Information Security

Law, Ethics, and Privacy

16 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Law, Ethics, and Privacy

US Laws Related to Online Abuse

People can do many different things online. Some of these activities can be very productive while others can be quite harmful. We can examine the various laws in place that offer protection against different types of online abuse.

For example, consider cybercrime. We know that things like theft and extortion are illegal in the physical world. We've discussed similar activities that take place in the digital realm, such as data theft, identity theft, and ransomware. Thankfully, there are laws that offer us protection against cybercrime just as there are laws that protect us from "real" crime.

Additionally, consider creators of digital objects, such as software or digital music. In the non-digital world, we have ways to protect intellectual property with copyrights, patents, and trade secrets. There is a set of laws that control the copying and distribution of digital objects.

It's important to think about how these laws should be applicable in the context of digital objects. For example, a digital object may be copied and transmitted much more easily than a physical object.

A third area we can think about is our privacy as Internet users. We spend a lot of time online, visiting different websites, using different services, and searching for different things. It's very easy for entities that we interact with digitally to collect a lot information about us. A lot of people worry about the concept of Big Brother watching everything they do, and would like some protection.

Legal Deterrents Quiz

Legal Deterrents Quiz Solution

Cost of Cybercrime Quiz

Cost of Cybercrime Quiz Solution

US Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA)

The first U.S. law related to cybercrime and illegal online activities is the U.S Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). The goal of this act was to define what types of online actions constitute criminal activity and then outline sanctions against those actions.

The CFAA primarily focuses on unauthorized access to computers and the data contained therein. Attackers who break into systems can alter the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of the data on these systems. Additionally, they can tamper with the integrity and availability of the service itself, rendering it unable to carry out its functions on behalf of its user. Since computer systems and computer data are valuable, we would like to protect them from these kinds of activities.

Initially, the CFAA only covered access to computers containing information related to national security and defense. Later, the CFAA extended its scope to include computer systems containing financial information, as many people care about the safety and security of their money. More recently still, the CFAA broadened its scope even further to cover any protected computer: any computer connected to the Internet.

Additionally, the CFAA makes it illegal to distribute malware or other software that allows a user to gain unauthorized access to a computer system.

Finally, the CFAA addresses passwords specifically. Trafficking in computer passwords - selling stolen passwords on the black market - is illegal as well.

Digital Millennium Copyright Act Part 1

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) concerns intellectual property and digital content. The problem it helps to address is piracy - the illegal copying and theft of digital objects.

DMCA says that content creators can copyright their digital objects. As a result, these objects can now receive the same protections as copyrighted objects in the non-digital world.

Additionally, DMCA makes it a crime to circumvent or disable any measures concerning copyright protection and anti-piracy. Not only that, but DMCA also makes it a crime to manufacture and distribute any software or device that can disable anti-piracy protections.

Digital Millennium Copyright Act Part 2

The DMCA does have space for some exceptions, primarily for research and educational purposes. For example, if you are researching the strength and security of an anti-piracy measure, you may need to tamper with that measure deliberately. Additionally, libraries can generally make some limited number of copies of digital objects without being considered in violation of the law.

One of the criticisms that these laws face is that they are too vague and broad, which means that different groups can have different interpretations. On one side, parties like the Recording Industry Association of America have filed suits against entities they believe violated the law, while organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation worry about the broad scope of the laws and the potential for abuse brought on by the laws themselves.

Computer Abuse Laws Enforcement

While the mere presence of laws like CFAA and DMCA is helpful, to a degree, to deter attackers from committing digital crimes, the enforcement of these laws remains challenging for several reasons.

First, connecting malicious computer activity with an attacker can be difficult. For example, an attack may originate from a user's laptop without that user's knowledge at all. Clearly, the user is not to blame; instead, an attacker likely infected their machine with malware or bot code. Because of maneuvers like this, the process of pinning an attack to its exact source can be quite challenging.

To make matters worse, the Internet has no national boundaries. Attackers that digitally cross borders - hacking into a computer in the United States using a computer in Russia, for example - can only be brought to justice through transnational coordination. Many countries are unable or simply unwilling to cooperate with other countries in this context.

Additionally, lawmaking is a slow process, and the stakes are high for focused attackers. As a result, cybercriminals evolve quickly and continue to work around the laws that we put in place. Technology and creativity proceed more quickly than legislation.

Melissa Virus Quiz

Melissa Virus Quiz Solution

Unauthorized Access Quiz

Unauthorized Access Quiz Solution

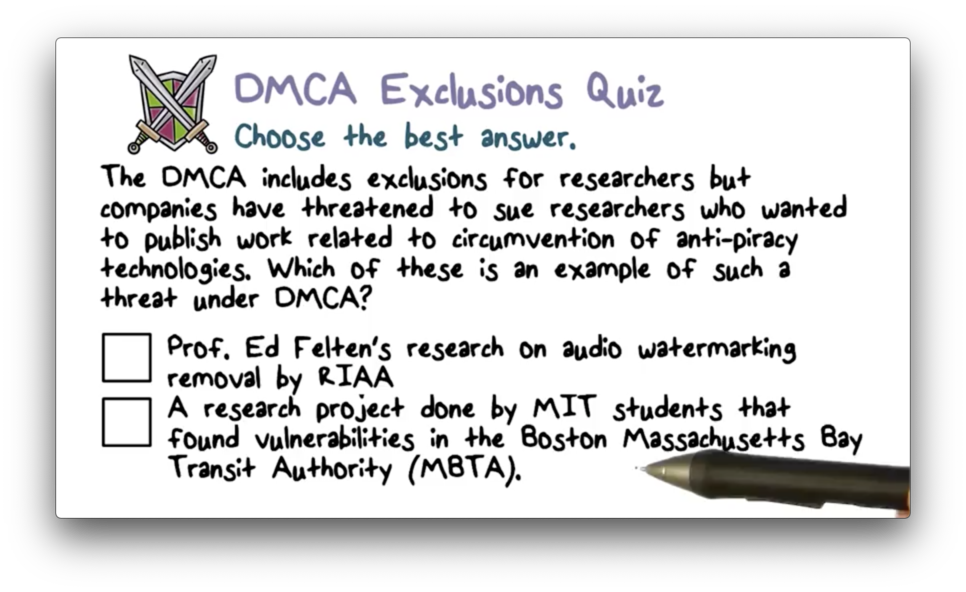

DMCA Exclusions Quiz

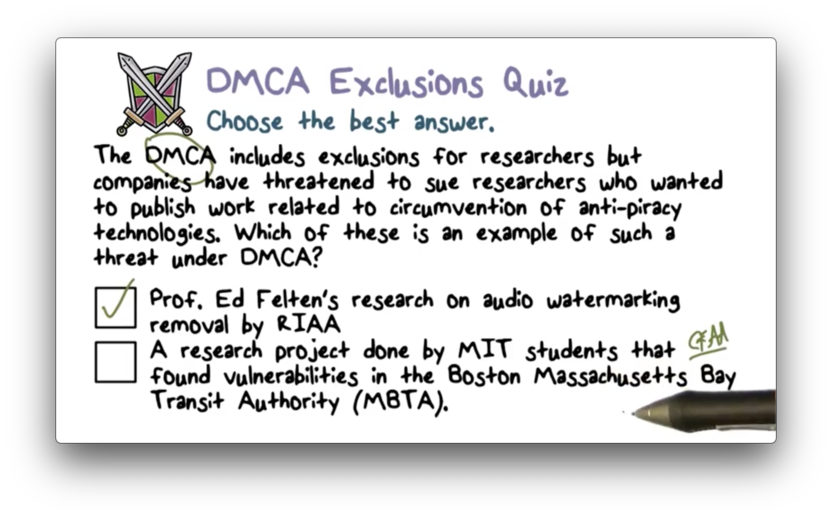

DMCA Exclusions Quiz Solution

Ethical Issues

Laws are manifestations of what we, as a society, determine to be right and wrong. Laws are not subjective on an individual level, and external entities, such as police officers and judges, enforce and arbitrate laws on behalf of society at large.

Ethics are much more personal and help guide our actions based on an internal sense of right and wrong. Something that feels ethical to you might not feel ethical to me. Organizations that we join - ACM, IEEE, or Georgia Tech, for example - may have additional ethical standards or codes of conduct by which they ask us to abide. We stick to our ethics not for fear of going to jail, but rather because they outline what we perceive to be right and appropriate in the world.

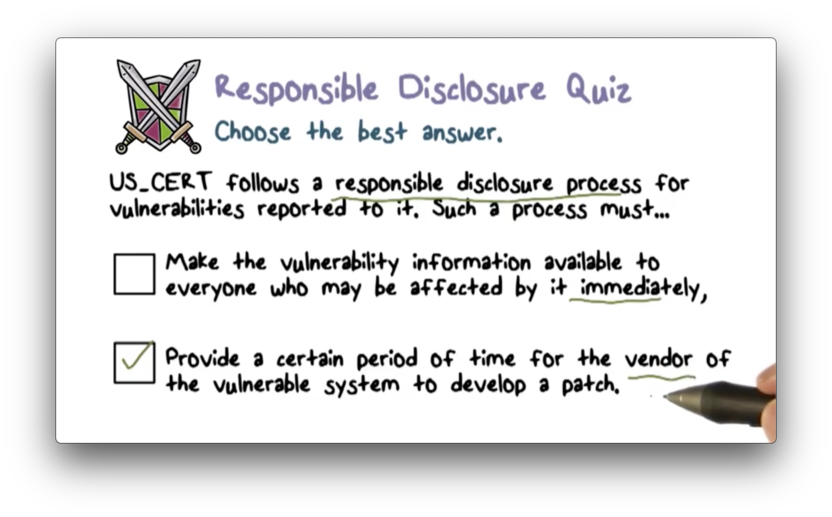

Consider finding a vulnerability in a widely-used software product. What is the ethical disclosure of this vulnerability? On the one hand, public disclosure alerts attackers to the vulnerability. On the other hand, deciding not to disclose the vulnerability removes any motivation for a vendor to fix it. That being said, attackers may have discovered the vulnerability already, so a public disclosure may inform users that they should stop using the software, at least until a patch is out.

Situations like this are present throughout the digital world, and handling them with finesse requires thoughtfulness and a desire to do the right thing.

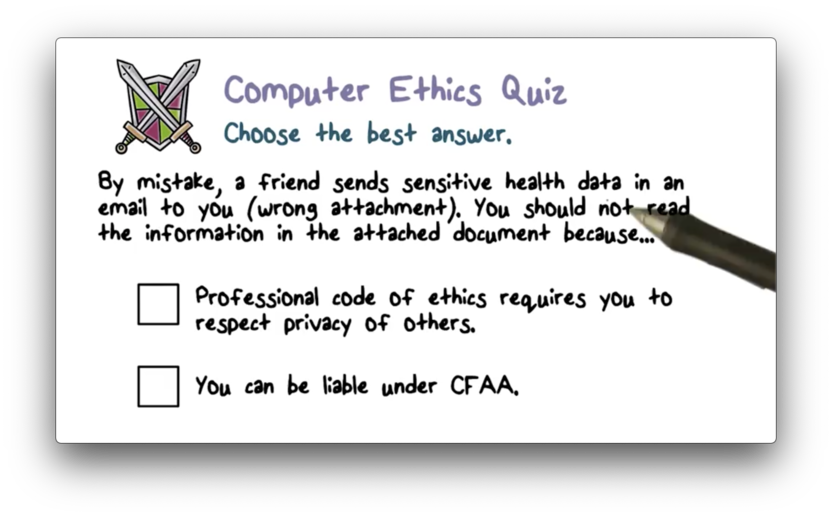

Computer Ethics Quiz

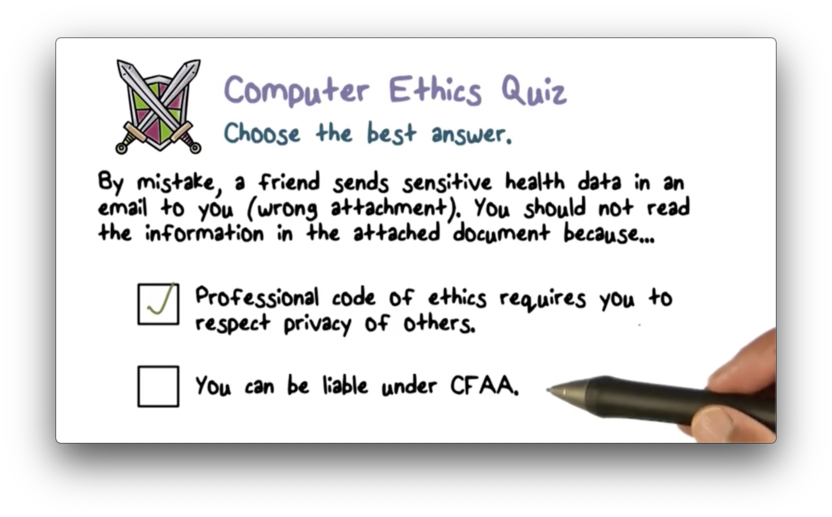

Computer Ethics Quiz Solution

Responsible Disclosure Quiz

Responsible Disclosure Quiz Solution

Privacy Definition

Justice Louis Brandeis made his famous statement about the "right to be let alone" almost 100 years ago; clearly, concerns about privacy are not new. That being said, privacy in the digital era looks different than privacy in the early twentieth century. When we talk about privacy online, we are primarily referring to a user's ability to control how data about him or her is collected, used, and shared by someone else.

Privacy is Not a New Problem

People have always worried about what others - friends, family, adversaries, the government - know about them, whether it be their whereabouts, activities, or preferences. In the modern, digital context, websites and other software capture, use and distribute our information at an unprecedented scale.

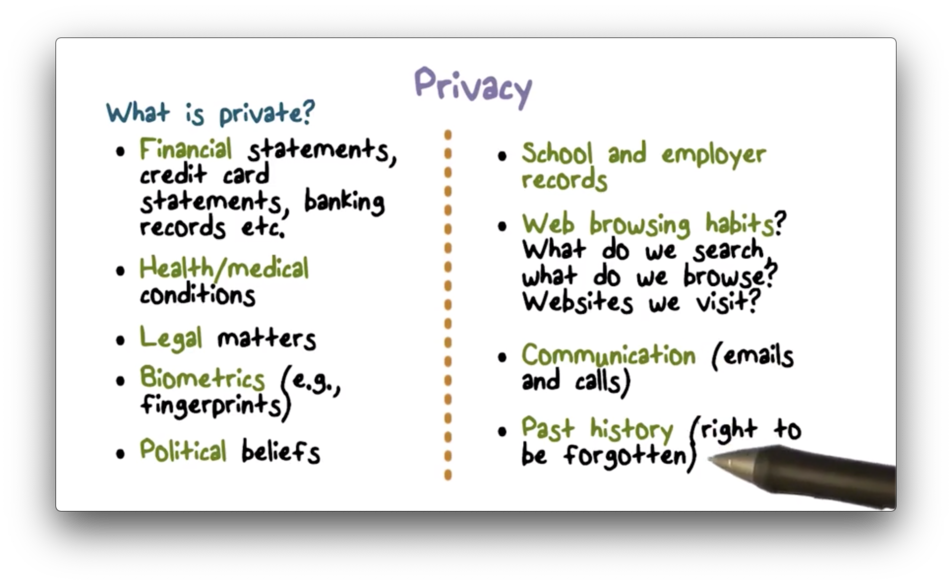

What is Private

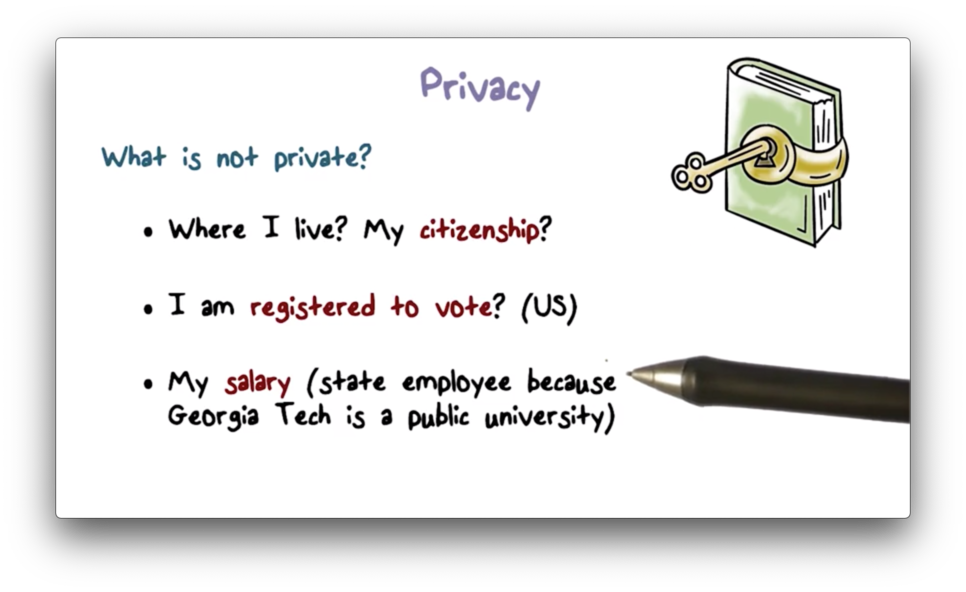

What is Not Private

Institutional Privacy

Privacy refers to the ability of an individual to control the data about them that is collected and shared. Of course, privacy doesn't have to only apply to individuals. Indeed, there may be reasons that universities, hospitals, charities, and even political action committees may want to keep information private.

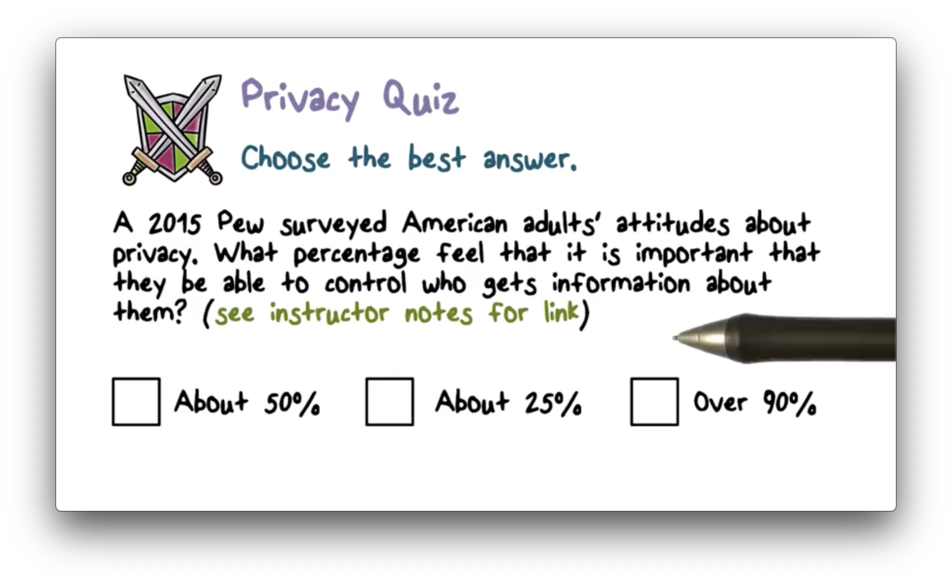

Privacy Quiz

Privacy Quiz Solution

Read more here.

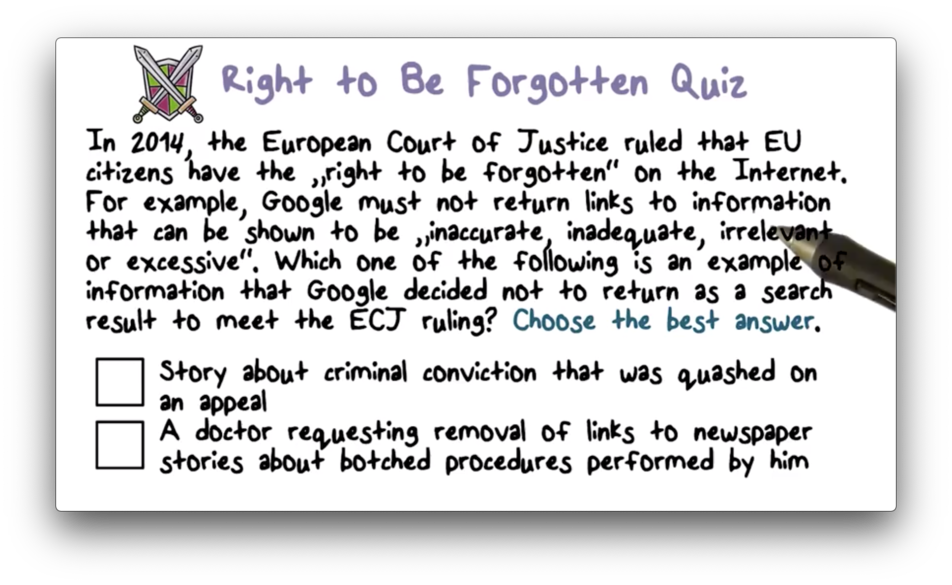

Right to Be Forgotten Quiz

Right to Be Forgotten Quiz Solution

Threats to Privacy Part 1

While we have some idea of what types of information we believe should be private in an online context, we should realize that our desires for privacy are not always respected.

For example, when we talk about network requests from, say, a browser to a server, we have to understand that our communication must pass through the greater Internet. While people generally believe that information regarding which websites they visit should be private, traffic sniffing and analysis are threats to that belief. An attacker who observes the packets sent between you and a website can violate the confidentiality of this information.

Additionally, large scale surveillance is a threat to privacy. Some law enforcement officials claim that allowing encryption without providing a backdoor allows criminals to communicate in complete secret, while others argue that we are currently in the golden age of surveillance. Every piece of information about us is tracked and collected.

Finally, it may be possible for others to infer information about us, even if they don't possess it directly. For example, when we talked about database inference attacks, we discussed how different data setups, combined with public information an attacker already has, make it easy to de-anonymize data about specific individuals. In the world of big data and data mining analytics today, these inferences are becoming more common.

Threats to Privacy Part 2

Social media poses a threat to privacy, as well. While we use these social sites as a tool for communicating with our friends and sharing with the people around us, we also share all of the information we create with companies like Facebook and Twitter.

Additionally, web tracking serves to reveal information about our browsing habits. Obviously, when we visit a web site, the owner of that site knows that we visited, but the owner can also choose to pass that information along to third parties for analysis. For example, an e-commerce site may let Google know that you visited so that Google can serve you an advertisement for the site later on.

Finally, we enable this behavior. We frequently pass over our information to vendors - whether our name, phone number, or email address - for small discounts in the form of digital coupons and loyalty program memberships. We violate our own privacy, in a sense, by feeding information into a system that we know is designed to exploit us.

Privacy Threats to Online Tracking Info

One threat to privacy in the context of online tracking concerns information collection. Many of us are aware that certain websites and services collect information about us because most platforms require us to agree to such collection. If companies did not tell us they were collecting information about us but did it regardless, we might consider them to be invading our privacy.

Once a company has our information, we might be concerned with how they use it. Information is powerful, and a company that does not disclose how they use the information they collect might wield it in a way that invades our privacy.

Additionally, we might be curious as to how long a company might keep such information. People change, and information that was valid at one time in the past may not be valid in the present.

Perhaps a company has all the best intentions with our data. We might not be worried about them specifically, but we might want to examine their business partners and other entities with whom they share data. These partners may not use best practices for keeping our data safe from attackers, and the entities that they partner with might be even less professional.

A company may specify all of these factors - what data they collect, what they do with the data, how long they keep the data, and with whom they share the data - in a document known as a privacy policy.

Indeed, the privacy policy itself can serve as a threat to privacy. Imagine reading and agreeing to a policy that later is changed to be much more lax concerning data collection, use, and distribution. A privacy policy that can change at any time, to any degree, without subsequent consent, is as bad as no privacy policy at all.

Finally, we also have to consider the security implications of collecting and storing all of this information. Since attackers have no regard for privacy and consent, we can assume that they will treat our data in the worst way possible. Companies need to address how they safeguard our data even in the face of theft.

Example: Google Privacy Policy

While most websites have privacy policies, few of us honestly look at them carefully, if at all. Let's look at some components of Google's privacy policy.

Some information that Google collects about us is the information that we give it. For example, when we create a new account in Gmail, we likely provide our name, alternative email address, and phone number.

Other information is collected less visibly. When we visit certain websites or use Google services, it can record the actions we perform and the content we consume.

Google uses cookies - a general website-based tracking mechanism - to keep various pieces of state on our browsers as we move about the internet. As a result, Google can collect information about us even when we are not connected to a particular Google service at the moment.

Additionally, Google captures information about the device we use to communicate with their services. For example, when our browser connects to Gmail, it passes along information such as our operating system, our IP address, and network information.

Google's original killer feature was search, and so Google naturally collects and retains your search queries to understand what kind of information you are interested in consuming.

If you use Google Voice, Google has information about who you call and how long you talk. Additionally, some Google services may collect location information.

Google: How is Info Used

We saw how Google collects information about us, and what type of information it collects, so now we have to ask how Google uses that information. Google has two primary uses for the data it collects about us.

First, it uses the data to personalize our experience with its services. Two random people are likely interested in quite different types of information, and the more information that Google has about them, the more it can tailor an experience to them.

For example, a doctor searching for "lens" might be referring to the part of the eye, while a photographer might be looking for the part of the camera. Without collecting (or inferring) the occupation of both searchers, Google might serve the same search result to two contextually different queries.

Second, Google uses the data to serve better-targeted advertisements. Google makes its money selling ads and, the more it knows about you, the better it can understand which products and services you are likely to buy. This knowledge allows it to charge a higher premium for ad delivery using its network.

Google: Who is it Shared With

Now that we understand how Google collects and uses our information, we can begin to look at how and with whom Google shares our information.

Google allows us to opt-in to sharing our information with other businesses and services. For example, if we use a "Log in with Google" button on a third party website, Google makes us confirm that we indeed consent to give this third party our information.

Additionally, Google may share information with individuals who provide user support to an organization to which we belong. These individuals include, for example, domain administrators and resellers. Google also shares information with affiliates, which are other trusted businesses or people.

Finally, Google can share the information with the government for legal reasons, and it has improved its transparency in recent years concerning what kind of information it shares with the government or law enforcement.

Google: Information Security

Our conversation would not be complete without an examination of the security regarding our information and privacy.

Many Google services use HTTPS for encryption of data transmission, as well as encryption for data persistent on their servers. Additionally, Google requires two-factor authentication and makes you enter your password and a token before giving you access to your account on a new device.

Google also provides transparency around changes to its privacy policy. Basically, its stance on privacy policy changes is that you have to explicitly consent to any changes that may reduce your rights concerning your privacy. In other words, any changes that make the privacy more lax require your agreement before those changes go into effect with your data.

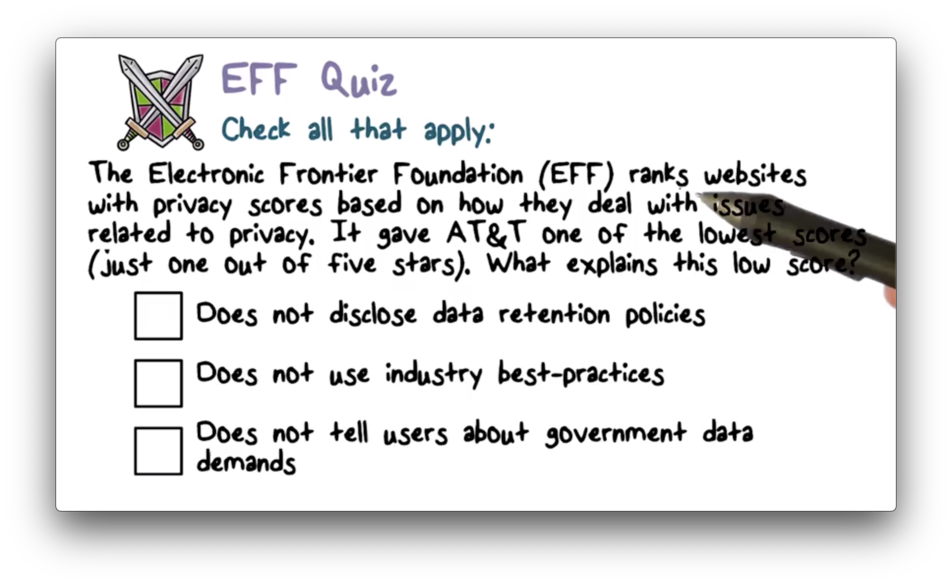

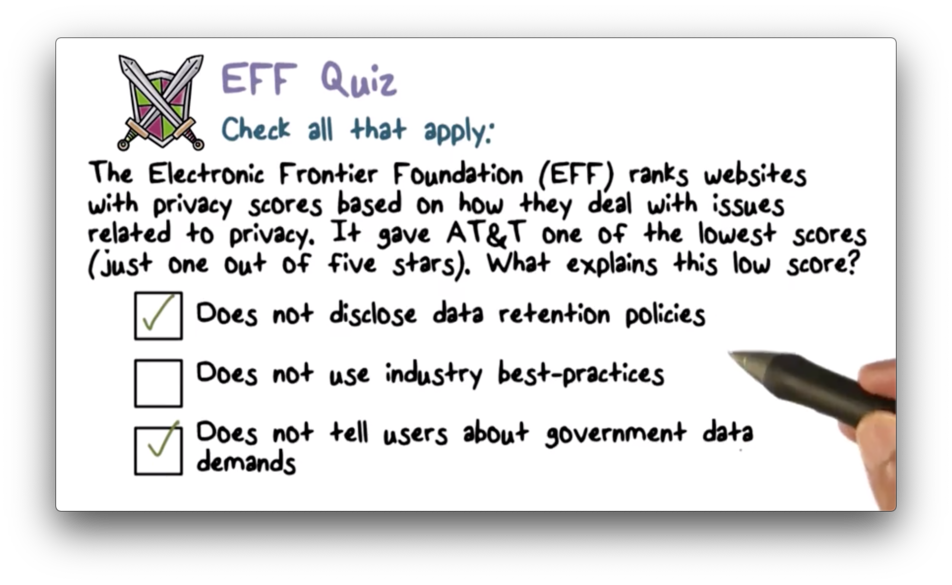

EFF Quiz

EFF Quiz Solution

Read more here

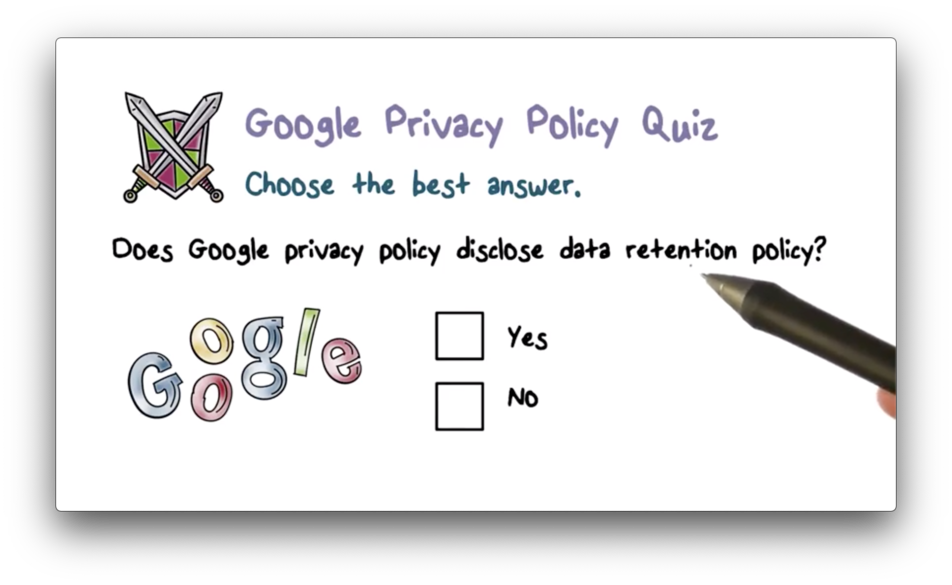

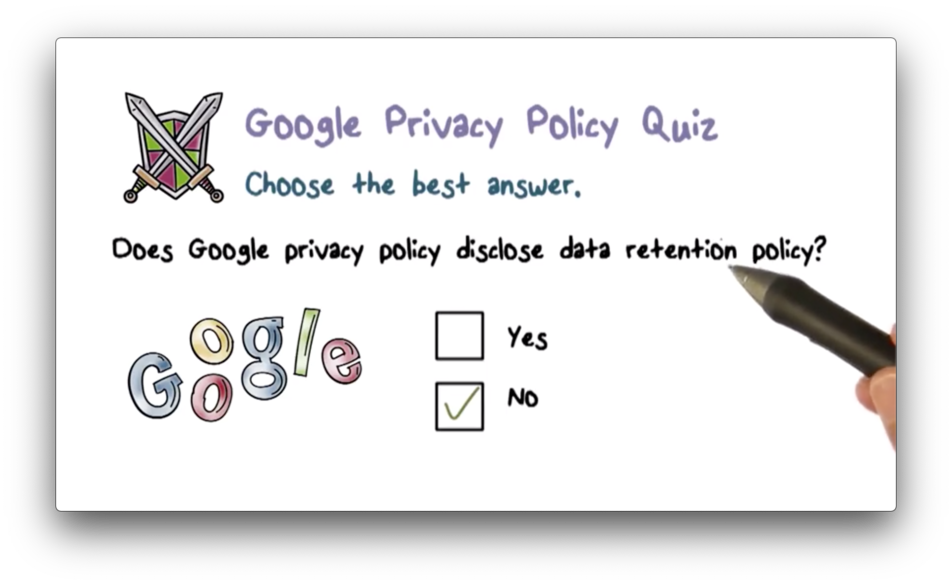

Google Privacy Policy Quiz

Google Privacy Policy Quiz Solution

Legal Deterrents Quiz

Legal Deterrents Quiz Solution

Facebook Privacy Policies

Now that we have discussed what a particular privacy policy might address, we can talk about how well a company adheres to its policy. For this example, we are going to look at Facebook.

Facebook has not done a good job of sticking to its privacy policy. In fact, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) had to step in to make sure Facebook stopped doing things with user's information without their consent.

Facebook did numerous things that violated the privacy of its users. For example, it made information that users had designated as private, particularly regarding friend lists, public without their consent.

Additionally, Facebook made personal information available to applications of friends, which means that a friend could access information through an application that a user didn't agree to share.

Furthermore, Facebook shared information with advertisers that they had promised not to share. Finally, Facebook said that certain applications were verified when they were not verified, thus misleading users.

As a result, the FTC has taken action against Facebook and mandated that it acts in specific ways to rectify the situation.

For example, Facebook now has to undergo a third-party privacy audit every two years for the next twenty years. The FTC has decided that it cannot take Facebook's word concerning privacy, and so a third party must independently verify that Facebook is doing the right thing.

Additionally, Facebook is prohibited from misrepresenting privacy and security settings provided to its users. If they say something is not public, it should not be public.

Finally, the FTC also requires that Facebook gets consent from users before sharing any information in a way that exceeds their privacy settings.

Essentially, consent is the focal point when it comes to privacy. If you give express, affirmative consent to a particular action, a company can perform that action. Since Facebook did not get consent before using users' information, the FTC had to impose sanctions on them.

Privacy Enhancing Technologies

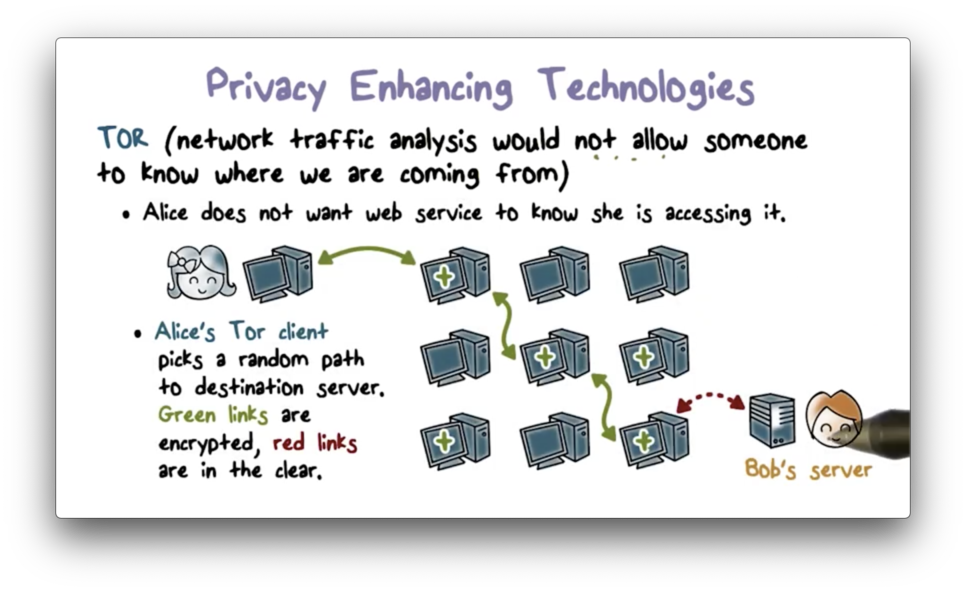

We've talked about how privacy is a good thing, so now let's examine some of the tools and technology we can use to enhance our privacy online.

One of the privacy threats that we discussed was traffic analysis. Through traffic analysis, attackers can understand who is talking to whom by looking at the source and destination information embedded in a packet.

If we don't want anyone to see this information, we can use a technology called TOR. Using a TOR client, a user can route their traffic through a random path of TOR nodes to their destination. Each node only knows its immediate predecessor and successor and cannot tell where a packet originated or where it is ultimately headed.

Because of this setup, we can use TOR to implement anonymous communication and prevent attackers from learning about the parties with whom we communicate.

TOR

Now that we've taken a brief look at The Onion Router (TOR) let's dive deeper into how it works and what services it can provide to us.

First, a TOR client uses a directory service to get a set of TOR nodes that can help us route a message from point A to point B. The client picks some random subset of the nodes and orders them. This order forms the path that the traffic traverses as it passes from A to B.

Next, the client encrypts the message as follows. It first encrypts the message with the public key of the final node. Then, it encrypts that result with the public key of the second to last node. It works backward until it finally encrypts the bundle with the public key of the first node.

This strategy results in a message that is encrypted in layers, hence the "onion". As the traffic passes through the network, each node decrypts its layer, unwrapping the message one decryption at a time. The final node reveals the plaintext packet and forwards it the last hop to its destination.

Controlling Tracking on the Internet

Browsers give us some control with regard to how we are tracked on the Internet. There are a few techniques we can employ to try to reduce the amount of information collected about us.

For instance, we can block third-party cookies. When we visit a site like newyorktimes.com, it can place cookies on our browser. Additionally, it can embed content from other third-party sites, like Facebook, Twitter, and Google, and those sites can also place cookies in our browser. By blocking third-party cookies, we reduce tracking to just the site that we are currently visiting.

Additionally, you can tell your browser that you don't want to be tracked. Many browsers allow you to set flags like this, and they pass that information along to the websites that you visit. Whether the website honors the request is a different story.

You can also delete your cookies periodically, block popups, and use private browsing. Each of these activities helps to reduce the amount of information an entity can capture about you.

Fandango Quiz

Fandango Quiz Solution

Tracking Quiz

Tracking Quiz Solution

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy