Information Security

Hashes

11 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Hashes

Hash Functions

A hash function can be applied to a block of data of any size and produces a fixed-size output, typically in the range of 128-512 bits. Given a message , computing the hash should be very easy.

These properties make hash functions practical for security applications. We need our hash functions to be able to handle arbitrary input and compute their output efficiently.

The following properties are required for hash functions to be secure.

One-Way Function

Given , it should be computationally infeasible to find . We call such a non-invertible function a one-way function.

Alice can authenticate a message by hashing a secret value and appending it to the message. If an attacker intercepts this message and the hash function is not one-way, then the attacker can find the input that computes the hash value. That is, the attacker can invert the hash function to obtain the secret value from its hash.

Weak Collision-Resistant Property

Given input data , it should be computationally infeasible to find another input value , such that . This property of hash functions is the weak collision-resistant property.

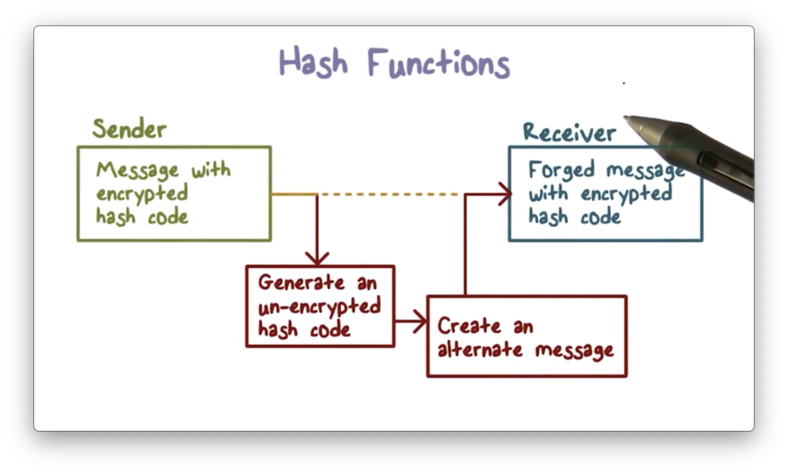

Suppose that Alice wants to send a message to Bob, and she wants to ensure that the message arrives to him unmodified. She can create an encrypted hash of the message and send both the message and the hash to Bob.

When the attacker intercepts the message and encrypted hash code, they can recompute the (unencrypted) hash code of the message. If the weak collision property is not present, then the attacker can find another message such that the hash value of that message is the same as the hash value of the original message.

Even though the hash code is encrypted, the attacker only needs to find a message that reproduces the unencrypted hash code, since the encryption of two identical hash codes produces the same result.

As a result, the receiver is unable to tell that an attacker has modified the message because the modified message has the same hash code as the original message, and thus the same encrypted hash code.

Strong Collision-Resistant Property

The strong collision-resistant property states that it should be computationally infeasible to find two different inputs , such that .

The strong collision-resistant property implies the weak collision-resistant property; that is, while the latter only requires that a hash function is collision-resistant regarding a specific input message, the former requires collision resistance for any pair of given messages. Thus, a hash function cannot meet the strong collision-resistant property without also satisfying the weak collision-resistant property.

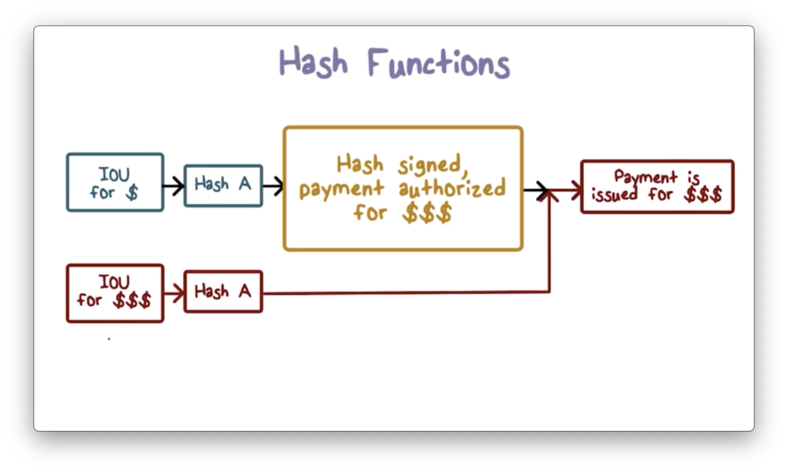

Suppose that Bob does some work for Alice, and he wants her to pay him later. He can draft an IOU message and ask Alice to digitally sign it as a way of agreeing to pay it. To sign the IOU, Alice first hashes it and then signs the hash using her private key. Later, Bob can present this IOU message, along with the signature, to Alice or Alice's bank to retrieve the payment.

If the strong collision-resistant property is not present, Bob can find two different messages that have the same hash code: one requesting Alice to pay a small amount , and another requesting her to pay a more substantial amount .

Bob can present the IOU for to Alice and have Alice sign it. Later, Bob can present the signature with the message for and ask Alice to pay it. Because the two messages have the same hash value, Alice cannot deny that she has signed the message agreeing to pay .

Hash Function Weaknesses

To understand the constraints and potential weaknesses of hash functions, we need to understand two concepts: the pigeonhole principle, and the birthday paradox.

Pigeonhole Principle

Imagine we have nine pigeonholes. If we have nine pigeons, then we can place each pigeon in one hole. Generally, for pigeons and holes, each pigeon can occupy an unoccupied hole when .

If we add another pigeon, then there must be one hole occupied by two pigeons. Generally, if , then at least one hole must have more than one pigeon.

Birthday Paradox

How many people do you need in a room before you have a greater than 50% chance that two of them have the same birthday?

There are 365 birthdays, and we can think of these birthdays as pigeonholes. Then, the probability that two people in the room have the same birthday is the probability that two people occupy one pigeonhole.

Obviously, with 366 people, there is a 100% chance that two people have the same birthday.

If we only want a good chance, say 50%, that two people share a birthday, how do we calculate how many people we need in the room?

We can reframe the problem to ask instead: how many people do we need in a room before the probability that everyone has a unique birthday drops below 50%?

When we place the first person in the room, . Since there are no other people in the room, is guaranteed to have a unique birthday.

When we place the second person in the room, there are only 364 unique days left, since has already taken one day. The probability that doesn't share 's birthday is , and thus the overall probability drops from 1 to .

The third person, , is in a similar situation. Since two people precede them, there are only 363 available birthdays left. As a result, drops to . We multiply the probabilities because we need to make sure that doesn't violate the uniqueness constraint and doesn't either. Technically, this is a conditional probability.

Generally, for possible birthdays and individuals in the room, we can calculate the as:

p = (1 / k)^n * (k! / (k - n)!)We can steadily increase to determine when dips below 0.5. For and , we see that:

p = (1 / 365)^23 * (365! / (365 - 23)!) = 0.492703Since is the probability that no birthdays overlap, the probability that one or more birthdays overlap is .

Analytically, the probability of repetition given possible events and selected events, is approximately . This probability is 0.5 when . For example, if , then approximately, which is close to the correct answer of 23.

Back to Hash Functions

Once we understand the pigeonhole principle and the birthday paradox, we see that some of the properties of hash functions seem to contradict each other.

Remember, a hash function produces a fixed-size output from an input of arbitrary size. Since there are an infinite number of arbitrarily-sized inputs, and a finite number of fixed-size hash codes, many inputs can be mapped to the same output hash value. In other words, we have many more pigeons than pigeonholes.

This setup seems to violate the property of collision resistance. However, the collision resistance properties only speak to computational infeasibility, not mathematical impossibility. From a security perspective, a collision that is infeasible to find is as good as one that doesn't exist.

The larger the number of output hash values, the harder it is to find a collision. We can reduce the probability of a collision by increasing the length of the hash code.

Determining Hash Length

To reduce the chance of collision, we need to use hash functions that produce longer hash values, but how many bits is enough?

Suppose a hash function produces hash codes that are bits long. As a result, this function can produce possible hash values. According to the birthday paradox, we have a 50% chance of finding a collision after processing messages.

Therefore, if , then there are hash values, and an attacker only needs to search messages to find a collision. This search is entirely feasible with modern computing power. In practice, hash values are at least 128 bits long.

Hash Size Quiz

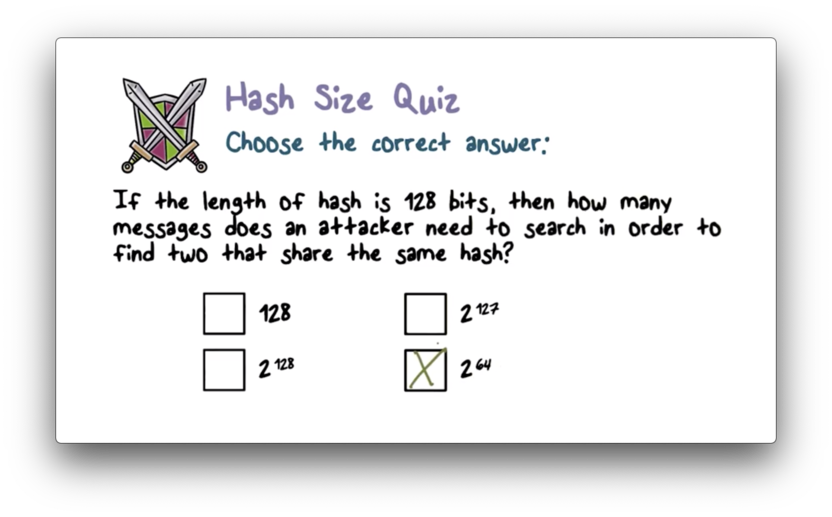

Hash Size Quiz Solution

Given a hash length , an attacker needs to hash messages to find a collision. For , an attacker needs to compute hashes.

Secure Hash Algorithm

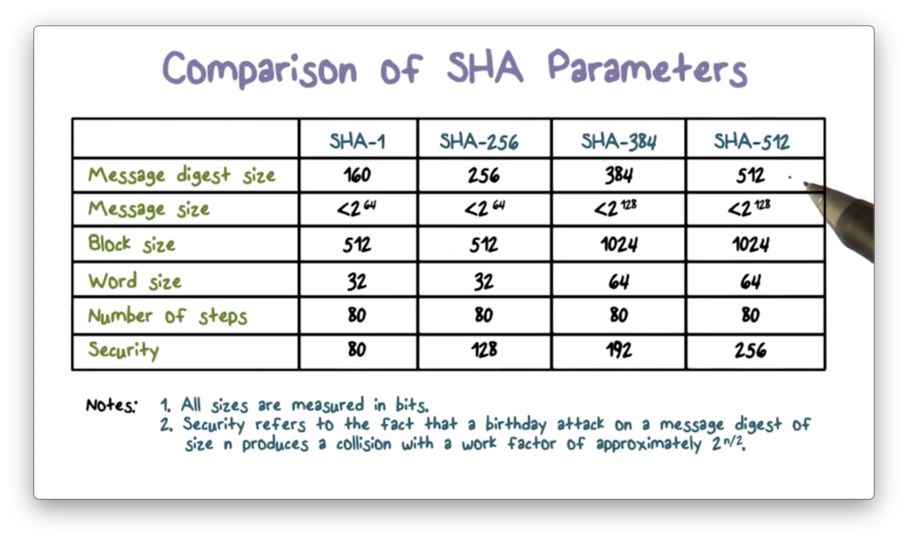

The original secure hash algorithm is SHA-1, which produces a hash value of 160 bits. The subsequent SHA-2 family of algorithms, which operate similarly to SHA-1, produce hashes of 256-, 384-, and 512-bits long.

The following table compares the SHA parameters.

Message digest size refers to the length of the hash value. As we know, SHA-1 produces 160-bit hashes, and SHA-512 produces 512-bit hashes.

Message size is the size limit on the input. These limits do not have any effect in practice, because most, if not all, messages are much smaller. For example, SHA-1 caps the message size at 2^64 bits. Given that one terabyte is 2^43, SHA-1 can hash a message that is over two million terabytes long.

As we move from left to right in the table, each subsequent algorithm produces a hash value with more bits. Consequently, each subsequent hash function is more secure than the last. For example, with a hash value size of 160 bits, the search space for an attacker to find a collision with SHA-1 is 2^80 messages. For SHA-512, that search space grows to 2^256 messages.

Message Processing

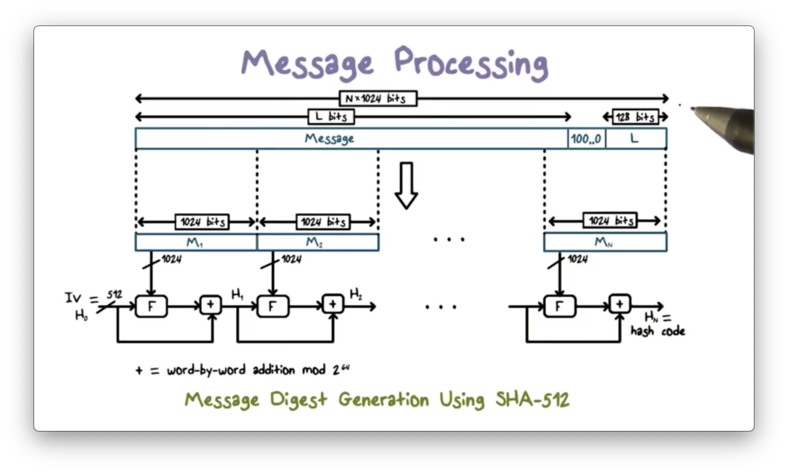

The following figure shows the overall processing of a message to produce a hash value.

Before any processing can start, we must pad the message to a multiple of 1024 because the hash function processes the message in 1024-bit blocks. First, we store the length of the original message in the final 128 bits of the last block. Next, we fill in the space between the end of the original message and the last 128 bits with 1 followed by as many 0s as necessary.

After padding, the message is processed one 1024-bit block at a time. The output of processing the current block becomes the input to processing the next block. That is, when processing the second block, the input includes not only the second message block but also the output of the processing of the first message block.

For the first message block, the input includes an initialization vector (IV), a 512-bit value hardcoded in the algorithm.

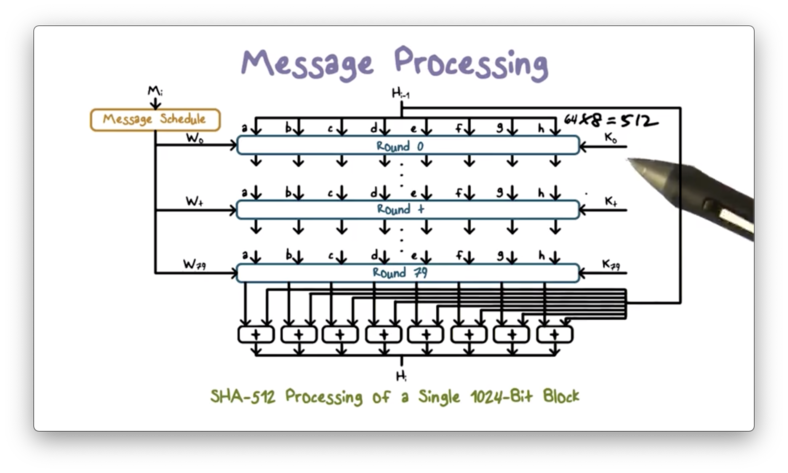

The following figure shows the processing of a single message block.

Processing a single block involves 80 rounds of operations that operate on both the current message block and the output of processing the previous block.

The inputs to each round include the result from the previous round, some constant , and some words derived from . provides randomized values to eliminate any regularities in .

The operations at each round include circular shifts and primitive boolean functions based on AND, OR, NOT, and XOR.

The result of processing the current block becomes input for processing the next block, and the result of processing the final block is the hash code for the entire message.

Hash Based Message Authentication

Using hash values for message authentication has several advantages. For example, hash functions are very efficient to compute, and libraries for hash functions are widely available. On the other hand, a hash function such as SHA cannot be used directly for message authentication because it does not rely on a secret.

There have been several proposals to incorporate a secret key into an existing hash function. HMAC has received the most support thus far and has been adopted for use in other protocols such as IPSec and TLS.

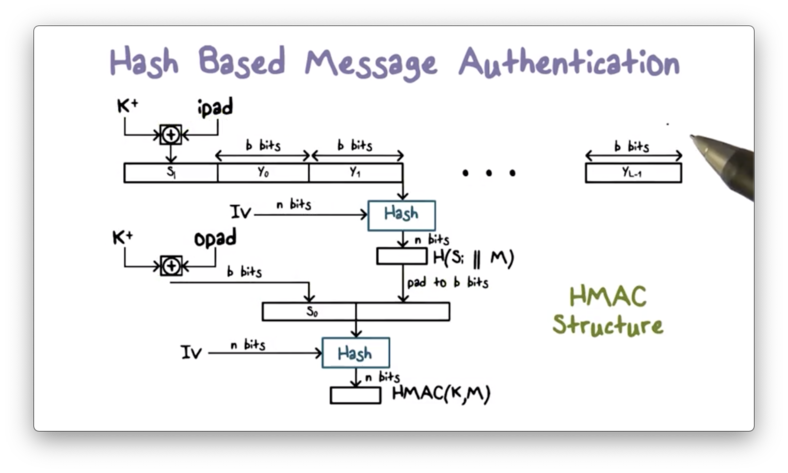

The following diagram illustrates how HMAC works.

HMAC involves a hash function and a secret key . The message consists of multiple blocks of bits. For example, in SHA-512, each block is 1024 bits, so .

First, is padded to bits, which is accomplished by appending zeroes to . The padded key is then XORed with , a constant designed to eliminate any regularities in the key.

The result is a -bit value . is prepended to , and then the combination is hashed using to produce an -bit hash value. For example, if the hash function is SHA-512, then .

Next, the -bit hash value is padded to bits. The padded key is then XORed with , another constant designed to eliminate regularities in the key. The result is a -bit value .

The padded hash is then appended to , and the entire message is hashed. The -bit result is the output of the HMAC procedure.

HMAC Security

The security of HMAC depends on the cryptographic strength of the underlying hash function. For HMAC to be secure, the underlying hash function must satisfy the properties of non-invertibility and collision resistance.

Furthermore, compared with a cryptographic hash function, it is much harder to launch a successful collision attack on HMAC because HMAC uses a secret key.

For example, suppose the attacker obtains the HMAC of message and wants to find another message such that .

Without the secret key, there is no way the attacker can compute the correct HMAC value for . Thus, the attacker can't determine whether and have collision in HMAC.

In summary, because of the use of the secret key, HMAC is much more secure than a cryptographic hash function alone.

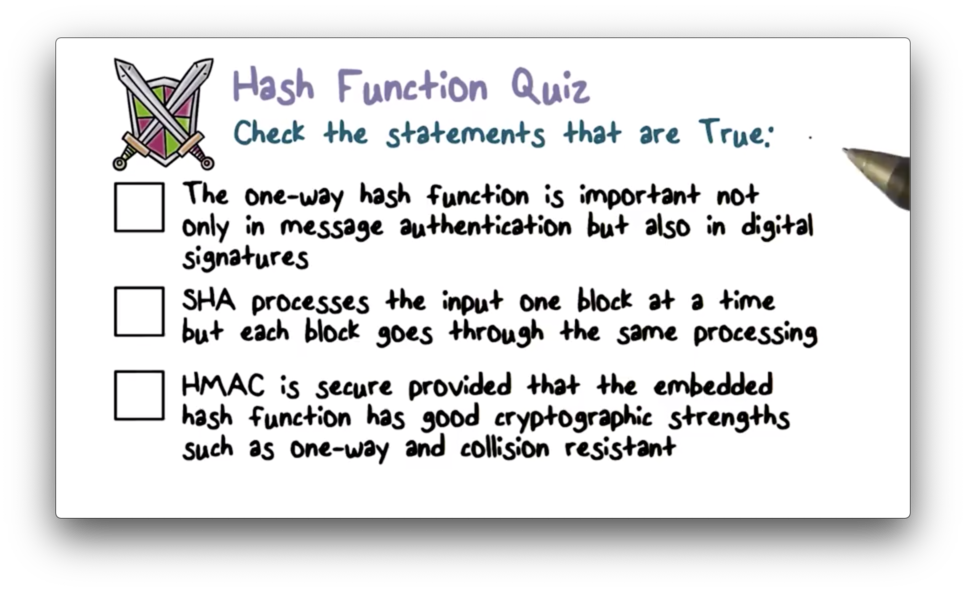

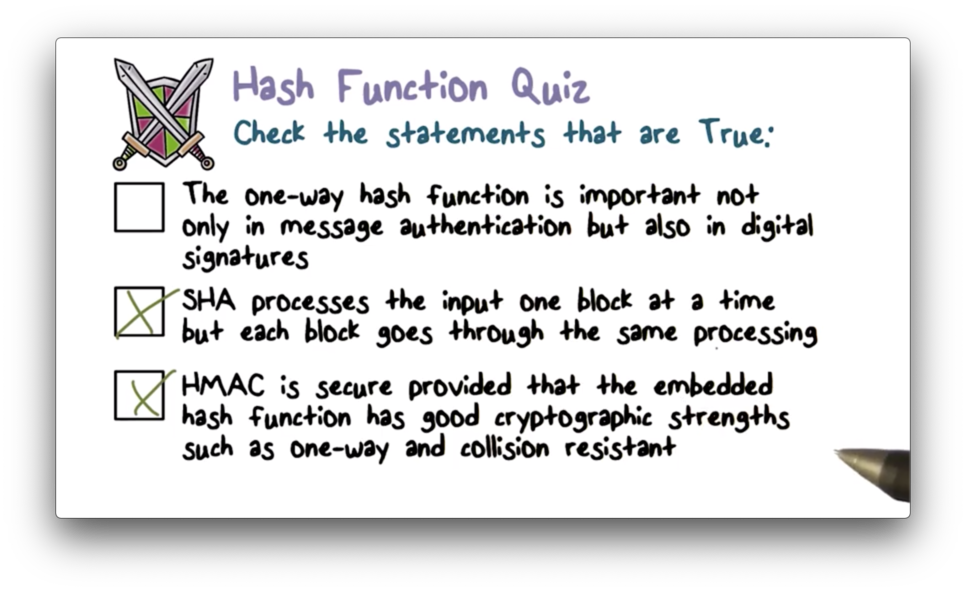

Hash Function Quiz

Hash Function Quiz Solution

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy