Information Security

Symmetric Encryption

11 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Symmetric Encryption

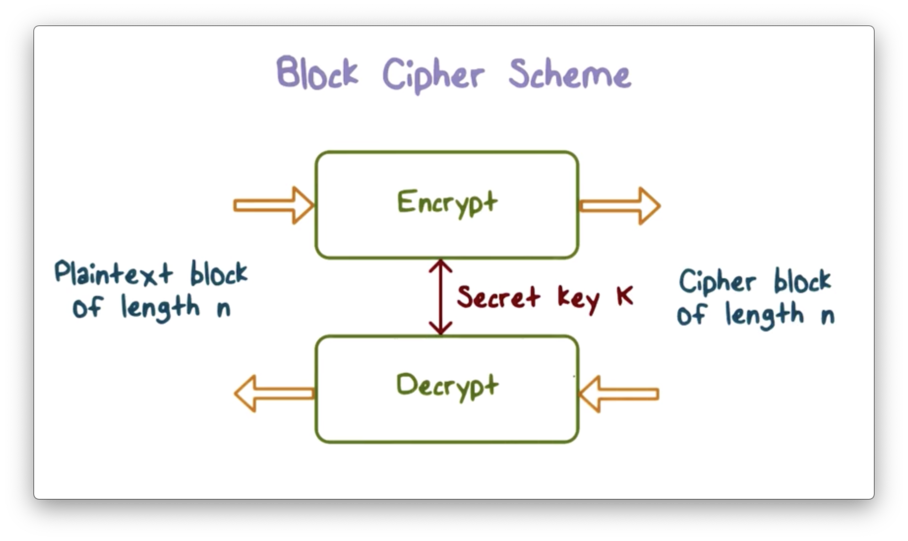

Block Cipher Scheme

Most symmetric encryption schemes are block ciphers. A block cipher encrypts a plaintext block of length n into a ciphertext block of length n using a secret key k and decrypts the ciphertext using the same k.

Block Cipher Primitives

The goal of encryption is to transform plaintext into an unintelligible form. Since we assume that an attacker can obtain the ciphertext, we don't want the ciphertext to convey any information about the key or the plaintext.

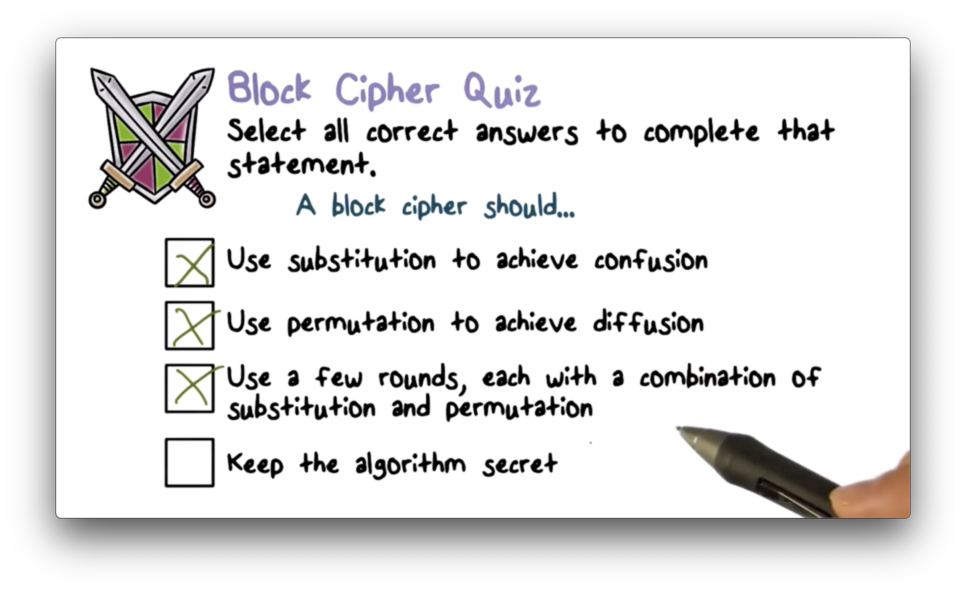

Confusion obscures the relationship between the key and the ciphertext and is typically achieved with substitution. Through confusion, the attacker cannot determine the key, even if they obtain the ciphertext.

Confusion alone is not sufficient. Even when a letter can be mapped to any other letter, an attacker can perform a statistical analysis of letter frequencies to break the scheme. For example, the most common letter in English is 'E'. If the most common letter in the ciphertext is 'Q', we can be confident that 'E' maps to 'Q'.

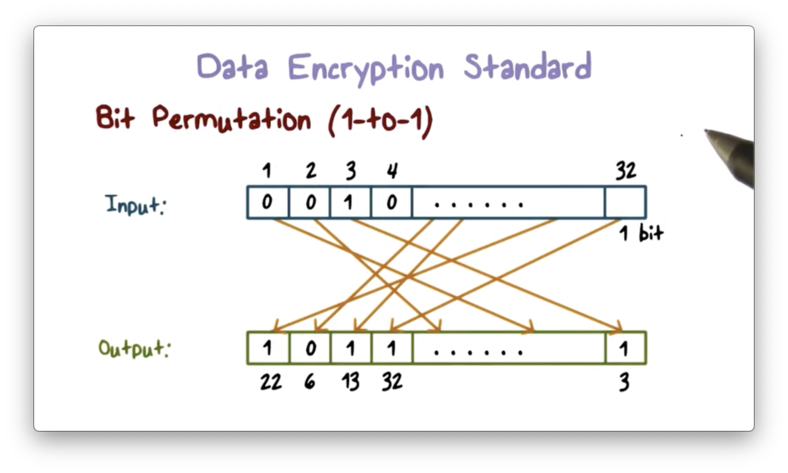

The second principle that we need is diffusion. Diffusion spreads the influence of one plaintext bit over many ciphertext bits to hide the statistical properties of the plaintext. We can achieve diffusion with permutation.

For example, instead of mapping an English letter to another English letter, we can map a letter to parts of many 8-bit letters. This approach renders the frequency distribution of English letters less useless.

We need this combination - confusion and diffusion - to affect every bit in the ciphertext, so a block cipher typically runs for multiple rounds. The initial round affects some parts of the ciphertext, and subsequent rounds further propagate these effects into other parts of the ciphertext. Eventually, all bits of ciphertext are affected.

Block Cipher Quiz

Block Cipher Quiz Solution

Data Encryption Standard

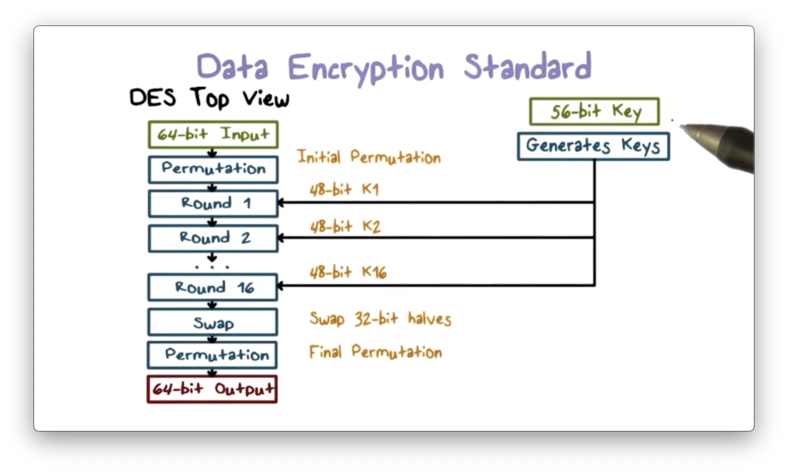

A widely used symmetric encryption scheme is based on the Data Encryption Standard (DES), which was established in 1977 and standardized in 1979.

In DES, the key is 64 bits (8 bytes) long. For each byte, there is one parity bit, so the actual value of the key is only 56 bits. DES receives a 64-bit plaintext block as input and produces a 64-bit ciphertext block.

DES contains an initial and final permutation step that remaps the positions of the bits to achieve diffusion.

In between the permutation steps, DES performs 16 rounds of operations using 16 48-bit subkeys generated from the original 56-bit key. Each round receives as input the ciphertext produced by the previous round and outputs the ciphertext used as input by the next round.

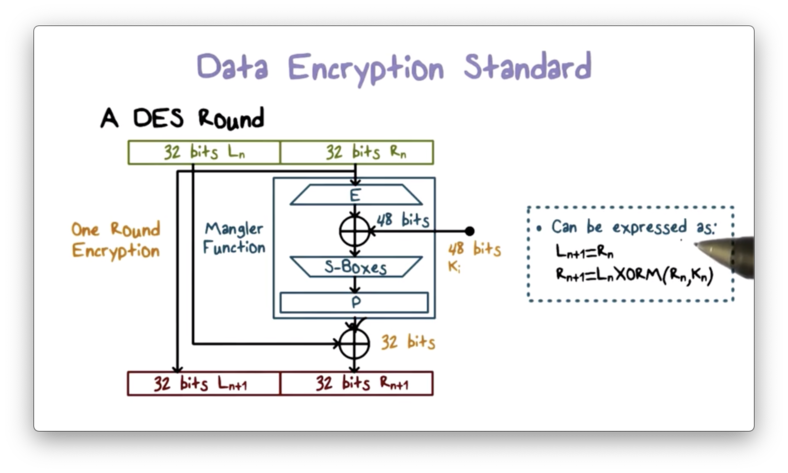

A round proceeds as follows. First, the 64-bit input is divided into two 32-bit halves. The output left half is simply the input right half. The output right half is the XOR of the input left half, and the output of a mangler function applied to the input right half.

The mangler function receives a 32-bit input, expands it to 48 bits, XORs it with the 48-bit per-round key, and then passes it to an S-box to substitute the 48-bit value back into a 32-bit value.

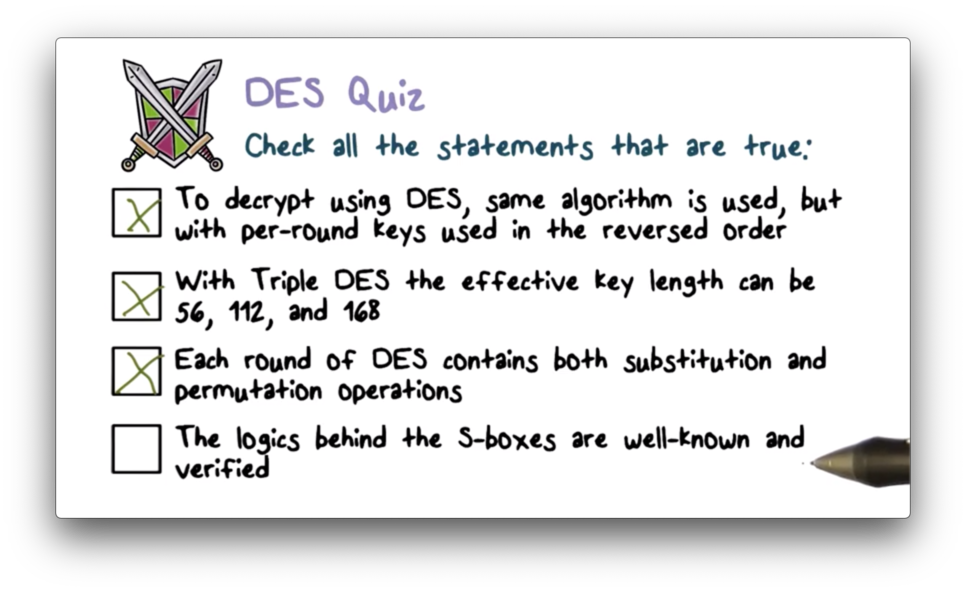

The decryption process performs the same operations as the encryption process but uses the keys in reverse order. That is, the first decryption step uses the sixteenth key, and the final step uses the first key.

Decryption

DES is a Fiestel cipher, which means that encryption and decryption differ only in key schedule. In decryption, we apply the same operations as we do in encryption, but with a reverse key sequence. Formally, round l of decryption uses subkey 16 - l + 1.

Since each encryption round swaps the right and left halves of the input, the input to each decryption round is the swap of the input. However, since each decryption round performs the same operations as encryption, the decryption input is swapped to recover the original encryption input.

After 16 rounds of decryption, the algorithm has recovered the right and left halves of the original plaintext, and the final swap arranges the halves in the correct order.

XOR Quiz

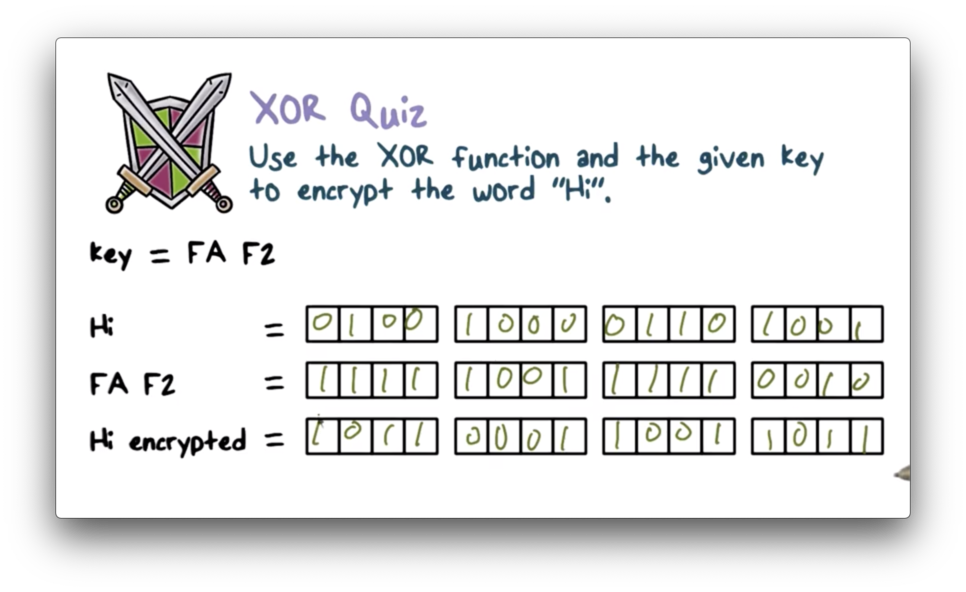

XOR Quiz Solution

"H" has an ASCII code of 72, which maps to 0b01001000, and "i" has an ASCII code of 105, which maps to 0b01101001. "F" maps to 15 (0b1111) and "A" maps to 11 (0b1001), so "FA" maps to 0b11111001 and "F2" maps to 0b11111001.

We XOR two numbers bit-by-bit, and we return 0 when the bits match and 1 otherwise. Therefore 0b0100100001101001 XOR 0b1111100111110010 is 0b1011000110011011.

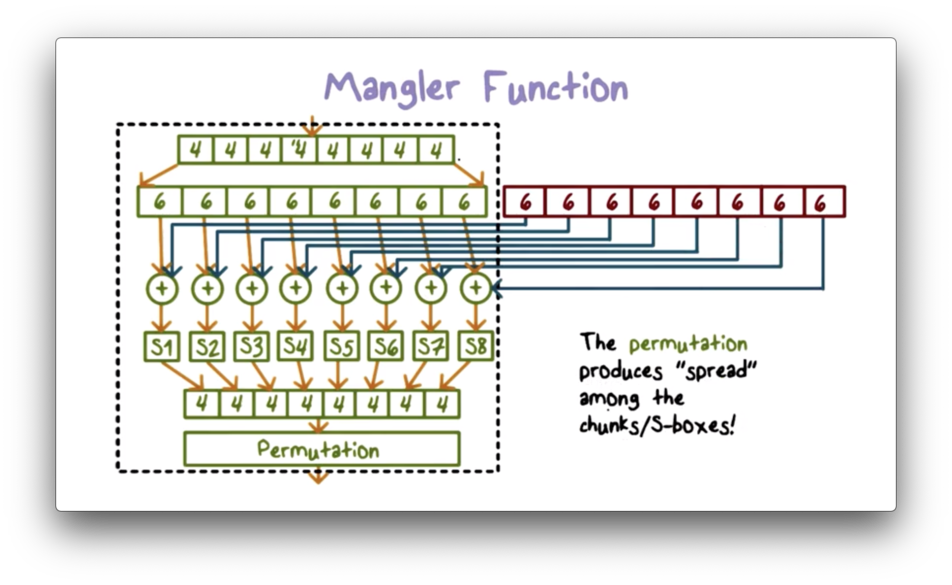

Mangler Function

The mangler function performs the bulk of the processing in a DES round. It expands the right half of the input from 32 bits to 48 bits and XORs it with the per-round key. The result is substituted back into a 32-bit value, which the function then permutates.

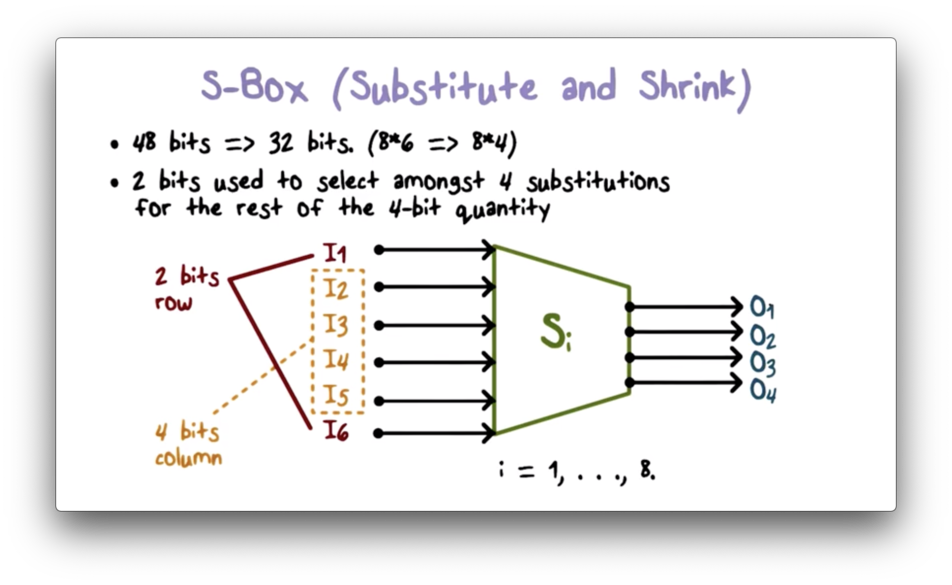

S Box

An S-box substitutes a 6-bit value with a 4-bit value using a predefined lookup table. DES uses 8 such S-boxes to substitute a 48-bit (68) value with a 32-bit (48) value. We can perform the substitution of a 6-bit value by using the outer two bits to look up the row of the S-box and the inner four bits to look up the column.

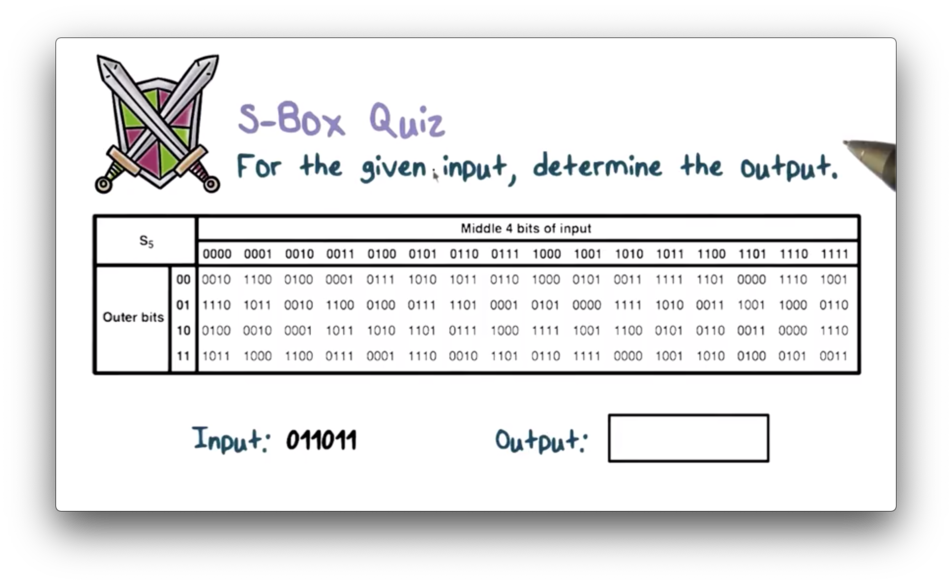

S Box Quiz

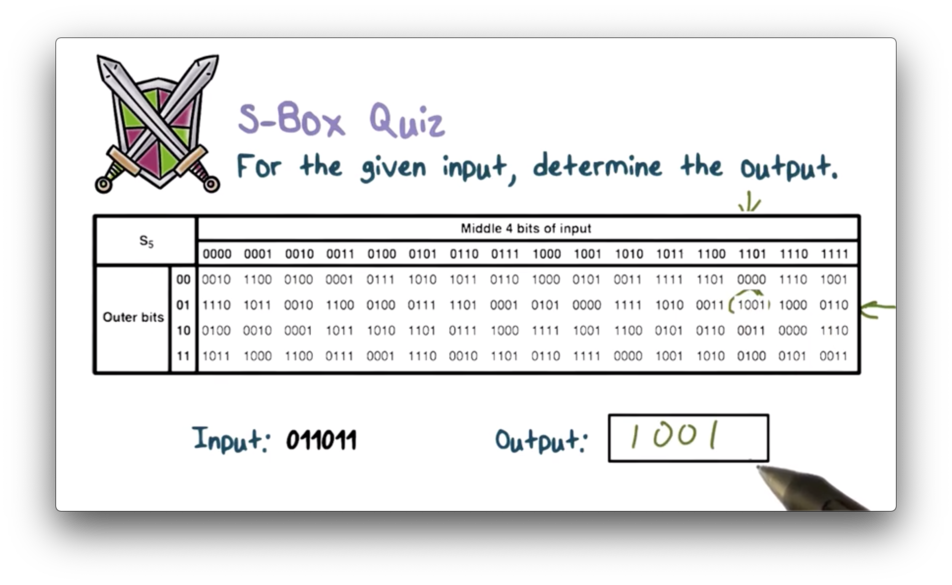

S Box Quiz Solution

Security of DES

The key size in DES is 56 bits, so there are only 2^56 possible keys. This keyspace is too small, and an attacker can use brute-force to find the correct key relatively easily using today's computers.

Another issue with DES is that the design criteria for the S-boxes have been kept secret. On the one hand, the S-boxes are resistant to attacks that were published years after DES was published, which indicates the security of the design. On the other hand, because the design criteria have been kept secret, one might wonder if the designer of DES knew about these attacks years before they were published.

One could argue that the designer should have published the design criteria so that researchers could review them and improve upon them.

Triple DES

To overcome the small keyspace that renders DES insecure, we can run DES multiple times, using a different key each time. The standard is to run it three times, and the resulting scheme is called triple DES.

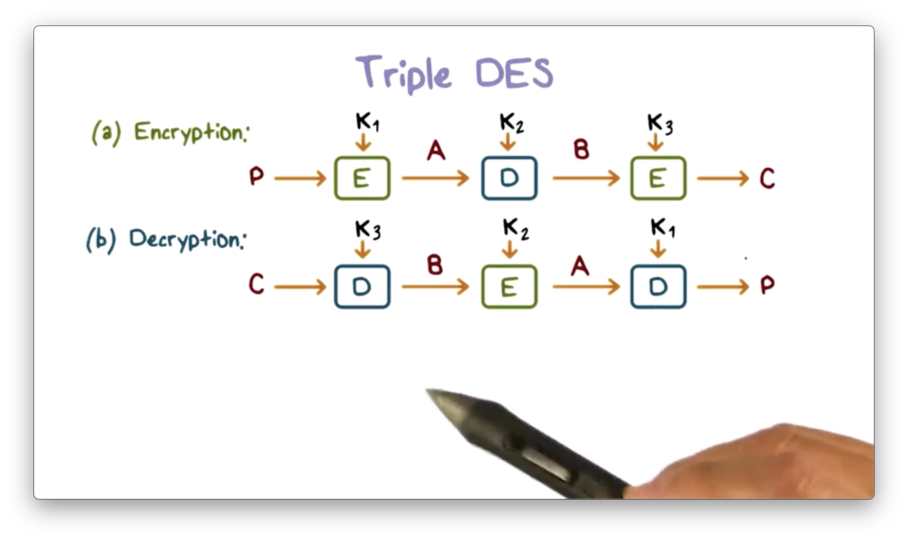

To encrypt plaintext using triple DES, we first run the encryption process with key k1, followed by the decryption process with a second key k2, followed by the encryption process with a third key k3. To decrypt a ciphertext, we run the process in reverse, decrypting with k3, encrypting with k2, and decrypting again with k1.

This order of operations is advantageous because it supports multiple key lengths. For example, if k1 and k3 are equal, the result is 112-bit DES. If all three keys are different, the effective key length is 168 bits.

Additionally, if we set k2 equal to k1, then triple DES has essentially become single DES using k3. Using this configuration, we can allow DES and triple DES to communicate with one another.

DES Quiz

DES Quiz Solution

Advanced Encryption Standard

Key length is a significant shortcoming of DES. At 56 bits long, the keyspace for DES is too small, and an attacker can use brute force to find a key with the power of modern computers. While we can use triple DES to increase the key length, running DES three times is not an efficient approach.

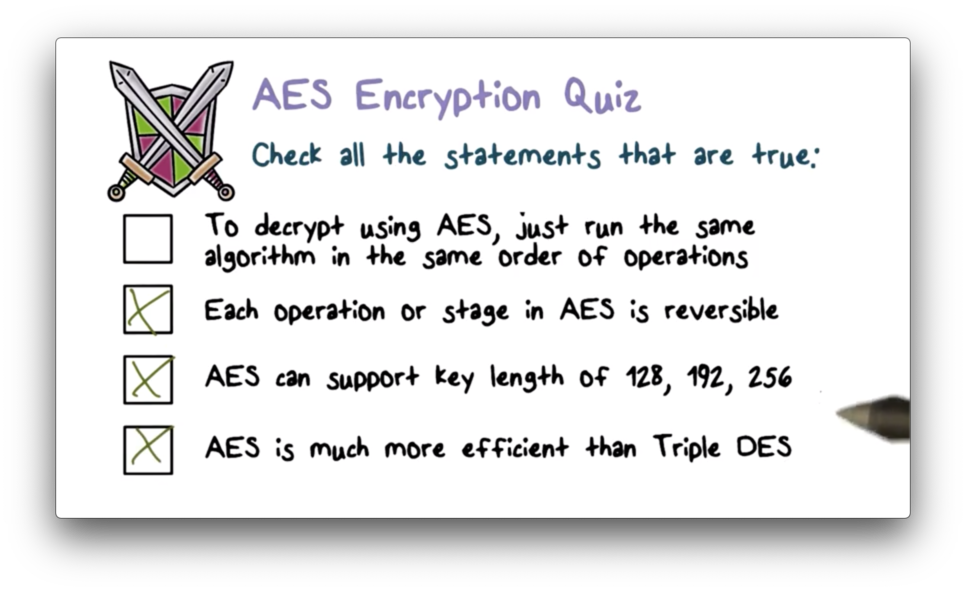

The replacement for DES is the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Like DES, AES is a block cipher. Whereas in DES, the input plaintext block is 64-bit, it is 128-bit in AES. In DES, the key length is only 56-bit, but in AES, the key can be 128, 192, or 256 bits long. Researches consider these key lengths long enough to defeat brute force attempts.

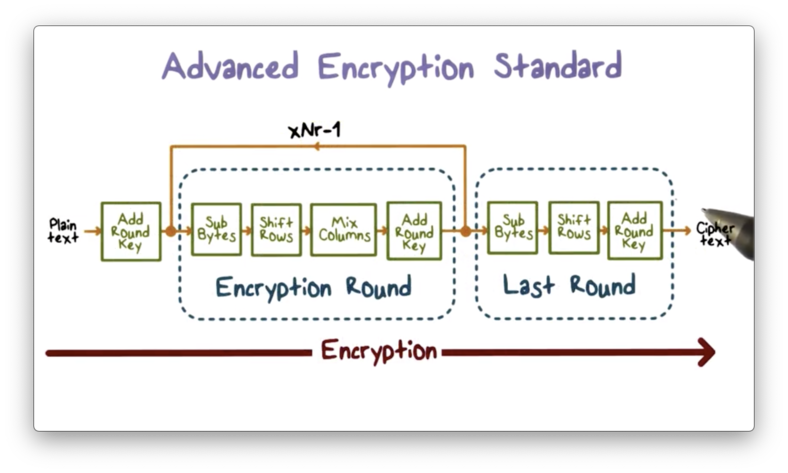

The following diagram presents a high-level overview of AES.

Each block of plaintext that AES operates on is represented as a square matrix called the state array. This array is first XORed with a per-round key before going through multiple rounds of encryption.

In each round, the state array passes through several operations - SubBytes, ShiftRows, and MixColumns - which represent substitution and permutation. The transformed value of the state array is XORed with the per-round key and then passed as input to the next round. The final round, which excludes the MixColumns step, produces the ciphertext.

In AES, the decryption process runs the encryption process in the reverse direction, which means that each of the applied operations must be reversible.

Adding the per-round key involves the XOR operation, which by itself is reversible. The decryption process uses an inverse function to reverse the other operations: SubBytes, ShiftRows, and MixColumns. Since each operation is reversible, the entire process is reversible, and we can recover the plaintext from the ciphertext.

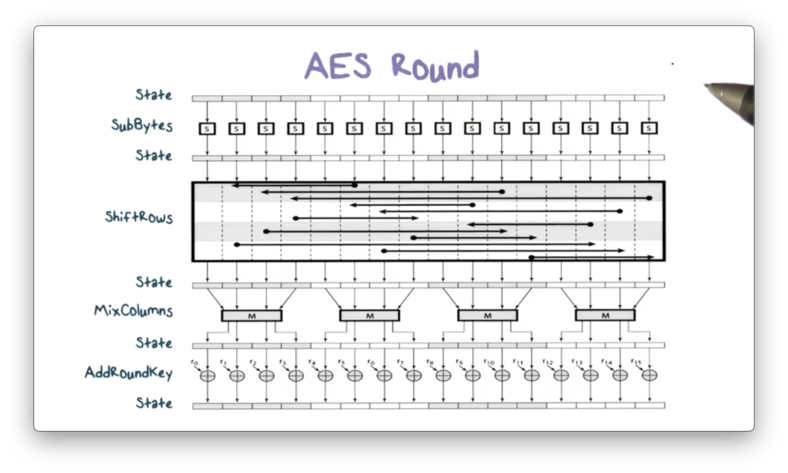

AES Round

Let's take a closer look at each round of AES and the transformations the algorithm performs on the state matrix S. Each operation updates the value of S directly.

First, SubBytes uses S-boxes to perform a byte-by-byte substitution. Next, ShiftRows permutates S by shifting the bytes in each row of S a specified amount. Then, MixColumns substitutes each byte in a column as a function of all the bytes in the column. Finally, AddRoundKey XORs S with the per-round key, passing the final value of S to the next encryption round.

AES Encryption Quiz

AES Encryption Quiz Solution

Encrypting a Large Message

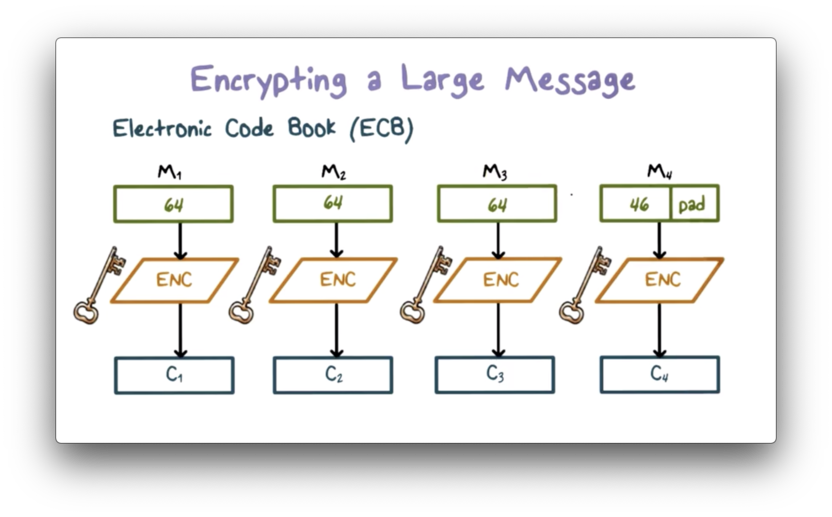

A block cipher takes in a fixed-length data block as input: 64 bits in DES and 128 bits in AES. If we want to encrypt a much bigger message, the solution seems obvious: break the message into fixed-size blocks, apply the cipher to each block, and combine the resulting ciphertexts.

The simplest method for encrypting large messages is to use an electronic codebook (ECB).

First, the original large message is broken down into fixed-size blocks. The final block is potentially padded if it is smaller than the block size. Each plaintext block is then encrypted using the same key, and the collection of ciphertext blocks is the ciphertext of the original message.

For a given key, there is a unique ciphertext block for every plaintext block. We can construct a large codebook - hence the name - in which there is an entry mapping every possible plaintext block to its ciphertext. In practice, the codebook only contains entries for the plaintext blocks used by the application.

ECB Problem #1

There are significant shortcomings with the ECB approach, which make it a weak candidate for ensuring confidentiality.

For a given key, two identical plaintext blocks produce identical ciphertext blocks. As long as the same key is in use, this parity exists within a message and across distinct messages.

Cryptanalysts can exploit this consistency. For example, if an analyst knows that a message always starts with specific predefined fields, then they might immediately have several known plaintext/ciphertext pairs to aid their analysis.

Cryptanalysts can also leverage repetitive elements in a message. Whenever they see two identical ciphertext blocks, they know that the corresponding plaintext blocks are the same.

If they obtain a plaintext block for a ciphertext block, they can be sure that if they see the same ciphertext block again - assuming the key hasn't changed - that it decrypts to the plaintext block in their possession.

ECB Problem #2

Another problem with ECB is that the plaintext blocks are independently encrypted. An attacker can potentially rearrange inflight ciphertext blocks or substitute in a previously captured block for one currently being transmitted. Either way, an attacker can compromise message integrity as a result of the independent encryption scheme used by ECB.

Cipher Block Chaining

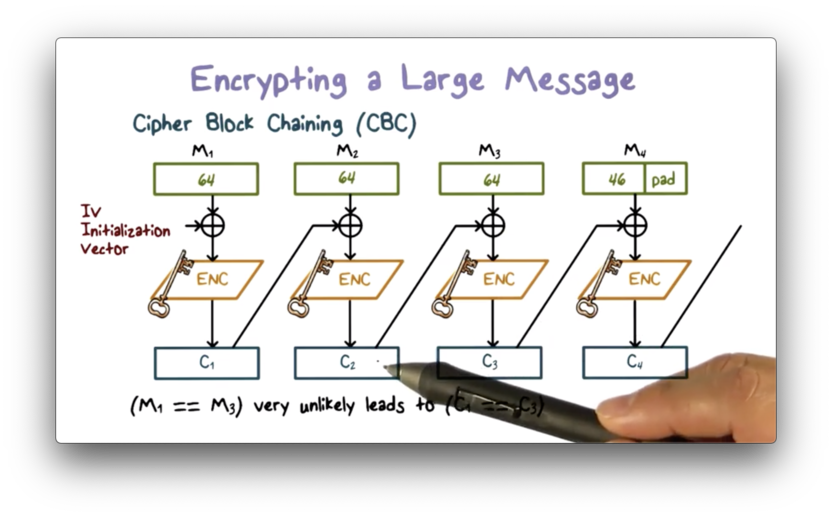

The most widely-used approach for encrypting a large message is cipher block chaining (CBC).

In CBC, the input to the encryption algorithm is the result of XORing the previous ciphertext block with the current plaintext block. To encrypt the first plaintext block, we XOR the block with an initialization vector (IV), which we then encrypt to produce the first ciphertext block.

This process is structured such that each ciphertext block incorporates information from all the previous ciphertext blocks. As a result, determining the plaintext block just by looking at the corresponding ciphertext block becomes very difficult.

More importantly, if two plaintext blocks are the same, the ciphertext blocks are not likely to be the same. Additionally, if an attacker tries to rearrange the ciphertext blocks or substitute one block for another, the ciphertext will not decrypt correctly into the plaintext.

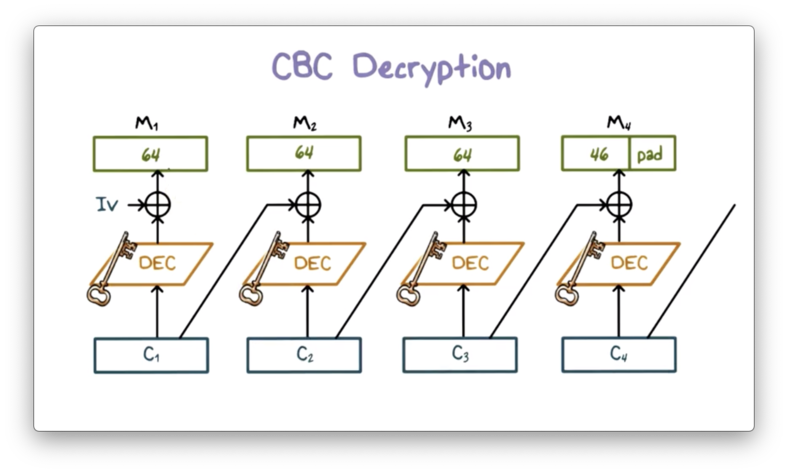

Decryption works similarly. CBC decrypts a ciphertext block and then XORs the result with the previous ciphertext block to produce the current plaintext block.

The first decrypted ciphertext block must be XORed with the IV to produce the first plaintext block, which means that the IV must be known to both parties.

Protecting Message Integrity

While we usually discuss encryption as a method for providing confidentiality, we can also use encryption to ensure message integrity. In other words, encryption can surface unauthorized modifications to messages.

One approach for providing message integrity is to send the last block of CBC - the CBC residue - along with the plaintext. If an attacker intercepts the message and modifies the plaintext, they cannot recompute the CBC residue since they do not have the encryption key. Thus, they are forced to send the modified plaintext with the original residue.

When the authorized recipient receives the message, they will run the message through CBC to produce the residue. Since the plaintext has changed inflight, but the residue has not, the recipient's computed residue will not match the received residue. Therefore, the receiver will know that an unauthorized party has modified the plaintext.

Protecting Message Confidentiality and Integrity

To protect both message confidentiality and integrity, we should use two separate keys and two encryption rounds: one key produces the ciphertext, and the other key produces the CBC residue. Alternatively, we can first compute a hash of the message, append the hash to the message, and then encrypt the entire entity.

CBC Quiz

CBC Quiz Solution

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy