Computer Networks

Software Defined Networking (Part 1)

17 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Software Defined Networking (Part 1)

What led us to SDN?

Software Defined Networking (SDN) arose as part of the process to make computer networks more programmable. Computer networks are very complex and especially difficult to manage for two main reasons:

Diversity of equipment on the network

- Proprietary technologies for the equipment

- Diversity of equipment

Computer networks have a wide range of equipment - from routers and switches to middleboxes such as firewalls, network address translators, server load balancers, and intrusion detection systems (IDSs). The network has to handle different software adhering to different protocols for each of these equipment. Even with a network management tool offering a central point of access, they still have to operate at a level of individual protocols, mechanisms and configuration interfaces, making network management very complex.

Proprietary Technologies

Equipment like routers and switches tend to run software which is closed and proprietary. This means that configuration interfaces vary between vendors. In fact, these interfaces could also differ between different products offered by the same vendor! This makes it harder for the network to manage all these devices centrally.

These characteristics of computer networks made them highly complex, slow to innovate, and drove up the costs of running a network.

SDN offers new ways to redesign networks to make them more manageable! It employs a simple idea - separation of tasks. We've seen that our code becomes more modular and easy to manage when we divide them into smaller functions with focused tasks. Similarly, SDN divides the network into two planes - control plane and data plane. It uses this separation to simplify management and speed up innovation!

A Brief History of SDN: The Milestones

In this section, we are providing an overview of the history of SDN, as a summary based on the paper "The Road to SDN: An Intellectual History of Programmable Networks" http://www.sigcomm.org/sites/default/files/ccr/papers/2014/April/0000000-0000012.pdf

The history of SDN can be divided into three phases:

- Active networks

- Control and data plane separation

- OpenFlow API and network operating systems

Lets take a look at each phase.

Active networks

This phase took place from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s. During this time, the internet takeoff resulted in an increase in the applications and appeal of the internet. Researchers were keen on testing new ideas to improve network services. However, this required standardization of new protocols by the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force), which was a slow and frustrating process.

This tediousness led to the growth of active networks, which aimed at opening up network control. Active networking envisioned a programming interface (a network API) that exposed resources/network nodes and supported customization of functionalities for subsets of packets passing through the network nodes. This was the opposite of the popular belief in the internet community - the simplicity of the network core was important to the internet success!

In the early 1990s, the networking approach was primarily via IP or ATM (Asynchronous Transfer Mode). Active networking became one of the first ‘clean slate' approaches to network architecture.

There were two types of programming models in active networking. These models differ based on where the code to execute at the nodes was carried.

- Capsule model – carried in-band in data packets

- Programmable router/switch model – established by out-of-band mechanisms.

Although the capsule model was most closely related to active networking, both models have some effect on the current state of SDNs. By carrying the code in data packets, capsules brought a new data-plane functionality across networks. They also used caching to make code distribution more efficient. Programmable routers made decision making a job for the network operator.

Technology push

The pushes that encouraged active networking were:

- Reduction in computation cost. This enabled us to put more processing into the network.

- Advancement in programming languages. For languages like Java, the options of platform portability, code execution safety, and VM (virtual machine) technology to protect the active node in case of misbehaving programs.

- Advances in rapid code compilation and formal methods.

- Funding from agencies such as DARPA (U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) for a collection promoted interoperability among projects. This was especially beneficial because there were no short-term use cases to use to alleviate the skepticism people had about the use of active networking.

Use pull

The use pulls for active networking were:

- Network service provider frustration concerning the long timeline to develop and deploy new network services.

- Third party interests to add value by implementing control at a more individualistic nature. This meant dynamically meeting the needs of specific applications or network conditions.

- Researchers interest in having a network that would support large-scale experimentation.

- Unified control over middleboxes. We discussed the disadvantage of having diverse programming models which varied not only based on the type of middlebox (for example, firewalls, proxies, etc) but based on the vendor. Active networking envisioned unified control that could replace individually managing these boxes. This actually foreshadows the trends we see now in network functions virtualization – where we also attempt to provide a central unifying framework for networks with complex middlebox functions. It is interesting to note that the use pulls for active networks in the mid-1990s are similar to those for SDN now!

In addition to these use cases, active networks made three major contributions related to SDN:

-

Programmable functions in the network to lower the barrier to innovation.

Active networks were one of the first to introduce the idea of using programmable networks to overcome the slow speed of innovation in computer networking. While many early visions for SDN concentrated on increasing programmability of the control-plane, active networks focused on the programmability of the data-plane. This has continued to develop independently. Recently, this data-plane programmability has been gaining more traction due to the emerging NFV initiatives. In addition, the concept of isolating experimental traffic from normal traffic had emerged from active networking and is heavily used in OpenFlow and other SDN technologies.

-

Network virtualization, and the ability to demultiplex to software programs based on packet headers.

Active networking produced a framework that described a platform that would support experimentation with different programming models. This was the need that led to network visualization.

-

The vision of a unified architecture for middlebox orchestration.

The last use-pull for SDN, i.e., unified control over middleboxes was never fully realized in the era of active networking. While it did not directly influence network function virtualization (NFV), some lessons from its research is useful while trying to implement unified architecture now!

One of the biggest downfalls for active networking was that it was too ambitious! Since it required end users to write Java code, it was too far removed from the reality at that time, and hence was not trusted to be safe. Since active networking was more involved in redesigning the architecture of networks, not as much emphasis was given to performance and security – which users were more concerned about. However, it is worthwhile to note that some efforts did aim to build high-performance active routers, and there were a few notable projects that did address the security of networks. Since there were no specific short-term problems that active networks solved, it was harder for them to see widespread deployment. The next efforts had a more focused scope and distinguished between control and data planes. This difference made it easier to focus on innovation in a specific plane and inflict widespread change.

Control and data plane separation

This phase lasted from around 2001 to 2007. During this time, there was a steady increase in traffic volumes and thus, network reliability, predictability and performance became more important. Network operators were looking for better network-management functions such as control over paths to deliver traffic (traffic engineering). Researchers started exploring short-term approaches that were deployable using existing protocols. They identified the challenge in network management lay in the way existing routers and switches tightly integrated the control and data planes. Once this was identified, efforts to separate the two began.

Technology push

The technology pushes that encouraged control and data plane separation were:

- Higher link speeds in backbone networks led vendors to implement packet forwarding directly in the hardware, thus separating it from the control-plane software.

- Internet Service Providers (ISPs) found it hard to meet the increasing demands for greater reliability and new services (such as virtual private networks), and struggled to manage the increased size and scope of their networks.

- Servers had substantially more memory and processing resources than those deployed one-two years prior. This meant that a single server could store all routing states and compute all routing decisions for a large ISP network. This also enabled simple backup replication strategies – thus, ensuring controller reliability.

- Open source routing software lowered the barrier to creating prototype implementations of centralized routing controllers.

These pushes inspired two main innovations:

- Open interface between control and data planes

- Logically centralized control of the network

This phase was different from active networking in several ways:

- It focused on spurring innovation by and for network administrators rather than end users and researchers.

- It emphasized programmability in the control domain rather than the data domain.

- It worked towards network-wide visibility and control rather than device-level configurations.

Use pulls

Some use pulls for the separation of control and data planes were:

- Selecting between network paths based on the current traffic load

- Minimizing disruptions during planned routing changes

- Redirecting/dropping suspected attack traffic

- Allowing customer networks more control over traffic flow

- Offering value-added services for virtual private network customers

Most work during this phase tried to manage routing within a single ISP, but there were some proposals about ways to enable flexible route control across many administrative domains.

The attempt to separate the control and data planes resulted in a couple of concepts which were used in further SDN design:

- Logically centralized control using an open interface to the data plane.

- Distributed state management.

Initially, many people thought separating the control and data planes was a bad idea, since there was no clear idea as to how these networks would operate if a controller failed. There was also some skepticism about moving away from a simple network where all have a common view of the network state to one where the router only had a local view of the outcome of route-selection. However, this concept of separation of planes helped researchers think clearly about distributed state management. Several projects exploring clean-slate architecture commenced and laid the foundation for OpenFlow API.

OpenFlow API and network operating systems

This phase took place from around 2007 to 2010. OpenFlow was born out of the interest in the idea of network experimentation at a scale (by researchers and funding agencies). It was able to balance the vision of fully programmable networks and the practicality of ensuring real world deployment. OpenFlow built on the existing hardware and enabled more functions than earlier route controllers. Although this dependency on hardware limited its flexibility, it enabled immediate deployment.

The basic working of an OpenFlow switch is as follows. Each switch contains a table of packet-handling rules. Each rule has a pattern, list of actions, set of counters and a priority. When an OpenFlow switch receives a packet, it determines the highest priority matching rule, performs the action associated with it and increments the counter.

Technology push

OpenFlow was adopted in the industry, unlike its predecessors. This could be due to:

- Before OpenFlow, switch chipset vendors had already started to allow programmers to control some forwarding behaviors.

- This allowed more companies to build switches without having to design and fabricate their own data plane.

- Early OpenFlow versions built on technology that the switches already supported. This meant that enabling OpenFlow initially was as simple as performing a firmware upgrade!

Use pulls

- OpenFlow came up to meet the need of conducting large scale experimentation on network architectures. In the late 2000s, OpenFlow testbeds were deployed across many college campuses to show its capability on single-campus networks and wide area backbone networks over multiple campuses.

- OpenFlow was useful in data-center networks – there was a need to manage network traffic at large scales.

- Companies started investing more in programmers to write control programs, and less in proprietary switches that could not support new features easily. This allowed many smaller players to become competitive in the market by supporting capabilities like OpenFlow.

Some key effects that OpenFlow had were:

- Generalizing network devices and functions.

- The vision of a network operating system.

- Distributed state management techniques.

Why Separate the Data Plane from the Control Plane?

Why separate the control from the data plane?

We know that SDN differentiates from traditional approaches by separating the control and data planes.

The control plane contains the logic that controls the forwarding behavior of routers such as routing protocols and network middlebox configurations. The data plane performs the actual forwarding as dictated by the control plane. For example, IP forwarding and Layer 2 switching are functions of the data plane.

The reasons we separate the two are:

-

Independent evolution and development

In the traditional approach, routers are responsible for both routing and forwarding functionalities. This meant that a change to either of the functions would require an upgrade of hardware. In this new approach, routers only focus on forwarding. Thus, innovation in this design can proceed independently of other routing considerations. Similarly, improvement in routing algorithms can take place without affecting any of the existing routers. By limiting the interplay between these two functions, we can develop them more easily.

-

Control from high-level software program

In SDN, we use software to compute the forwarding tables. Thus, we can easily use higher-order programs to control the routers' behavior. The decoupling of functions makes debugging and checking the behavior of the network easier.

Separation of the control and data planes supports the independent evolution and development of both. Thus, the software aspect of the network can evolve independent of the hardware aspect. Since both control and forwarding behavior are separate, this enables us to use higher-level software programs for control. This makes it easier to debug and check the network's behavior.

In addition, this separation leads to opportunities in different areas.

- Data centers. Consider large data centers with thousands of servers and VMs. Management of such large network is not easy. SDN helps to make network management easier.

- Routing. The interdomain routing protocol used today, BGP, constrains routes. There are limited controls over inbound and outbound traffic. There is a set procedure that needs to be followed for route selection. Additionally, it is hard to make routing decisions using multiple criteria. With SDN, it is easier to update the router's state, and SDN can provide more control over path selection.

- Enterprise networks. SDN can improve the security applications for enterprise networks. For example, using SDN it is easier to protect a network from volumetric attacks such as DDoS, if we drop the attack traffic at strategic locations of the network.

- Research networks. SDN allows research networks to coexist with production networks.

Control Plane and Data Plane Separation

Two important functions of the network layer are:

Forwarding

Forwarding is one of the most common, yet important functions of the network layer. When a router receives a packet at its input link, it must determine which output link that packet should be sent through. This process is called forwarding. It could also entail blocking a packet from exiting the router, if it is suspected to have been sent by a malicious router. It could also duplicate the packet and send it along multiple output links. Since forwarding is a local function for routers, it usually takes place in nanoseconds and is implemented in the hardware itself. Forwarding is a function of the data plane.

So, a router looks at the header of an incoming packet and consults the forwarding table, to determine the outgoing link to send the packet to.

Routing

Routing involves determining the path from the sender to the receiver across the network. Routers rely on routing algorithms for this purpose. It is an end-to-end process for networks. It usually takes place in seconds and is implemented in the software. Routing is a function of the control plane.

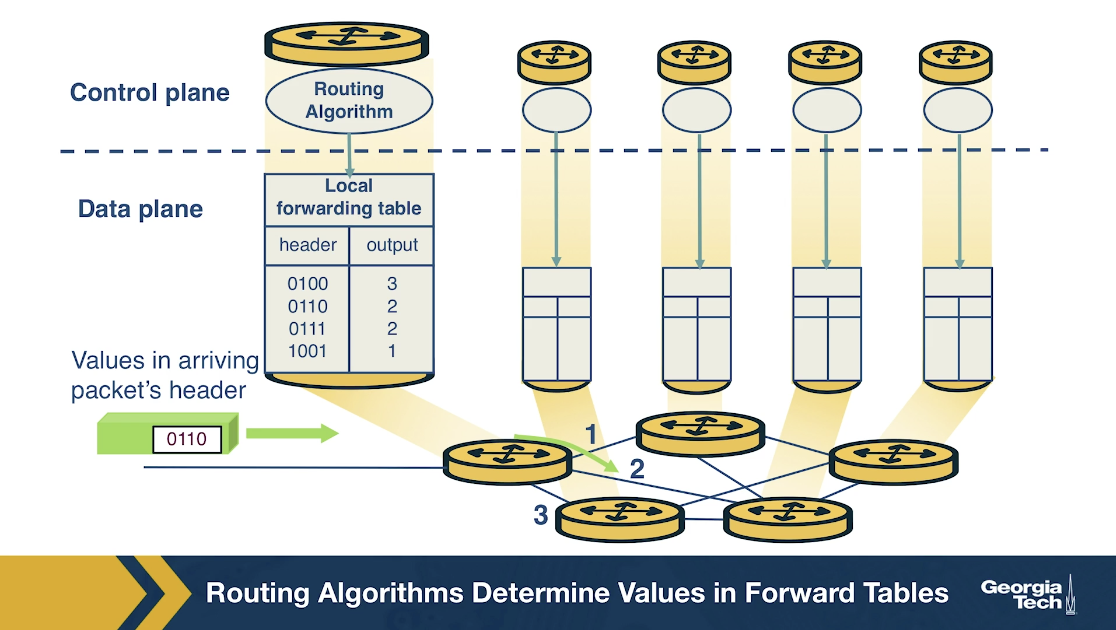

In the traditional approach, the routing algorithms (control plane) and forwarding function (data plane) are closely coupled. The router runs and participates in the routing algorithms. From there it is able to construct the forwarding table which consults it for the forwarding function.

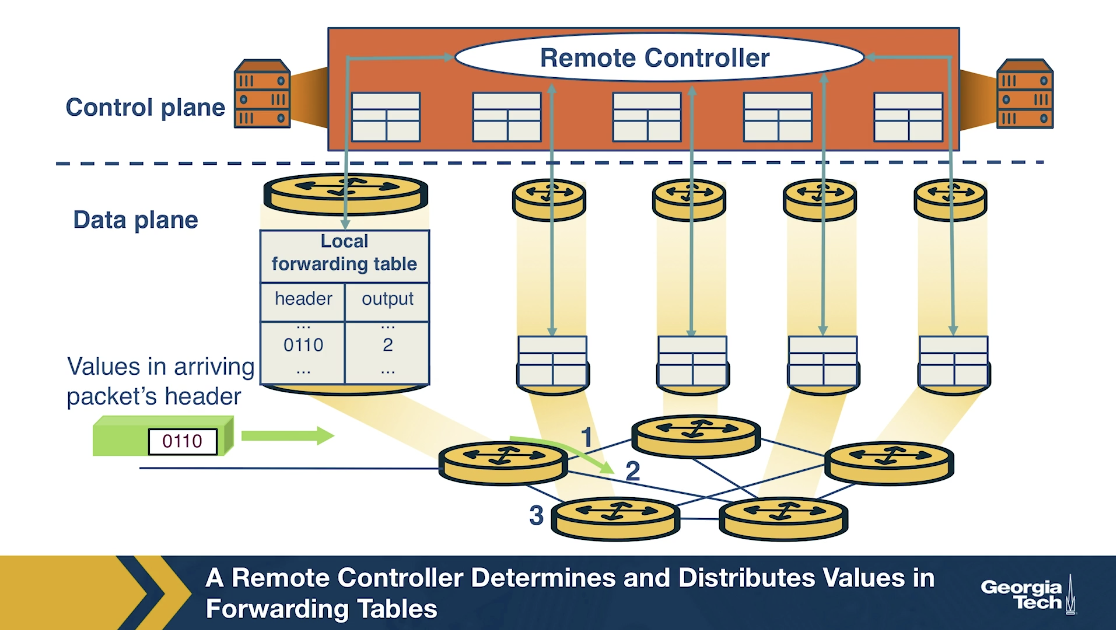

In the SDN approach, on the other hand, there is a remote controller that computes and distributes the forwarding tables to be used by every router. This controller is physically separate from the router. It could be located in some remote data center, managed by the ISP or some other third party.

We have a separation of the functionalities. The routers are solely responsible for forwarding, and the remote controllers are solely responsible for computing and distributing the forwarding tables. The controller is implemented in software, and therefore we say the network is software-defined.

These software implementations are also increasingly open and publicly available, which speeds up innovation in the field.

The SDN Architecture

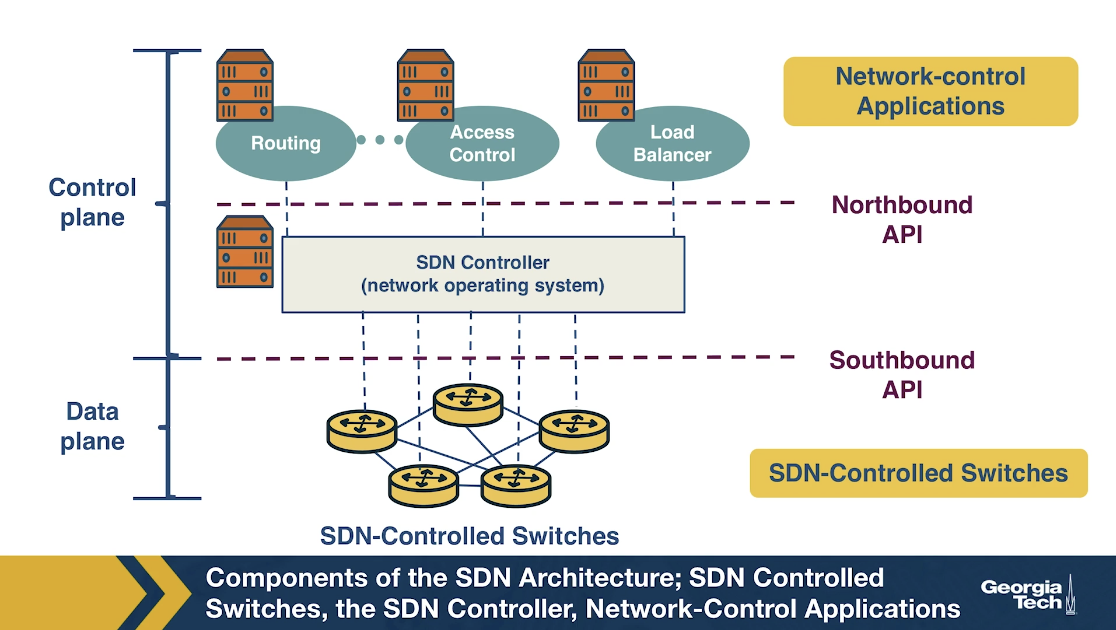

In the figure below we see the main components of an SDN network:

SDN-controlled network elements

The SDN-controlled network elements, sometimes called the infrastructure layer, is responsible for the forwarding of traffic in a network based on the rules computed by the SDN control plane.

SDN controller

The SDN controller is a logically centralized entity that acts as an interface between the network elements and the network-control applications.

Network-control applications

The network-control applications are programs that manage the underlying network by collecting information about the network elements with the help of SDN controller.

Let us now take a look at the four defining features in an SDN architecture:

- Flow-based forwarding: The rules for forwarding packets in the SDN-controlled switches can be computed based on any number of header field values in various layers such as the transport-layer, network-layer and link-layer. This differs from the traditional approach where only the destination IP address determines the forwarding of a packet. For example, OpenFlow allows up to 11 header field values to be considered.

- Separation of data plane and control plane: The SDN-controlled switches operate on the data plane and they only execute the rules in the flow tables. Those rules are computed, installed, and managed by software that runs on separate servers.

- Network control functions: The SDN control plane, (running on multiple servers for increased performance and availability) consists of two components: the controller and the network applications. The controller maintains up-to-date network state information about the network devices and elements (for example, hosts, switches, links) and provides it to the network-control applications. This information, in turn, is used by the applications to monitor and control the network devices.

- A programmable network: The network-control applications act as the “brain” of SDN control plane by managing the network. Example applications can include network management, traffic engineering, security, automation, analytics, etc. For example, we can have an application that determines the end-to-end path between sources and destinations in the network using Dijkstra's algorithm.

The SDN Controller Architecture

The SDN controller is a part of the SDN control plane and acts as an interface between the network elements and the network-control applications.

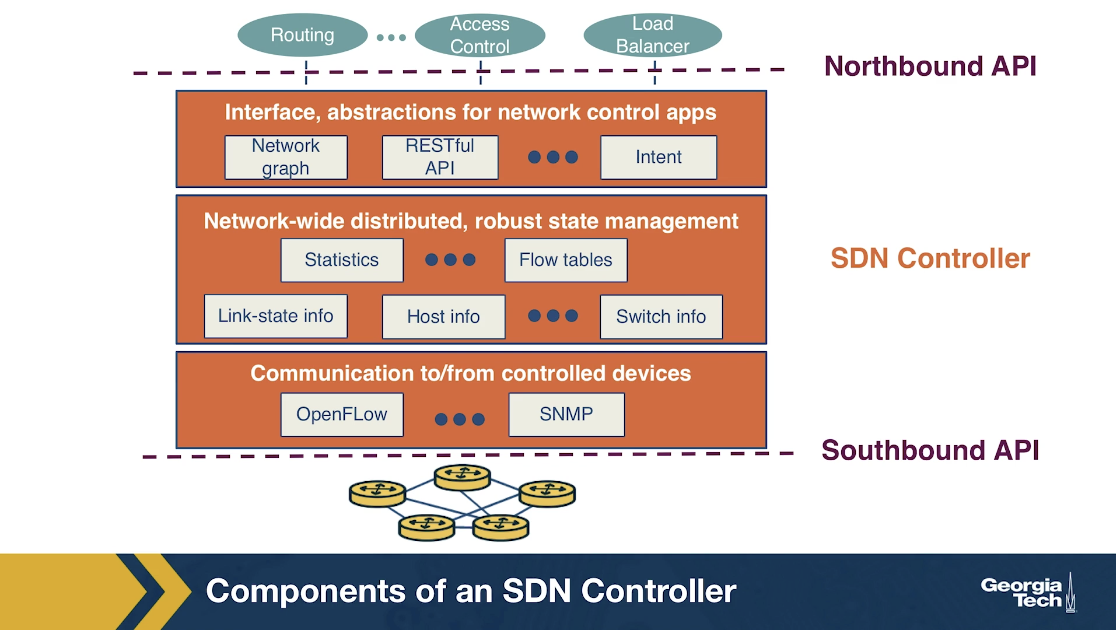

An SDN controller can be broadly split into three layers:

- Communication layer: communicating between the controller and the network elements

- Network-wide state-management layer: stores information of network-state

- Interface to the network-control application layer: communicating between controller and applications

Let's look at each layer in detail starting from the bottom:

Communication Layer

This layer consists of a protocol through which the SDN controller and the network controlled elements communicate. Using this protocol, the devices send locally observed events to the SDN controller providing the controller with a current view of the network state. For example, these events can be a new device joining the network, heartbeat indicating the device is up, etc. The communication between SDN controller and the controlled devices is known as the “southbound” interface. OpenFlow is an example of this protocol, which is broadly used by SDN controllers today.

Network-wide state-management layer

This layer is about the network-state that is maintained by the controller. The network-state includes any information about the state of the hosts, links, switches and other controlled elements in the network. It also includes copies of the flow tables of the switches. Network-state information is needed by the SDN control plane to configure the flow tables.

Interface to the network-control application layer

This layer is also known as the controller's “northbound” interface using which the SDN controller interacts with network-control applications. Network-control applications can read/write network state and flow tables in controller's state-management layer. The SDN controller can notify applications of changes in the network state, based on the event notifications sent by the SDN-controlled devices. The applications can then take appropriate actions based on the event. A REST interface is an example of a northbound API.

The SDN controller, although viewed as a monolithic service by external devices and applications, is implemented by distributed servers to achieve fault tolerance, high availability and efficiency. Despite the issues of synchronization across servers, many modern controllers such as OpenDayLight and ONOS have solved it and prefer distributed controllers to provide highly scalable services.

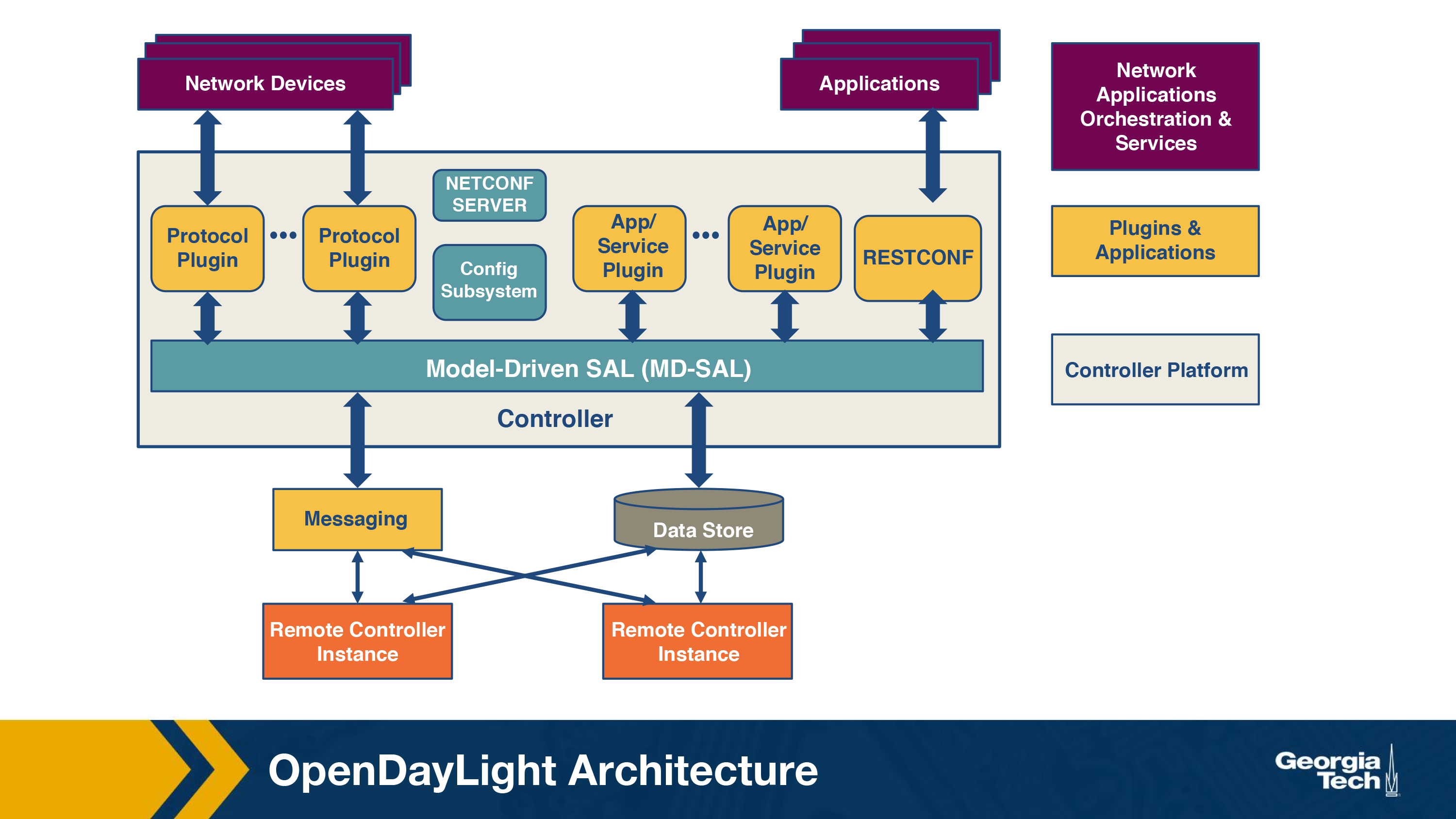

OpenDayLight Architecture Overview

In the previous topics we looked at the SDN Controller architecture. We talked about the Southbound and Northbound interfaces, and how the SDN controller uses them to interact with other components.

In this topic, we will first take a look at the OpenDaylight controller architecture:

- Southbound interface: This is used by the controller to communicate with network devices. The interface also allows support for various third-party vendor specific protocols like openflow, netflow, netconf etc. We can also write our own plugin in the Southbound interface.

- Northbound interface: As the name suggests, it's an “upward” bound interface so that SDN applications can talk to the controller platform underneath (see figure below). For eg an application to check connectivity of the network, the ping packets are sent to the Northbound interface to the controller, the controller parses information and will pass on the packets to the device interface via the Southbound API.

-

Model Driven Service Abstraction Layer (or MD-SAL): It is the abstraction layer provided by OpenStack for developers to add new features to the controller. Using karaf they can write services or protocol drivers to integrate them together. MDSAL has 2 components:

-

A shared datastore that has 2 tree based structures:

- Config Datastore: This manages the representation of the network. It also does the sanity checking for any new services. For eg if you try to deploy a service to configure an interface, you use a chain of commands. This component manages how these changes are pushed.

- Operation Datastore: This has the true representation of the network state based on data from the managed network elements. Once the final committed changes are reflected to the network devices, we save the data in this store.

- A message bus that provides a way for various services and protocol drivers to notify and communicate with each other.

-

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy