Computer Networks

Internet Surveillance and Censorship

19 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Internet Surveillance and Censorship

DNS Censorship: What is it?

We will explore different censorship types and techniques. In this topic we will start with DNS based censorship.

What is DNS censorship?

DNS censorship is a large scale network traffic filtering strategy opted by a network to enforce control and censorship over Internet infrastructure to suppress material which they deem as objectionable. An example of large scale DNS censorship is that implemented by networks located in China, which use a Firewall, popularly known as the Great Firewall of China (GFW). This Firewall looks like is an opaque system that uses various techniques to censor China's internet traffic and block access to various foreign websites.

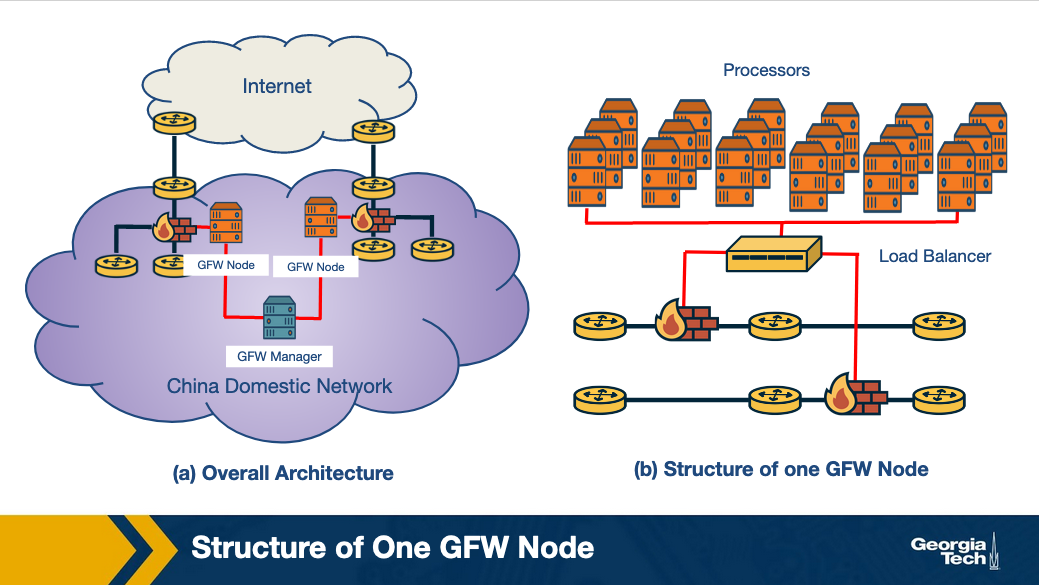

The GFW (shown in the figure above) works on injecting fake DNS record responses so that access to a domain name is blocked. Since the GFW is an opaque system, several different studies have been performed to deduce the actual nature of the system and its functionality.

Researchers have tried to reverse engineer the GFW and to understand how it works. Based on research (Towards a Comprehensive Picture of the Great Firewall's DNS Censorship https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/foci14/foci14-anonymous.pdf (Links to an external site.)), researchers have started to identify some of the properties:

- Locality of GFW nodes: There are two differing notions on whether the GFW nodes are present only at the edge ISPs or whether they are also present in non-bordering Chinese ASes. The majority view is that censorship nodes are present at the edge.

- Centralized management: Since the blocklists obtained from two distinct GFW locations are the same, there is a high possibility of a central management (GFW Manager) entity that orchestrates blocklists.

- Load balancing: GFW load balances between processes based on source and destination IP address. The processes are clustered together to collectively send injected DNS responses.

Organizations that track the GFW

There are multiple organizations that monitor Chinese censorship for censored domains on a continuous basis, some of which are listed below:

- greatfire.org (since 2011)

- hikinggfw.org (since 2012)

Example DNS Censorship Techniques

In the previous topic we started talking about DNS censorship and we saw one example based on the Great Firewall of China (GFW). Researchers have identified (using active probing techniques and measurements) that one of the main first censorship techniques implemented by GFW was based on DNS injection. Let's see how that works.

How does DNS injection work?

DNS injection is one of the most common censorship technique employed by the GFW. The GFW uses a ruleset to determine when to inject DNS replies to censor network traffic. To start with, it is important to identify and isolate the networks that use DNS injection for censorship. The authors of the paper titled “Towards a Comprehensive Picture of the Great Firewall's DNS Censorship” use probing techniques and vantage points to search for injected paths and then evaluate the injection.

When tested against probes for restricted and benign domains, the accuracy of DNS open resolvers to accurately pollute the response is recorded over 99.9%. The steps involved in DNS injection are:

- DNS probe is sent to the open DNS resolvers

- The probe is checked against the blocklist of domains and keywords

- For domain level blocking, a fake DNS A record response is sent back. There are two levels of blocking domains: the first one is by directly blocking the domain, and the second one is by blocking it based on keywords present in the domain

What are the different DNS censorship techniques?

In this section, we will provide an overview of different DNS censorship techniques and look at their strengths and weaknesses. Some of the DNS censorship techniques are more elementary, and some are more elaborate in functioning and implementation. Usually, a censorship system implements these techniques in combination to effect censorship on a network.

Technique 1: Packet Dropping

As the name suggests, in packet dropping, all network traffic going to a set of specific IP addresses is discarded. The censor identifies undesirable traffic and chooses to not properly forward any packets it sees associated with the traversing undesirable traffic instead of following a normal routing protocol.

Strengths

- Easy to implement

- Low cost

Weaknesses

- Maintenance of blocklist - It is challenging to stay up to date with the list of IP addresses to block

- Overblocking - If two websites share the same IP address and the intention is to only block one of them, there's a risk of blocking both

Technique 2: DNS Poisoning

When a DNS receives a query for resolving hostname to IP address- if there is no answer returned or an incorrect answer is sent to redirect or mislead the user request, this scenario is called DNS Poisoning.

Strength

- No overblocking: Since there is an extra layer of hostname translation, access to specific hostnames can be blocked versus blanket IP address blocking.

Technique 3: Content Inspection

3A. Proxy-based content inspection: This censorship technique is more sophisticated, in that it allows for all network traffic to pass through a proxy where the traffic is examined for content, and the proxy rejects requests that serve objectionable content.

Strengths

- Precise censorship: A very precise level of censorship can be achieved, down to the level of single web pages or even objects within the web page

- Flexible: Works well with hybrid security systems e.g. with a combination of other censorship techniques like packet dropping and DNS poisoning

Weakness

- Not scalable: They are expensive to implement on a large scale network as the processing overhead is large (through a proxy)

3B. Intrusion detection system (IDS) based content inspection: An alternative approach is to use parts of an IDS to inspect network traffic. An IDS is easier and more cost effective to implement than a proxy based system as it is more responsive than reactive in nature, in that it informs the firewall rules for future censorship.

Technique 4: Blocking with Resets

The GFW employs this technique where it sends a TCP reset (RST) to block individual connections that contain requests with objectionable content. We can see this by packet capturing of requests that are normal and requests that contain potentially flaggable keywords. Let's look at one such example of packet capture.

Request 1: Requesting a benign web page

Here, we see a packet trace of a web page which is benign:

cam(53382) → china(http) [SYN]

china(http) → cam(53382) [SYN, ACK]

cam(53382) → china(http) [ACK]

cam(53382) → china(http) GET / HTTP/1.0

china(http) → cam(53382) HTTP/1.1 200 OK (text/html) etc. . . china(http) → cam(53382) . . . more of the web page

cam(53382) → china(http) [ACK]

. . . and so on until the page request is complete

Here, the request is from a client in Cambridge (cam53382) to a website based in China (china(http)) which is served successfully

Request 2: Requesting with a potentially flaggable text within the HTTP GET request

Here, we have a packet trace which contains flagged text:

cam(54190) → china(http) [SYN]

china(http) → cam(54190) [SYN, ACK] TTL=39

cam(54190) → china(http) [ACK]

cam(54190) → china(http) GET /?falun HTTP/1.0

china(http) → cam(54190) [RST] TTL=47, seq=1, ack=1

china(http) → cam(54190) [RST] TTL=47, seq=1461, ack=1

china(http) → cam(54190) [RST] TTL=47, seq=4381, ack=1

china(http) → cam(54190) HTTP/1.1 200 OK (text/html) etc. . . cam(54190) → china(http) [RST] TTL=64, seq=25, ack zeroed china(http) → cam(54190) . . . more of the web page

cam(54190) → china(http) [RST] TTL=64, seq=25, ack zeroed china(http) → cam(54190) [RST] TTL=47, seq=2921, ack=25

After the client (cam54190) sends the request containing flaggable keywords, it receives 3 TCP RSTs corresponding to one request, possibly to ensure that the sender receives a reset. The RST packets received correspond to the sequence number of 1460 sent in the GET request

Technique 5: Immediate Reset of Connections

Censorship systems like GFW have blocking rules in addition to inspecting content, to suspend traffic coming from a source immediately, for a short period of time.

After sending a request with flaggable keywords (above), we see a series of packet trace, like this:

cam(54191) → china(http) [SYN]

china(http) → cam(54191) [SYN, ACK] TTL=41

cam(54191) → china(http) [ACK]

china(http) → cam(54191) [RST] TTL=49, seq=1

The reset packet received by the client is from the firewall. It does not matter that the client sends out legitimate GET requests following one “questionable” request. It will continue to receive resets from the firewall for a particular duration. Running different experiments suggests that this blocking period is variable for “questionable” requests.

Why is DNS Manipulation Difficult to Measure?

Anecdotal evidence suggests that more than 60 countries are currently impacted by control of access to information through the Internet's Domain Name System (DNS) manipulation. However, our understanding of censorship around the world is relatively limited.

What are the challenges?

Diverse Measurements

Such understanding would need a diverse set of measurements spanning different geographic regions, ISPs, countries, and regions within a single country. Since political dynamics can vary so different ISPs can use various filtering techniques and different organizations may implement censorship at multiple layers of the Internet protocol stack and using different techniques. For example, an ISP may be blocking traffic based on IP address, but another ISP may be blocking individual web requests based on keywords.

Therefore, we need widespread longitudinal measurements to understand global Internet manipulation and the heterogeneity of DNS manipulation, across countries, resolvers, and domains.

Need for Scale

At first, the methods to measure Internet censorship were relying on volunteers who were running measurement software on their own devices. Since this requires them to actually install software and do measurements, we can see that this method is unlikely to reach the scale required. There is a need for methods and tools that are independent of human intervention and participation.

Identifying the intent to restrict content access

While identifying inconsistent or anomalous DNS responses can help to detect a variety of underlying causes such as for example misconfigurations, identifying DNS manipulation is different and it requires that we detect the intent to block access to content. It poses its own challenges.

So we need to rely on identifying multiple indications to infer DNS manipulation.

Ethics and Minimizing Risks

Obviously, there are risks associated with involving citizens in censorship measurement studies, based on how different countries maybe penalizing access to censored material. Therefore it is safer to stay away from using DNS resolvers or DNS forwarders in the home networks of individual users. Instead, it is safer to rely on open DNS resolvers that are hosted in Internet infrastructure, for example within Internet service providers or cloud hosting providers).

Example Censorship Detection Systems and Their Limitations

Main censorship detection systems and their limitations

Global censorship measurement tools were created by efforts to measure censorship by running experiments from diverse vantage points. For example, CensMon used PlanetLab nodes in different countries. However, many such methods are no longer in use. One the most common systems/approaches is the OpenNet Initiative where volunteers perform measurements on their home networks at different times since the past decade. Relying on volunteer efforts make continuous and diverse measurements very difficult.

In addition, Augur (about which we will talk about next)) is a new system created to perform longitudinal global measurements using TCP/IP side channels. However, this system focuses on identifying IP-based disruptions as opposed to DNS-based manipulations.

DNS Censorship: A Global Measurement Methodology

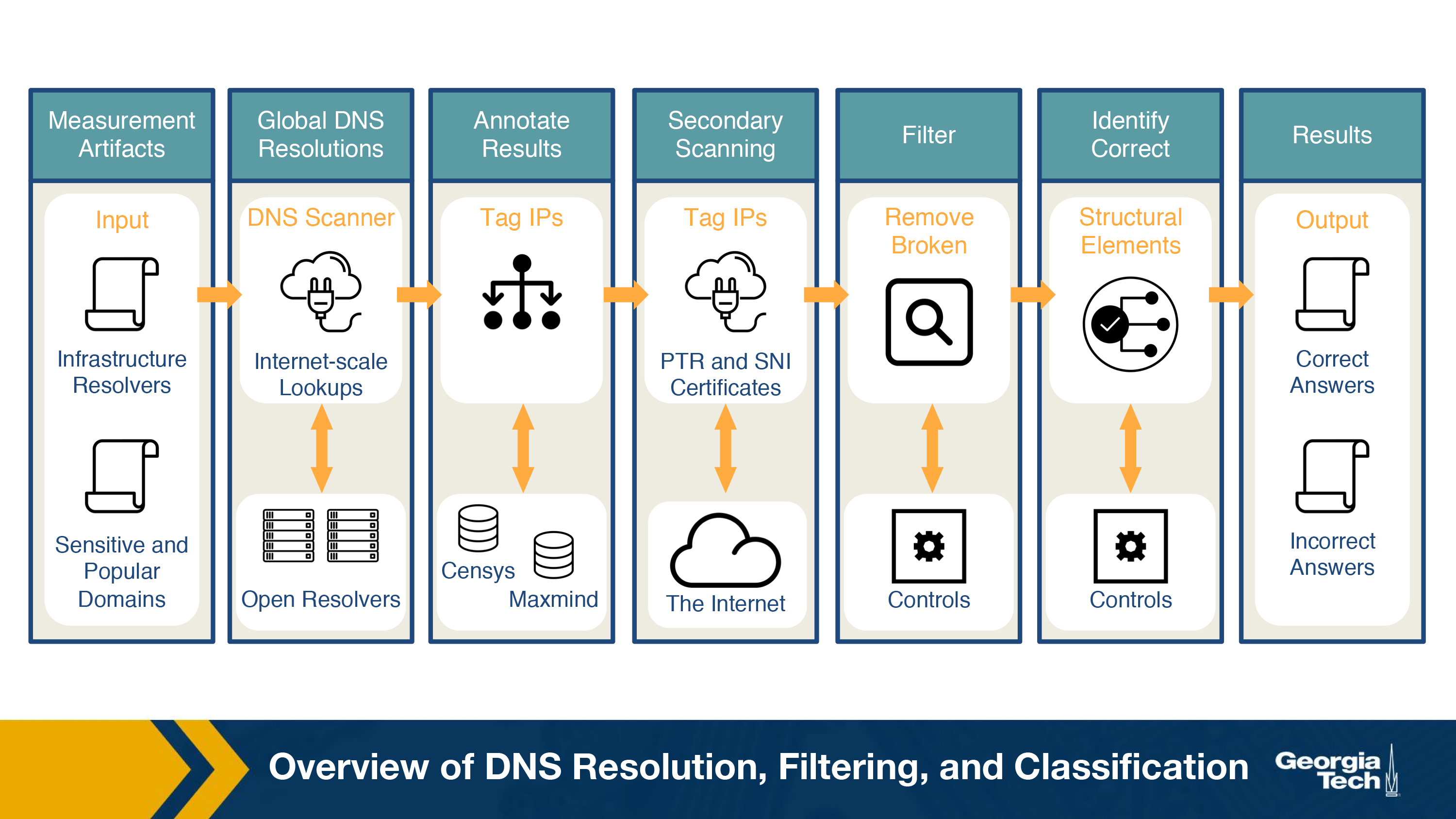

In this section, we explore a method to identify DNS manipulation via machine learning with a system called Iris. The figure below shows an overview of the identification process.

In previous sections, we discussed how the lack of diversity is an issue while studying DNS manipulation. In order to counter that, Iris uses open DNS resolvers located all over the globe. In order to avoid using home routers (which are usually open due to configuration issues), this dataset is then restricted to a few thousand that are part of the Internet infrastructure. There are two main steps associated with this process:

- Scanning the Internet's IPv4 space for open DNS resolvers

- Identifying Infrastructure DNS Resolvers

Now that we've obtained a global set of open DNS resolvers, we need to perform the measurements. The figure below shows the overall measurement process. The steps involved in this measurement process are:

- Performing global DNS queries – Iris queries thousands of domains across thousands of open DNS resolvers. To establish a baseline for comparison, the creators included 3 DNS domains which were under their control to help calculate metrics used for evaluation DNS manipulation.

- Annotating DNS responses with auxiliary information – To enable the classification, Iris annotates the IP addresses with additional information such as their geo-location, AS, port 80 HTTP responses, etc. This information is available from the Censys dataset.

- Additional PTR and TLS scanning – One IP address could host several websites via virtual hosting. So, when Censes retrieves certificates from port 443, it could differ from one retrieved via TLS's Server Name Indication (SNI) extension. This results in discrepancies that could cause IRIS to label virtual hosting as DNS inconsistencies. To avoid this, Iris adds PTR and SNI certificates.

After annotating the dataset, techniques are performed to clean the dataset, and identify whether DNS manipulation is taking place or not. Iris uses two types of metrics to identify this manipulation:

- Consistency Metrics – Domain access should have some consistency, in terms of network properties, infrastructure or content, even when accessed from different global vantage points. Using one of the domains Iris controls gives a set of high-confidence consistency baselines. Some consistency metrics used are IP address, Autonomous System, HTTP Content, HTTPS Certificate, PTRs for CDN.

- Independent Verifiability Metrics – In addition to the consistency metrics, they also use metrics that could be externally verified using external data sources. Some of the independent verifiability metrics used are: HTTPS certificate (whether the IP address presents a valid, browser trusted certificate for the correct domain name when queried without SNI) and HTTPS Certificate with SNI.

If neither metrics are satisfied, the response is said to be manipulated.

Censorship Through Connectivity Disruptions

In this topic we are talking about a different class of approach to censorship, that is based on connectivity disruptions.

The highest level of Internet censorship is to completely block access to the Internet. Intuitively, this can be done by manually disconnecting the hardware that are critical to connect to the Internet. Although this seems simple, it may not be feasible as the infrastructure could be distributed over a wide area.

A more subtle approach is to use software to interrupt the routing or packet forwarding mechanisms. Let's look at how these mechanisms would work:

- Routing disruption: A routing mechanism decides which part of the network can be reachable. Routers use BGP to communicate updates to other routers in the network. The routers share which destinations it can reach and continuously update its forwarding tables to select the best path for an incoming packet. If this communication is disrupted or disabled on critical routers, it could result in unreachability of the large parts of a network. Using this approach can be easily detectable, as it involves withdrawing previously advertised prefixes must be withdrawn or re-advertising them with different properties and therefore modifying the global routing state of the network, which is the control plane.

- Packet filtering: Typically, packet filtering is used as a security mechanism in firewalls and switches. But to disrupt a network's connectivity, packet filtering can be used to block packets matching a certain criteria disrupting the normal forwarding action. This approach can be harder to detect and might require active probing of the forwarding path or monitoring traffic of the impacted network.

Connectivity disruption can include multiple layers apart from the two methods described above. It can include DNS-based blocking, deep packet inspection by an ISP or the client software blocking the traffic, to list a few.

Connectivity Disruptions: A Case Study

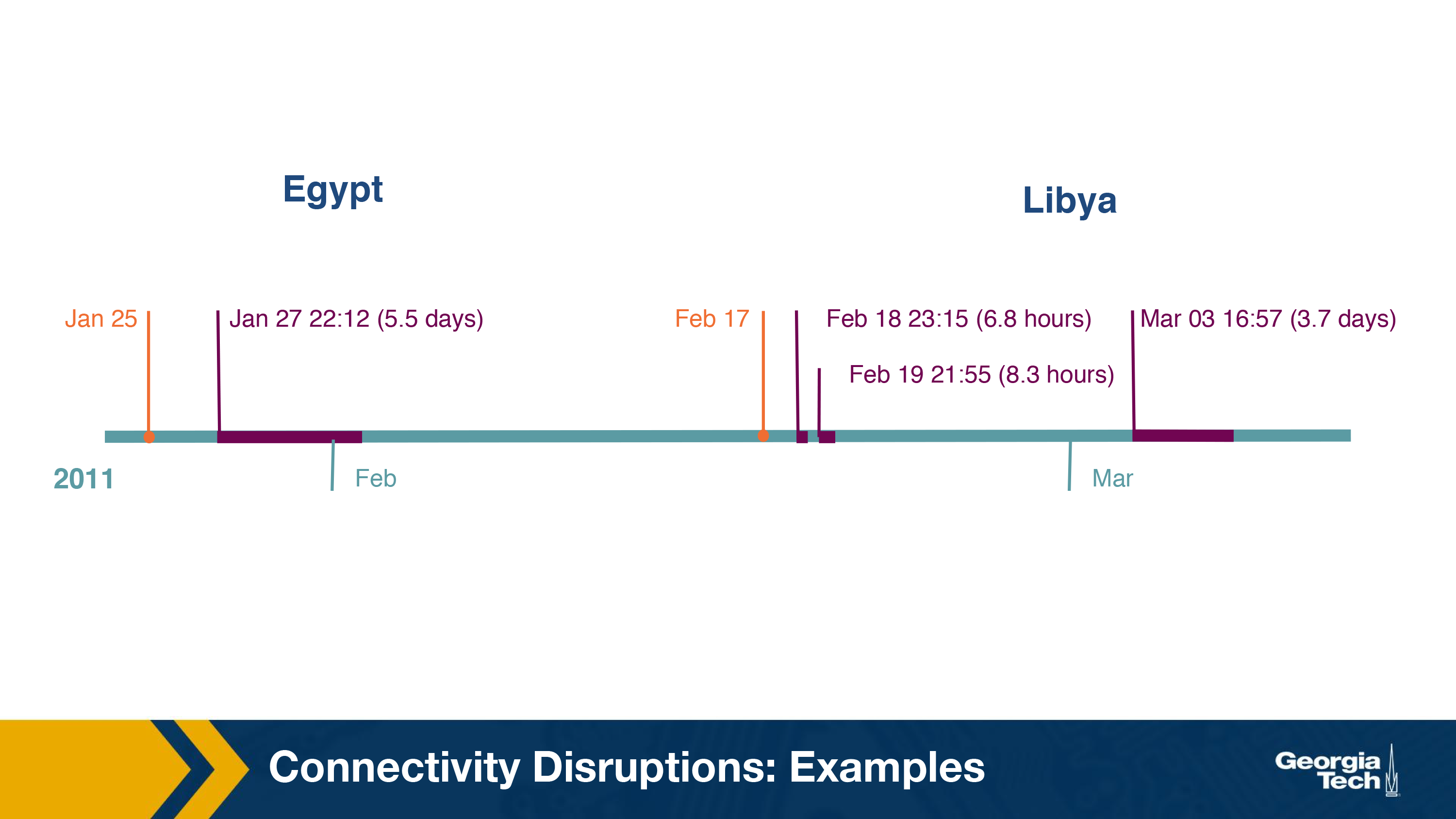

In early 2011, Internet connectivity was disabled in many North African countries as a response to political developments. Let's look at the analysis of these disruptions in two countries, Egypt and Libya.

The following figure shows the timeline of the events in the two countries.

In Egypt, there was a series of political developments. On 25th January, access to Twitter was blocked and as the political developments intensified, there was a complete shutdown of the Internet on 27th January.

In Libya, similar political developments unfolded about four days after the above incident. On February 17, Youtube was blocked to the users followed by an Internet curfew on February 18, blocking Internet connectivity till 8am in the morning. Later on March 3rd, Internet access was disabled completely for around 4 days.

To analyze these two events, the researchers gathered the following data from various sources:

-

The Internet numbering resources in or related to the countries were identified using the geolocation data:

- IP Addresses - The list of IP addresses geolocated to Egypt and Libya were determined from two sources: the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) published list and the MaxMind GeoLite Country IP geolocation database.

- AS Numbers and BGP-announced prefixes - The above IP addresses were mapped to BGP-announced prefixes and origin ASes, using publicly available BGP data during the disruption period.

- BGP Control Plane Data: The BGP updates were obtained from two major sources - Route Views Project [59] and RIPE NCC's Routing Information Service (RIS). Along with BGP updates, a periodic dump of snapshot of the control plane table was also used to track the reachability of a prefix during the period of disruption. The start and end time of the outage was also determined by observing BGP updates for the withdrawal of prefixes and when it became available again.

- Darknet Traffic: Internet background radiation (IBR) refers to unsolicited one-way traffic to unused IP addresses in the Internet. These usually indicate malicious activity on the Internet, including worms, Denial of Service attacks, etc. IBR traffic is observed using network telescopes, called darknets. The three main causes of IBR traffic are due to DoS attacks, scans and bugs and misconfiguration.

- Active forward path probing: The active macroscopic traceroute measurements and structured global IPv4 address probing during the outage were also considered in the two countries.

Analysis - Egypt

During the outage in Egypt, it was observed that all the routes to Egyptian networks were withdrawn from the Internet's global routing table. The primarily state owned Internet infrastructure of Egypt, with a small number of parties providing international connectivity and a state telecommunications provider controlling the physical connectivity, enables such manipulation of the system.

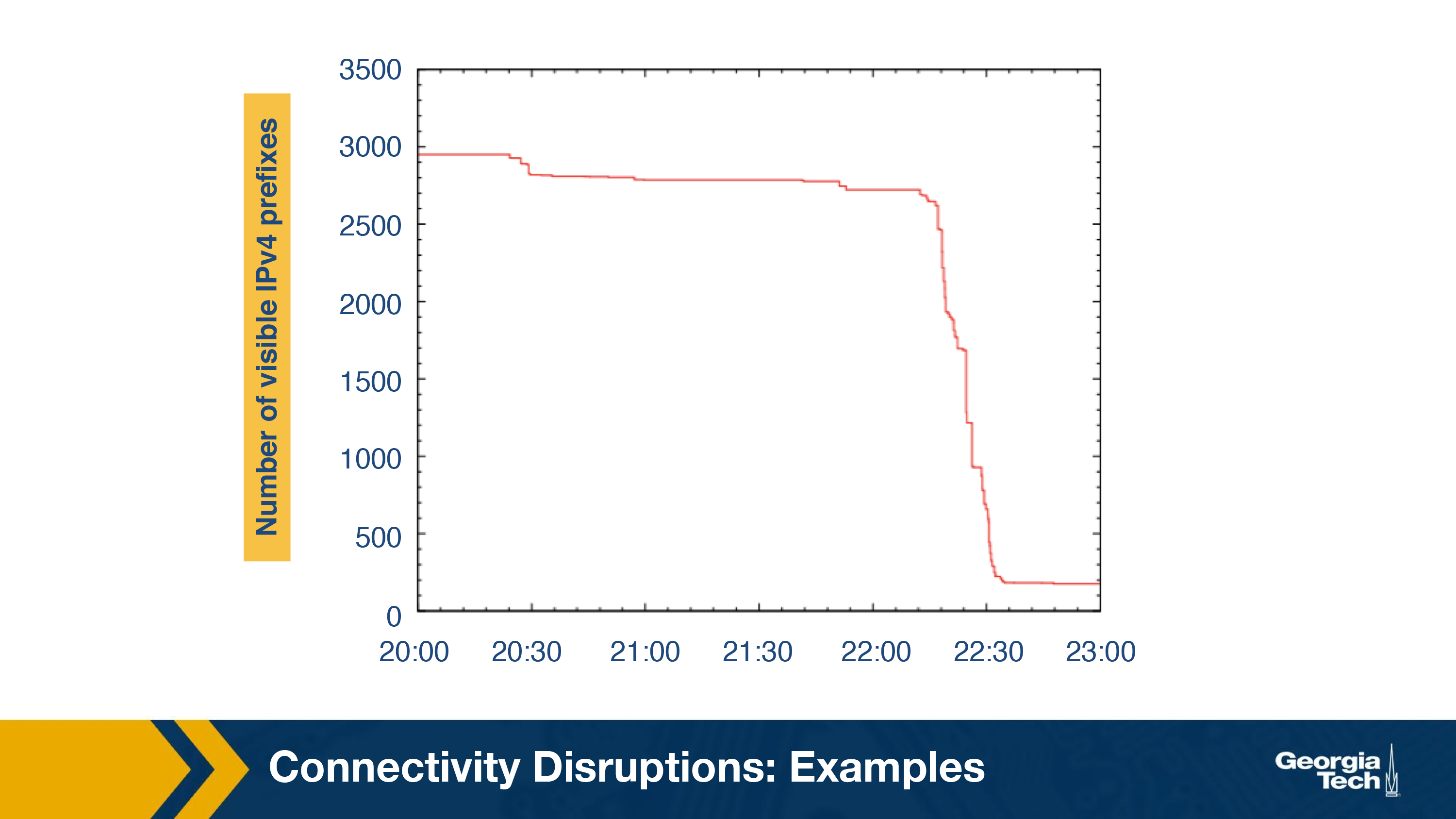

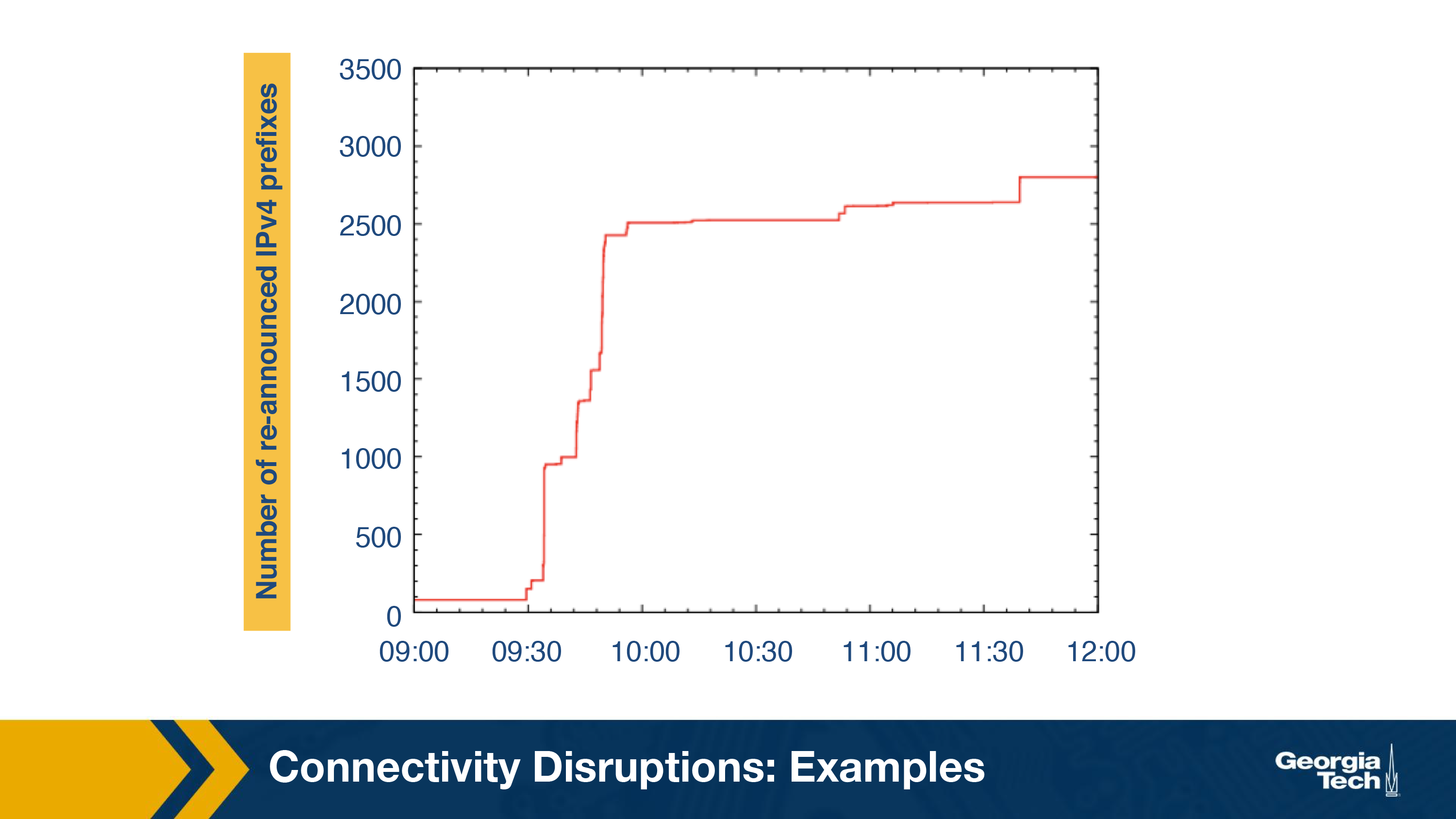

The chronological sequence of the outage determined using BGP was found to be synchronized with the reported events. A number of withdrawal routing events were observed between 27th January 22:12:00 GMT and 22:34:00 GMT, signaling the start of the outage. As shown in the graph, the number of visible IP address dropped down from 2500 to less than 500.

As expected, the restoration of Internet connectivity increased the number of re-announced IPv4 prefixes. As seen in the below graph, the number of visible prefixes went up from less than 500 to around 3000.

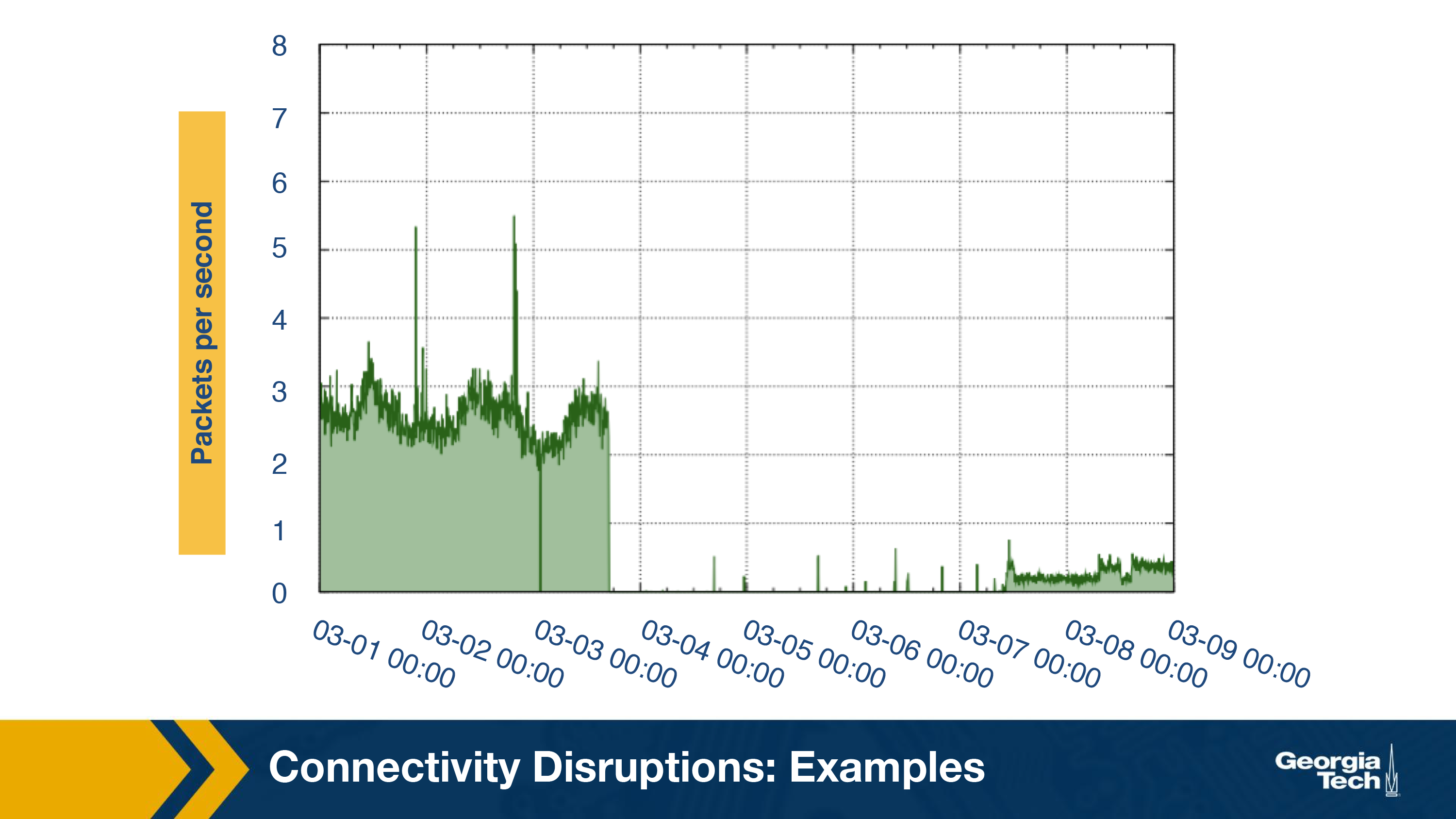

There was also a decrease in the rate of unsolicited traffic observed by darknet around 22:32:00 GMT when the outage began and an increase to the normal rate at the end of the outage. The analysis of the darknet traffic also identified DoS attacks to the Egyptian government sites.

Analysis - Libya

A single AS which is owned by the state dominates Libya's Internet infrastructure, with only two submarine cables providing international connectivity, making it easier to manipulate. Libya encountered three outages as shown in the timeline.

During the first two outages, it was observed that 12 out of the 13 delegated prefixes to Libya were withdrawn by its local telecom operator with a reasonable exception of a prefix that was controlled by an outside company. However, it was also observed that the darkest received some small traffic during the second outage suggesting that other censorship techniques might have been used.

During the third outage, it was observed that none of the BGP routes were withdrawn. Unlike the first two outages where the primary technique was BGP disruption, the third outage was caused by packet filtering. This can be concluded by the small amount of traffic observed (shown in the below graph) by darknet that is consistent with the behavior of packet filtering.

Connectivity disruptions: Detection

As we saw in a previous section, obtaining a view of global censorship can be challenging due to a variety of reasons. In this section, we focus on a system, Augur, which uses a measurement machine to detect filtering between hosts.

The system aims to detect if filtering exists between two hosts, a reflector and a site. A reflector is a host which maintains a global IP ID. A site is a host that may be potentially blocked. To identify if filtering exists, it makes use of a third machine called the measurement machine.

IP ID

The strategy used by Augur takes advantage of the fact that any packet that is sent by a host is assigned a unique 16-bit IP identifier (“IP ID”), which the destination host can use to reassemble a fragmented packet. This IP ID should be different for the packets that are generated by the same host. Although there are multiple methods available to determine the IP ID of a packet (randomly, per-connection counter, etc.), maintaining a single global counter is the most commonly used approach. The global counter is incremented for each packet that is generated and helps in keeping track of the total number of packets generated by that host. Using this counter, we can determine if and how many packets are generated by a host.

In addition to the IP ID counter, the approach also leverages the fact that when an unexpected TCP packet is sent to a host, it sends back a RST (TCP Reset) packet. It also assumes there is no complex factors involved such as cross-traffic or packet loss. Let's look at two important mechanisms used by the approach:

Probing

Probing is a mechanism to monitor the IP ID of a host over time. We use the measurement machine to observe the IP ID generated by the reflector. To do so, the measurement machine sends a TCP SYN-ACK to the reflector and receives a TCP RST packet as the response. The RST packet received would contain the latest IP ID that was generated by the reflector. Thus, the measurement machine can track the IP ID counter of the reflector at any given point.

Perturbation

This is a mechanism which forces a host to increment its IP ID counter by sending traffic from different sources such that the host generates a response packet. The flow here is as follows:

- The measurement machine sends a spoofed TCP SYN packet to the site with source address set to the reflector's IP address.

- The site responds to the reflector with a TCP SYN-ACK packet.

- The reflector returns a TCP RST packet to the site while also incrementing its global IP ID counter by 1.

Now that we know how to probe and perturb the IP ID values at a host, let's analyze the different possible scenarios. Let the initial IP ID counter of the reflector be 5.

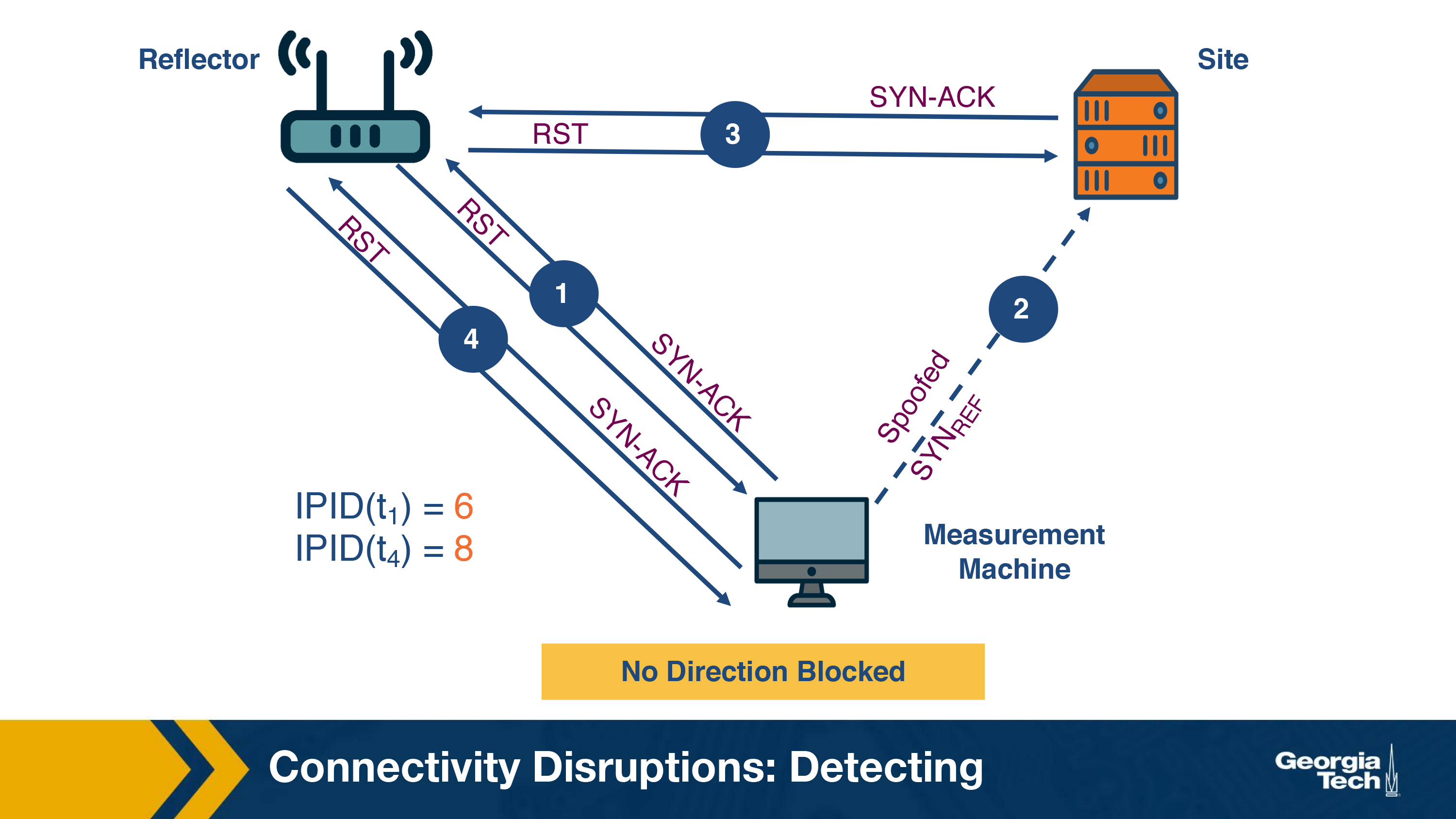

No filtering

Assume a scenario where there's no filtering as shown in the below figure.

The sequence of events is as follows:

- The measurement machine probes the IP ID of the reflector by sending a TCP SYN-ACK packet. It receives a RST response packet with IP ID set to 6 (IPID (t1)).

- Now, the measurement machine performs perturbation by sending a spoofed TCP SYN to the site.

- The site sends a TCP SYN-ACK packet to the reflector and receives a RST packet as a response. The IP ID of the reflector is now incremented to 7.

- The measurement machine again probes the IP ID of the reflector and receives a response with the IP ID value set to 8 (IPID (t4)).

The measurement machine thus observes that the difference in IP IDs between steps 1 and 4 is 2 and infers that communication has occurred between the two hosts.

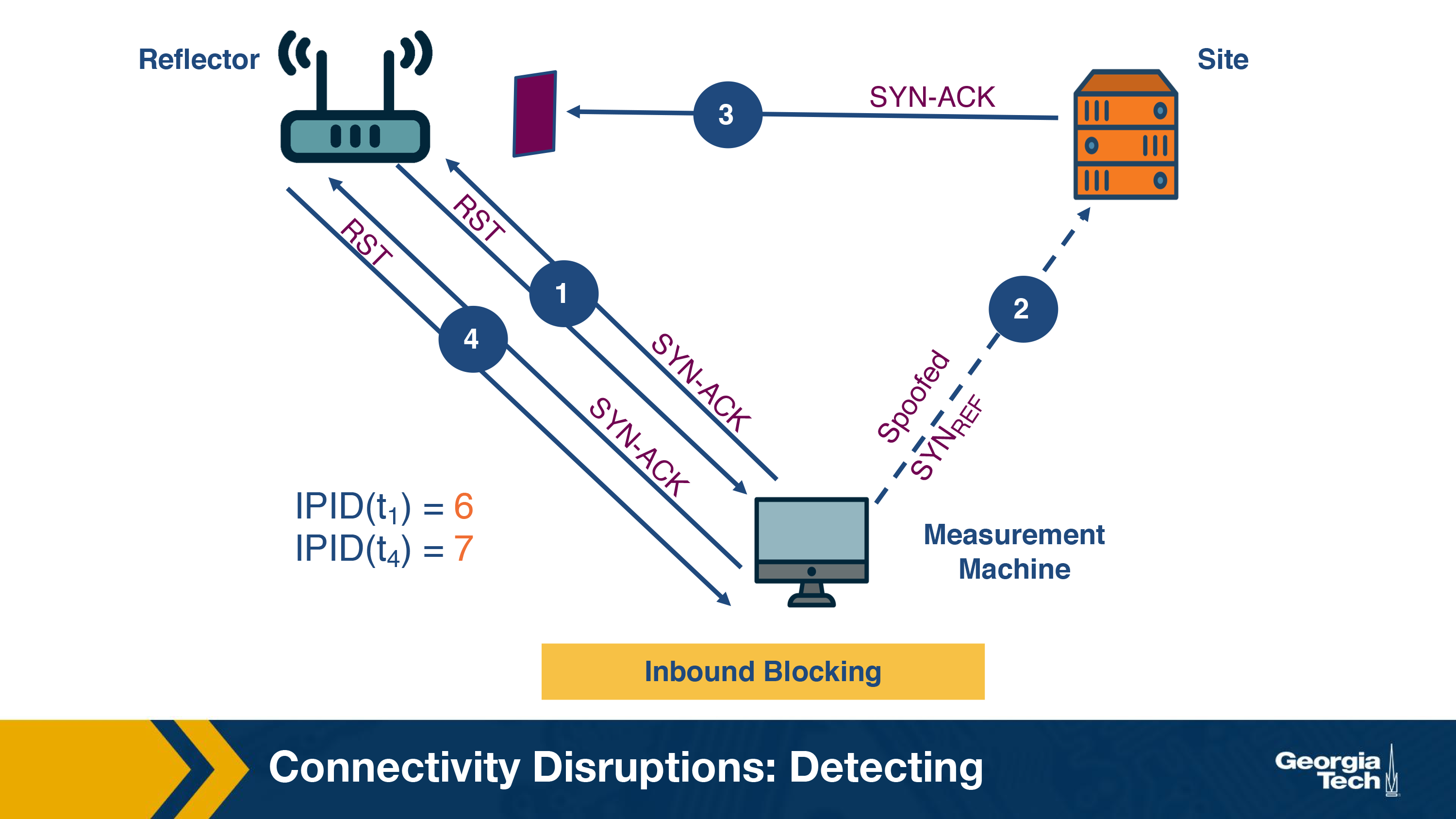

Inbound blocking

The scenario where filtering occurs on the path from the site to the reflector is termed as inbound blocking. In this case, the SYN-ACK packet sent from the site in step 3 does not reach the reflector. Hence, there is no response generated and the IP ID of the reflector does not increase. The returned IP ID in step 4 will be 7 (IPID(t4)) as shown in the figure. Since the measurement machine observes the increment in IP ID value as 1, it detects filtering on the path from the site to the reflector.

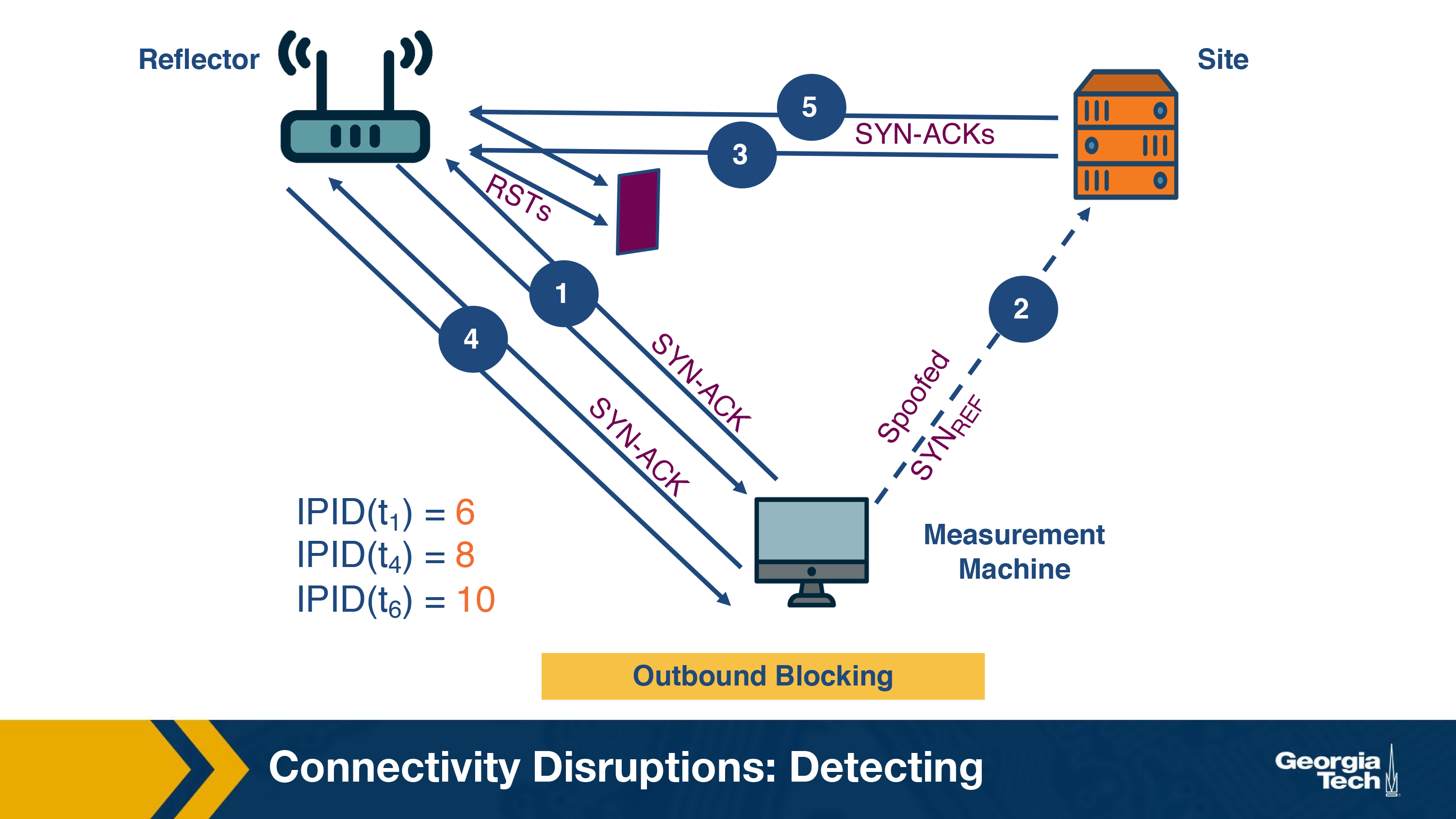

Outbound blocking

Outbound blocking is the filtering imposed on the outgoing path from the reflector. Here, the reflector receives the SYN-ACK packet and generates a RST packet. As per our example, in step 3, the IP ID increments to 7. However, the RST packet does not reach the site. When the site doesn't receive a RST packet, it continues to resend the SYN-ACK packets at regular intervals depending on the site's OS and its configuration. This is shown in step 5 of the figure. It results in further increment of the IP ID value of the reflector. In step 6, the probe by the measurement machine reveals the IP ID has again increased by 2, which shows that retransmission of packets has occurred. In this way, outbound blocking can be detected.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy