Information Security

Access Control

14 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Access Control

Controlling Accesses to Resources

Any program can make a request for a protected resource, so the OS needs to know whether to grant or deny these requests.

For example, if John is a student in a class, and he makes a request to read a file containing the grades for all of the students in that class, should his request be granted?

Remember, authentication tells us the user on whose behalf a process or application makes a request. Authentication allows us to know that the above request came from John.

Authorization, or access control, involves determining if a certain requestor is allowed to access the resources they are requesting in the manner in which they are requesting. Access control determines whether John can access the file for reading or not.

Resources - like files - that we have in the system are created by certain users, or subjects.

One implementation of access control says that the creator of a resource has full reign over how that resource is accessed.

Indeed, in many systems the idea of a resource owner is defined, and it can be at the discretion of the owner how that resource can be shared.

Of course, there are situations where this is not true. For example, your company may not allow you to decide how you wish to share information related to that company, regardless of whether you created the information or not.

Access and Authentication

In order to understand whether a resource access request should be granted or denied, we need to know who is allowed to access which resources in a given system.

There are two components to the problem of access control.

First, system administrators need to specify who has access to what. This specification is called an access control policy.

Once the administrators have delivered this policy to the system, the system needs to monitor each request and ensure that any accesses it grants are consistent with the policy.

Complete mediation is essential for access control to work. There is no point having a system enforce policies if a user can step around the system.

Access Control Matrix Defined

We can abstract the information about "who has access to what" into a data structure called an access control matrix (ACM).

Like any matrix, an ACM has rows and columns. The rows of an ACM correspond to the users, subjects or groups present in the system. The columns of an ACM correspond to the system resources that need to be protected.

Each cell in the ACM, indexable by user and resource, contains a set of operations that the queried user can perform on the queried resource.

For example if we have an ACM A, a user U, and a resource R, then A[U,R] contains the list of operations that U can perform on R.

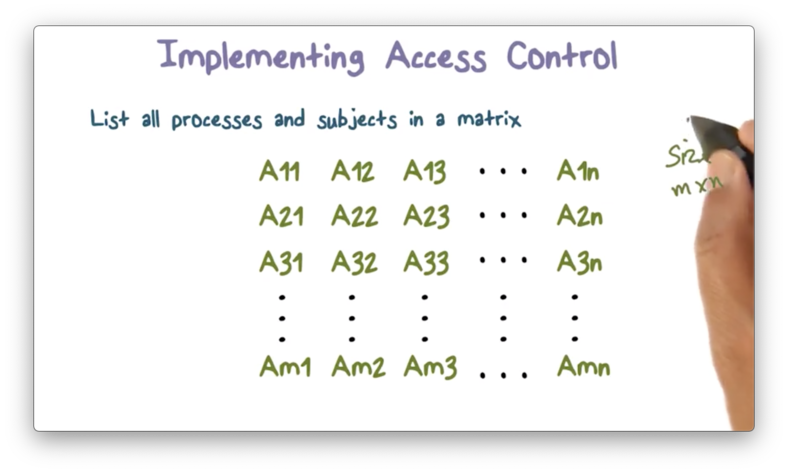

Access Control Matrix

Here is an example of an m x n matrix, with m rows and n columns.

The first row in this matrix corresponds to the first user, the second row to the second user, and so on until the m-th user in the m-th row.

Likewise, the first column in this matrix corresponds to the first object, the second column to the second object, and so on until the n-th object in the n-th column.

Each cell in this matrix contains the authorized operations that a user can perform on an object. For example, the cell at A[3,2] contains the operations that user three can perform on object two.

The operations present will be some subset of the possible operations that can be performed on the given resource. In the case of a file F - which can be readable, writeable, and/or executable - and user U , A[U,F] will have some combination of read, write, and execute bits present.

Data Confidentiality Quiz

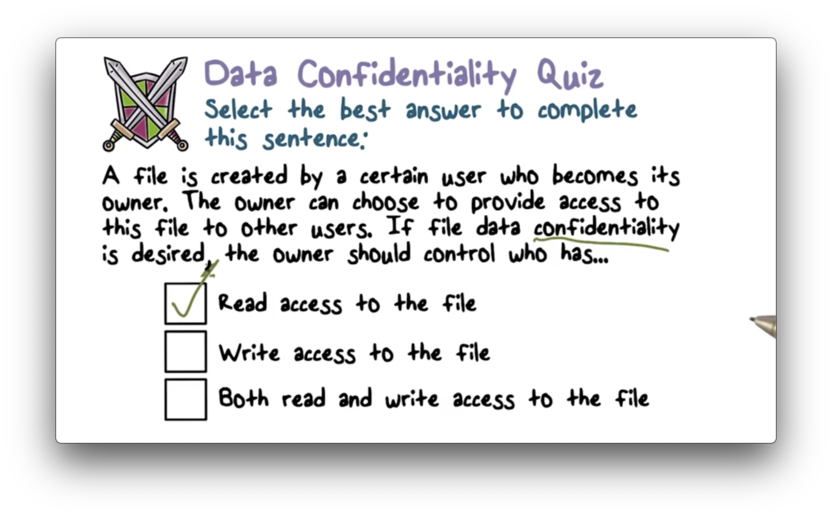

Data Confidentiality Quiz Solution

Controlling read access is connected to data confidentiality, while controlling write access is connected to data integrity.

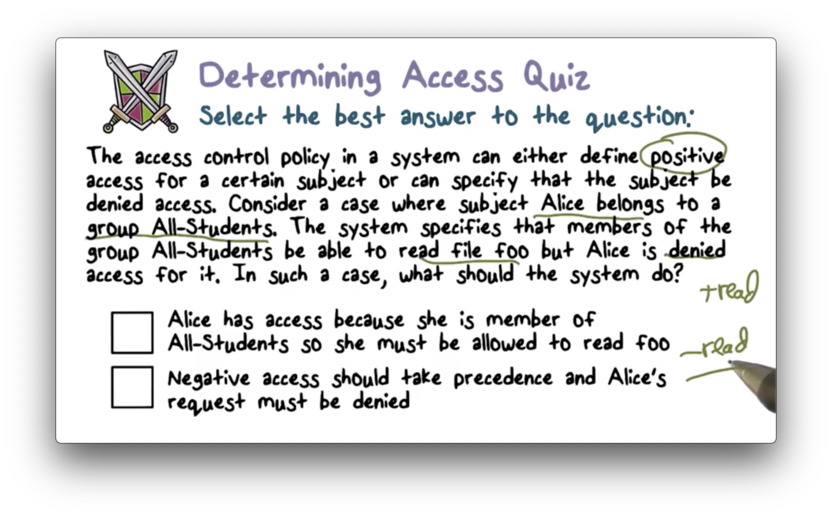

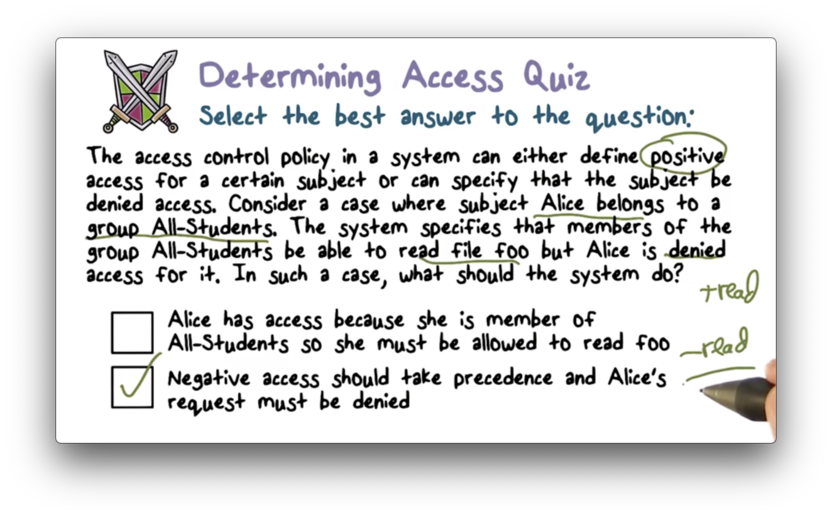

Determining Access Quiz

Determining Access Quiz Solution

Access control conflicts can be securely resolved by denying access.

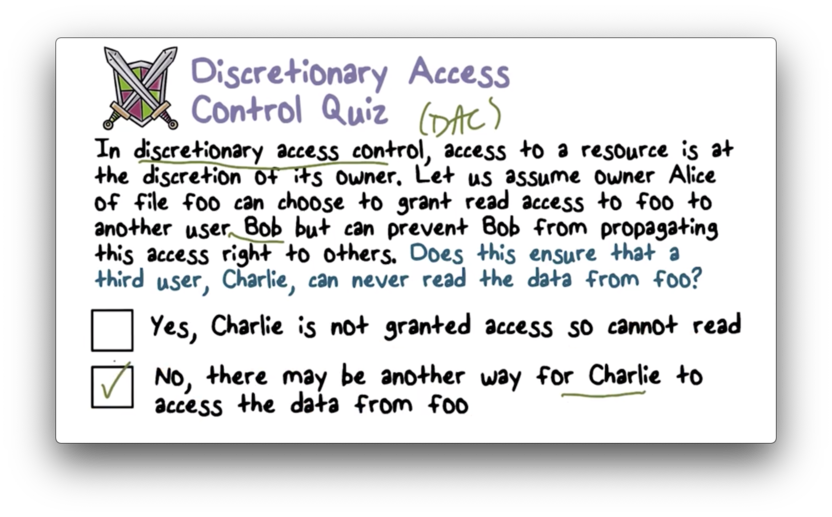

Discretionary Access Control Quiz

Discretionary Access Control Quiz Solution

Bob can write the contents of the file to a new file that he owns, and share that file with Charlie.

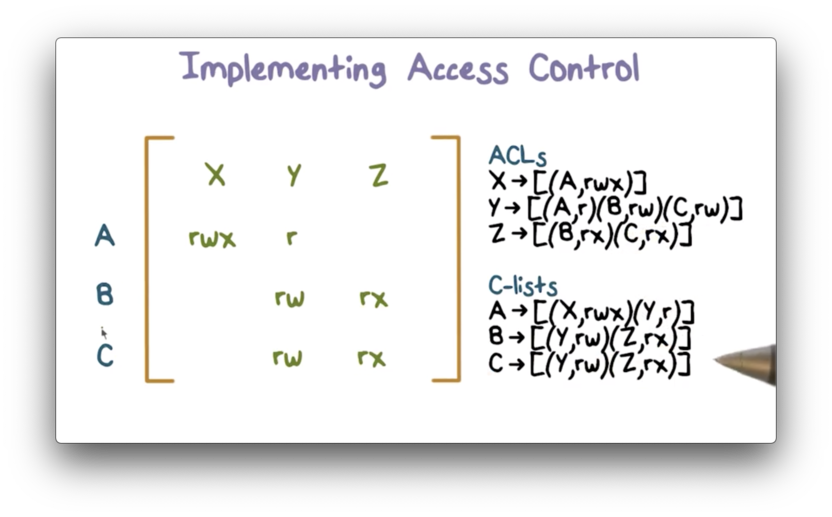

Implementing Access Control

A system will likely have multiple users and many different objects that it needs to protect; therefore, an access control matrix can be very large.

This matrix will also be relatively sparse. With many users in a system, and many objects that any individual user cannot access, the majority of the cells in the matrix will be empty.

How should we represent the access control matrix within our system?

If we focus on each column of the matrix, we can make a list of all of the access rights users have for a given object.

Consider an object O. If user A has read access to O and user B has write access to O, and user C has no access to O, we can represent the accesses permitted on O as

[(A, r), (B,w)]This is called an access control list (ACL). ACLs are associated with each resource, and enumerate the authorized users and types of operations permitted on that resource.

Alternatively, we can focus on each row in the matrix, which corresponds to a particular user.

Consider a user U. If U can read object X, and can write object Y, but cannot access object Z, we can represent the authorized operations that U can perform as

[(X, r), (Y, w)]This type of list is called a capability list (C-list), and identifies which objects a user can access and in what fashion.

Example Access Control Matrix

In this example, we have a system with users A, B, and C, and objects X, Y, and Z.

We can create ACLs by looking "down" the column for each object, and we can create C-lists by looking "across" the row for each user.

ACL Implementation

Since an ACL determines who can access a resource that needs to be protected, ACLs must be stored in the kernel. Otherwise, any untrusted application could change access rules arbitrarily.

Within the kernel, one natural place to store an ACL for a resource is the same place that we store other metadata for that resource.

For example, a file has a bunch of metadata associated with block locations and file size and so forth, so storing the ACL with this metadata seems logical.

When a request for an object occurs, the operating system must traverse the ACL to determine if an access control entry (ACE) is present for the requesting user and, if so, whether the requested action is permitted.

For example, if user A is trying to read file F, the operating system must retrieve the ACL for F, find the ACE for A and check to see whether the "read" operation is present in the list of authorized operations.

C Lists Implementation

A capability is an unforgeable handle for a resource, which a user can present to the system to gain access to the resource. A capability is essentially a token that proves that a user has been given permission to access a resource.

Since capabilities have this unforgeable requirement, they must be stored in the kernel. Unlike ACLs, they are not going to be stored with resources themselves, since they are not scoped to individual objects.

Instead, the kernel must maintain a user catalogue of capabilities that defines what any particular user can access.

In some cases, a C-list can be stored in the objects or resources themselves, as was in the case in the Hydra operating system from Carnegie Mellon, but this is less common.

How can authorizations be shared?

In the case of ACLs, a user who has permission to grant access to a resource can make a system call and authorize that access for another user. The operating system will create a new ACE for the newly authorized user and add it to the ACL for the resource.

For C-lists, sharing requires propagation of capabilities from one user to another.

Possession of a capability means that you can access the resource. There is no system-level access check as is the case with ACLs.

ACL and C Lists Implementation: ACL vs C list

If we are developing a new operating system, should we use ACLs or C-lists? What are the pros and cons of choosing one over the other?

Efficiency

With ACLs, the system needs to traverse the ACL in order to find an ACE corresponding to the user who made the request. There is some processing overhead associated with this traversal.

With capability lists, the mere presentation of a capability is sufficient to access a resource. The system does not have to perform any further checks.

In this manner, C-lists are more efficient than ACLs.

Accountability

If you want to know all of the users that have access to a particular resource, you can do this really easily with an ACL since, by definition, it contains the list of users and authorized actions for a given resource.

To determine the same information using C-lists, the system will need to look in every user catalogue and extract the authorizations for the resource in question.

Because of this, accountability is more transparent with ACLs.

Revocation

Revocation refers to removing access to a given object for a given user after some initial access has been granted.

Alice can easily revoke Bob's access to file foo if ACLs are used. She can simply make a system call, and the system will locate the ACL for foo, find the ACE corresponding to Bob, and remove the appropriate permission.

For C-lists, Alice can't remove permissions from Bob's catalogue at will.

Revocation is easier to perform using ACLs.

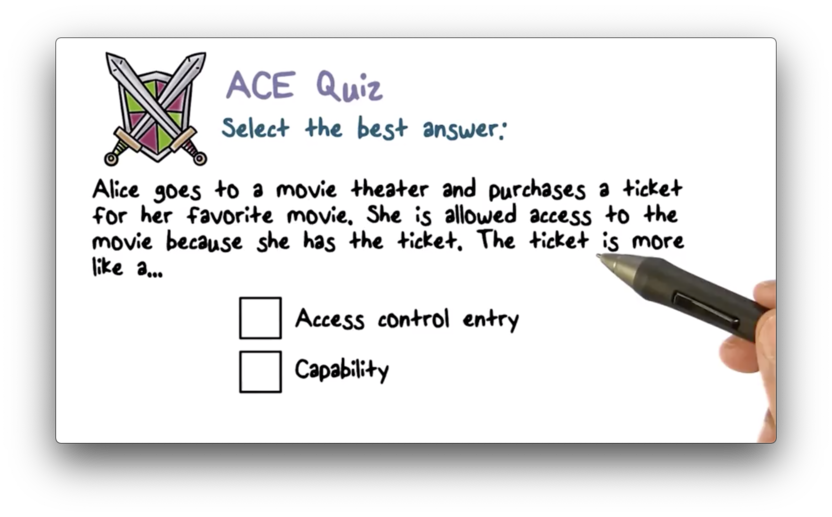

ACE Quiz

ACE Quiz Solution

The presentation of the ticket is sufficient to gain access to the theater. No other access checks are required. This is closest in functionality to a capability.

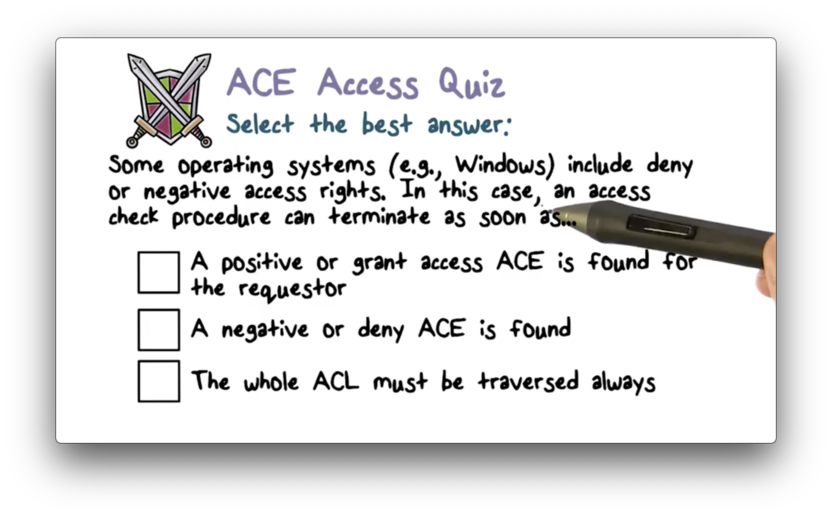

ACE Access Quiz

ACE Access Quiz Solution

Negative access rights supersede positive access rights, so you can't terminate as soon as you find a positive access right. You can terminate as soon as you find a negative access right, though.

NB: The third option can't be true if the second option is true.

Revocation of Rights Quiz

Revocation of Rights Quiz Solution

Access Control Implementation Part 1

In Unix, every resource that needs protection is represented as a file.

All users in Unix systems have a unique user id (UID). Users can belong to groups, which each have their own group id (GID). There is a special world group which contains every user in the system.

Since resources are files, they can be read, written or executed.

In the access control matrix, each row corresponds to each entity in the system: each UID, each GID, and the special world group. Each column corresponds to each file in the system. Each entry will be a subset of read/write/execute.

The original ACL implementation in Unix systems had a compact, fixed size representation representing the read, write, and execute permissions for the user, the group, and the world.

These three ACEs were represented as a nine bit mask such as 111110100. You may have seen this mask in a slightly different format: rwxrw-r-- if you have ever run the ls -l command on your Unix machine.

This ACL structure is limited in its flexibility since it provides only three levels of authorization granularity.

Modern operating systems - Linux, BSD, MacOS - provide full ACL support in order to make access control as flexible as necessary.

Access Control Implementation SetUID

Consider the following scenario.

Alice owns an executable file that launches a computer game. Alice also owns a text file that contains the scores of the users playing the game.

Alice wants to allow any user to execute the game file, but wants to restrict write access to the score file unless the game is being played.

We can solve this problem with the setuid bit. If this bit is set on an executable file, a process executing this file takes on the effective user id of the owner of the file - not the current user - for the duration of the execution.

In other words, when Bob runs Alice's game, the process that is created by Bob has Alice's UID associated with it. This means that Bob can access the score file - which Alice owns - while he plays the game so he can record his scores.

Since the effective UID is set on a per-process basis, this temporary privilege will go away once Bob closes the game.

Access Control Implementation Part 2

A file can be opened with the open system call. If the file doesn't exist, this call will create the file and then open it.

The open system call takes two arguments: the name of the file and the mode in which you want to access the file. The mode can be read or write, for example.

Once we open a file, the operating system returns a file descriptor, which is a small integer. In order to read, write or close a file, we need to pass this descriptor back to the operating system.

If you want to read a file, you can pass the file descriptor to the read system call. The call to read takes two arguments: the buffer into which you wish to read the data, and the number of bytes you wish to read.

Similarly, there is a write system call, which writes a supplied number of bytes from a supplied buffer back into the file referenced by the file descriptor.

When you are done with the file, you can close it with the close system call, which also takes the file descriptor as an argument.

Read more about open, read, write, and close.

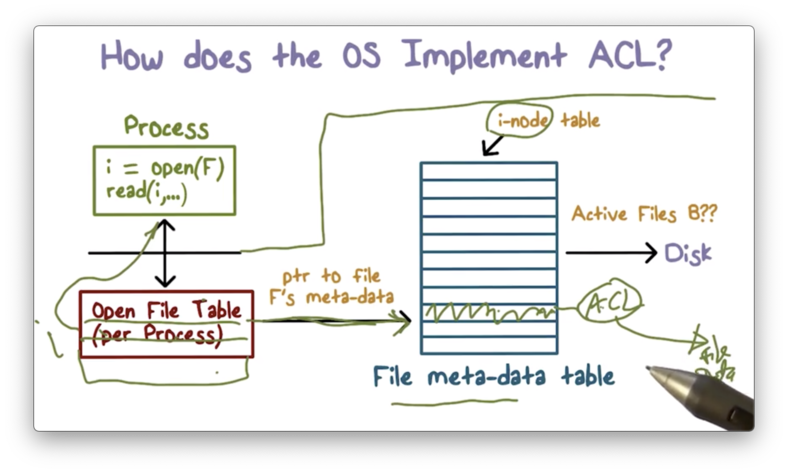

How does the OS Implement ACL?

What happens when you open a file?

When we execute the open system call, the very first thing that happens is that we switch into kernel mode and start executing from within the operating system.

Every file has metadata associated with it. This metadata can contain disk block locations, file size, file name, and the ACL.

The data structure that contains this metadata is referred to as an inode on Unix systems, and the operating system maintains a table of inodes for all of the files in the system that are actively being accessed.

When we attempt to open a file, the operating system will check the inode table to see if there is an entry for the given process. If not, the operating system will create an entry for that file.

Once the inode for the file is located, access control is performed. The system will locate the ACL and will decide whether to grant access or not based on the bits present in the ACL and the mode in which the user is requesting to open the file.

If the system determines that access should not be granted, the requesting process is not given with a file descriptor.

If the system determines that access should be granted, it will create an entry in another table, the per-process file descriptor table. This table holds pointers to the inode table and contains all of the files currently being accessed by the given process.

The file descriptor returned from this call is nothing more than an index into that table.

What is important to understand here is that after the file descriptor is returned, there are no subsequent access checks. If your permissions to read a file are removed after you have opened a file for reading, you can continue reading using that file descriptor.

Of course, if a process opens a file for reading and then tries to write to the file, the system will prevent it.

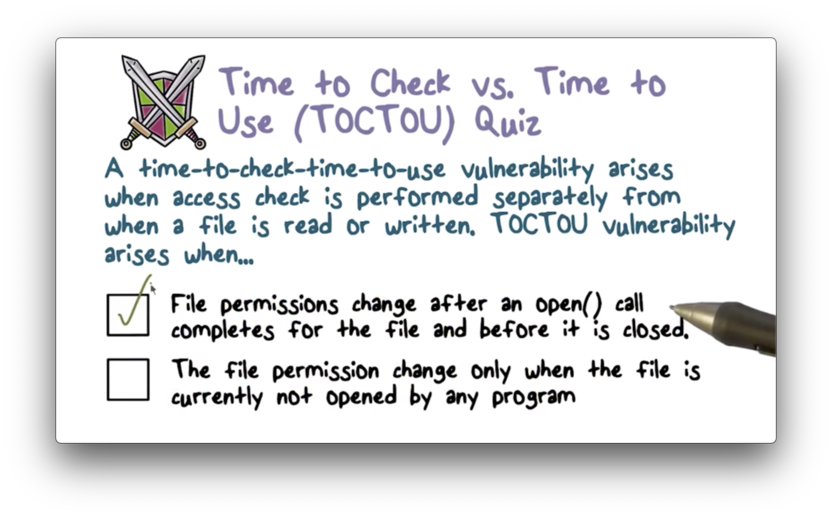

Time to Check vs Time to Use Quiz

Time to Check vs Time to Use Quiz Solution

As long as you had the permissions when you called open, you can access the file using the file descriptor.

Unix File Sharing Quiz

Unix File Sharing Quiz Solution

You would need to somehow add the descriptor to the per-process descriptor table for the process with which you wish to share the descriptor. Since the OS owns this table, mutating it is impossible.

SetUID Bit Quiz

SetUID Bit Quiz Solution

The effective UID of a process executing a file with the setuid bit set is the owner of the file, not the user who created the process.

Role Based Access Control

Some systems use role-based access control (RBAC). In RBAC, the rights to access certain resources are associated with roles instead of users.

Once a user authenticates with the system, they can take on one or more roles that allow them to interact with the system in certain ways.

A role is often closely linked to job function. For example, people in payroll might assume a role that allows them to access salary data, while engineers might have a role that allows them to deploy code.

A user can have more than one role. The employees described above might take on a general employee role which allows them to connect to a local intranet or access a company directory.

Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) supports RBAC.

RBAC Benefits

Since the policy defines which roles have access to which resources, the policy doesn't need to change when any one user leaves the organization.

In addition, a new employee can easily be set up. Instead of having to assign them individual privileges one by one, a system administrator can assign them to one or more roles and instantly grant the appropriate amount of access.

In these regards, RBAC makes policy administration simpler.

Least Privilege

Remember, least privilege is the idea that a user should always execute with the smallest number of privileges or access rights needed to complete a task.

The point of least privilege is really damage containment. If something goes wrong, a user can't damage resources that they had no business accessing in the first place.

In RBAC, a user can start in one role and access a subset of the files that are only available to that role. At a later point, the user can switch roles and access a different set of files associated with the new role.

Without roles, a user just has static access to the complete universe of things they would ever need to access. Roles allow for much tighter access control scoped by functionality.

RBAC Benefits Quiz

RBAC Benefits Quiz Solution

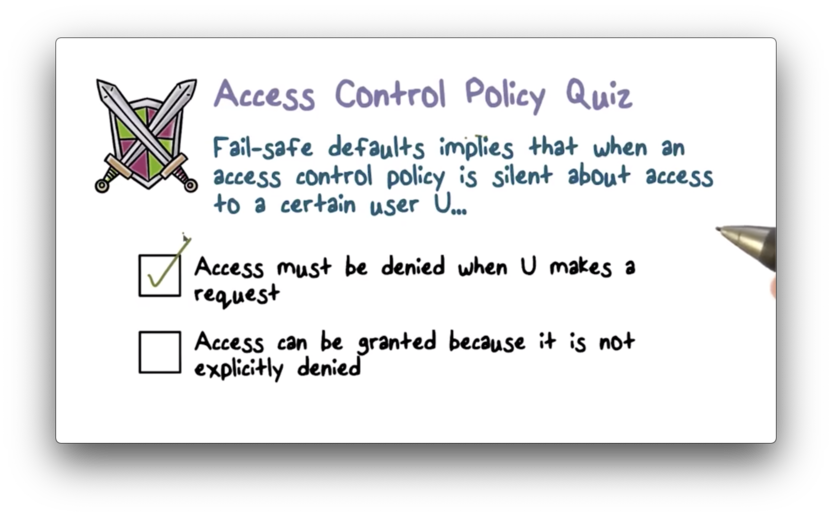

Access Control Policy Quiz

Access Control Policy Quiz Solution

From a security standpoint, denying access is a fail-safe default. It never fails to keep your system secure.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy