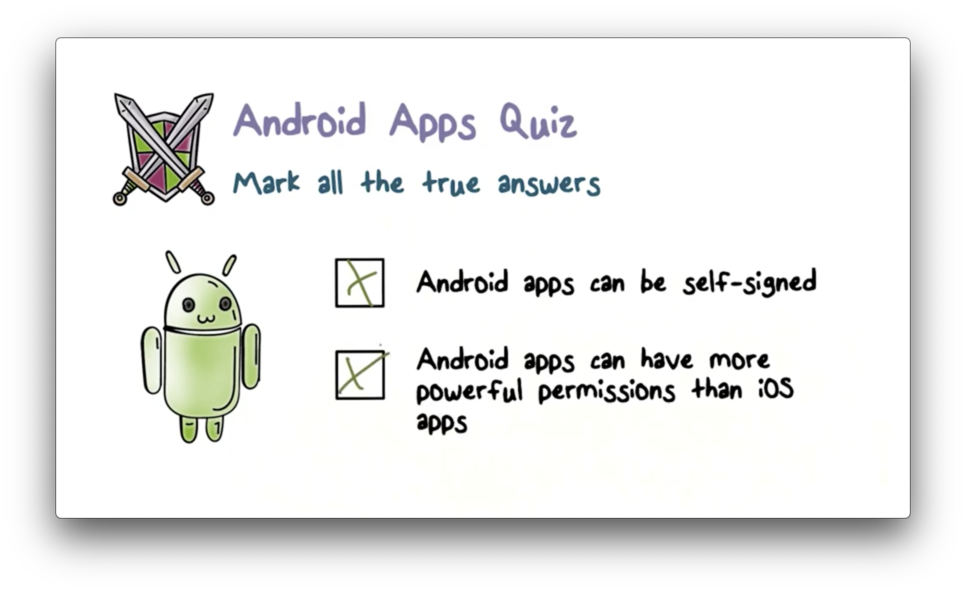

Android apps can announce the permissions that they require, and users can approve these permissions at install time. Notably, Android apps can ask for very powerful permissions.

All iOS apps have the same set of basic permissions. If an app needs to access system resources or data - such as the user's address book - user approval is required at the first access request. In general, iOS apps have limited permissions.

Code Signing

Android also takes a very different approach than iOS in terms of code signing. In particular, all Android apps are self-signed by developers. A developer can create a public key, self-sign it to create a certificate, and then use the key to sign apps.

There is no central authority that signs third-party Android apps, and there is no vetting process for third-party app developers. Anybody can become an Android app developer, self-sign their apps, and upload them to the Google Play Store.

While Apple uses code signing to identify developers and verify app executables, Android uses code signing for different purposes.

Specifically, Android devices use code signing to ensure that updates for an app are coming from the same developer that created the app. Additionally, code signing helps manage the trust relationship between apps so that they can share code and data.

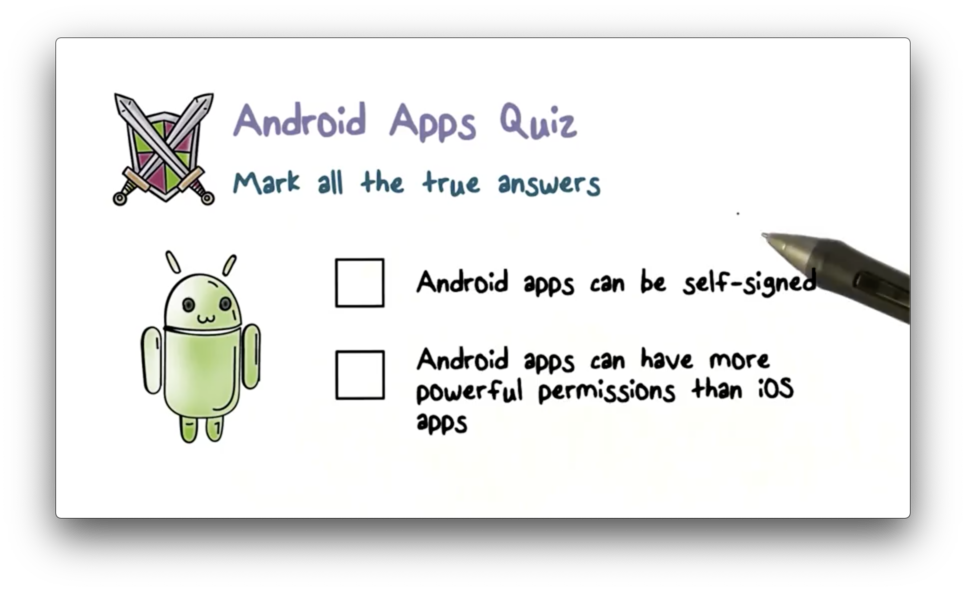

Android Apps Quiz

Android Apps Quiz Solution

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy