Computer Networks

Autonomous System Relationship and Interdomain Routing

28 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Autonomous System Relationship and Interdomain Routing

Autonomous Systems and Internet Interconnection

The Internet is a complex ecosystem. Today's Internet is a complex ecosystem that is built of a network of networks. The basis of this ecosystem includes Internet Service Providers (ISPs), Internet Exchange Points (IXPs), and Content Delivery Networks (CDNs).

Let's talk more about each type of these networks:

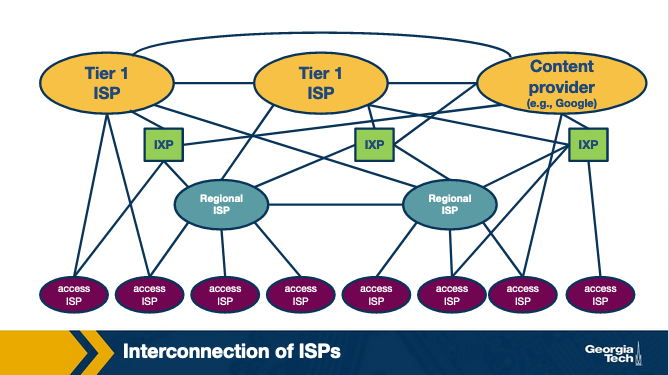

First, ISPs can be categorized into three tiers or types: access ISPs (or Tier-3), regional ISPs (or Tier-2) and large global scale ISPs (or Tier-1). There is a dozen of large scale Tier-1 ISPs that operate at a global scale, and essentially they form the “backbone” network over which smaller networks can connect. Some example Tier-1 ISPs include AT&T, NTT, Level-3, and Sprint. In turn regional ISPs connect to Tier-1 ISPs, and smaller access ISPs connect to regional ISPs.

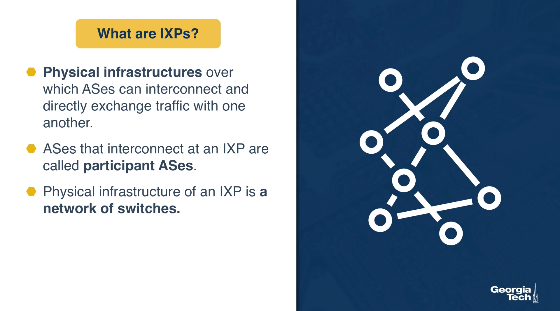

Second, IXPs are interconnection infrastructures, which provide the physical infrastructure, where multiple networks (e.g., ISPs and CDNs) can interconnect and exchange traffic locally. As of 2019, there are approximately 500 IXPs around the world.

Third, CDNs are networks that are created by content providers with the goal of having greater control of how the content is delivered to the end-users, and also to reduce connectivity costs. Some example CDNs include Google and Netflix. These networks have multiple data centers - and each one of them may be housing hundreds of servers – that are distributed across the world.

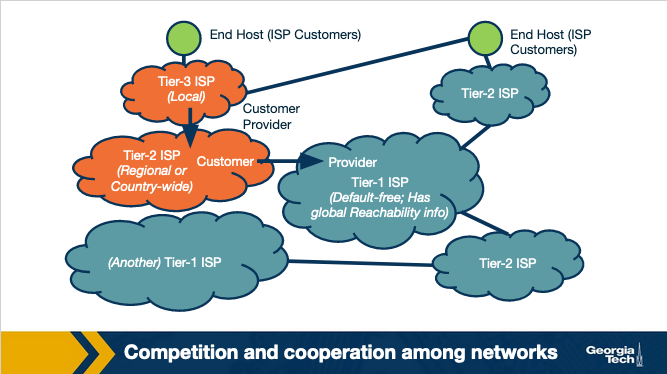

Competition and cooperation among networks. This ecosystem we just described, forms a hierarchical structure, since smaller networks (e.g., access ISPs) connect to larger networks (e.g., Tier-3 ISPs). In other words, an access ISP receives Internet connectivity becoming the customer of a larger ISP. In this case, the larger ISP becomes the provider of the smaller ISP. This leads to competition at every level of the hierarchy. For example, Tier-1 ISPs compete with each other, and the same is true for regional ISPs which compete with each other as well. But, at the same time, competing ISPs need to cooperate to provide global connectivity to their respective customer networks. ISPs deploy multiple interconnection strategies depending on the number of customers in their network and also the geographical location of these networks.

More interconnection options in the Internet ecosystem. To complete the picture of today's Internet interconnection ecosystem we note that ISPs may also connect through Points of Presence (PoPs), multihoming and peering. PoPs are one (or more) routers in a provider's network, which can be used by a customer network to connect to that provider. Also, an ISP may choose to multi-home by connecting to one or more provider networks. Finally, two ISPs may choose to connect through a settlement-free agreement where neither network pays the other to send traffic to one another directly.

The Internet topology: hierarchical vs flat. As we said, this ecosystem we just described, forms a hierarchical structure, especially in the earlier days of the Internet. But, its important to note that as the Internet has been evolving and especially with the dominant presence of IXPs, and CDNs, the structure has been morphing from hierarchical to flat.

Autonomous Systems. Each of the types of networks that we talked about above (e.g., ISPs and CDNs) may operate as an Autonomous System (AS). An AS is a group of routers (including the links among them) that operate under the same administrative authority. An ISP, for example, may operate as a single AS or it may operate through multiple ASes. Each AS implements its own set of policies, makes its own traffic engineering decisions and interconnection strategies, and also determines how the traffic leaves and enters the network.

Protocols for routing traffic between and within ASes. The border routers of the ASes use the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) to exchange routing information with one another. In contrast, the Internal Gateway Protocols (IGPs), operate within an AS and they are focused on “optimizing a path metric” within that network. Example IGPs include Open Shortest Paths First (OSPF), Intermediate System - Intermediate System (IS-IS), Routing Information Protocol (RIP), E-IGRP. In this lesson, we will focus on BGP.

Autonomous System Business Relationships

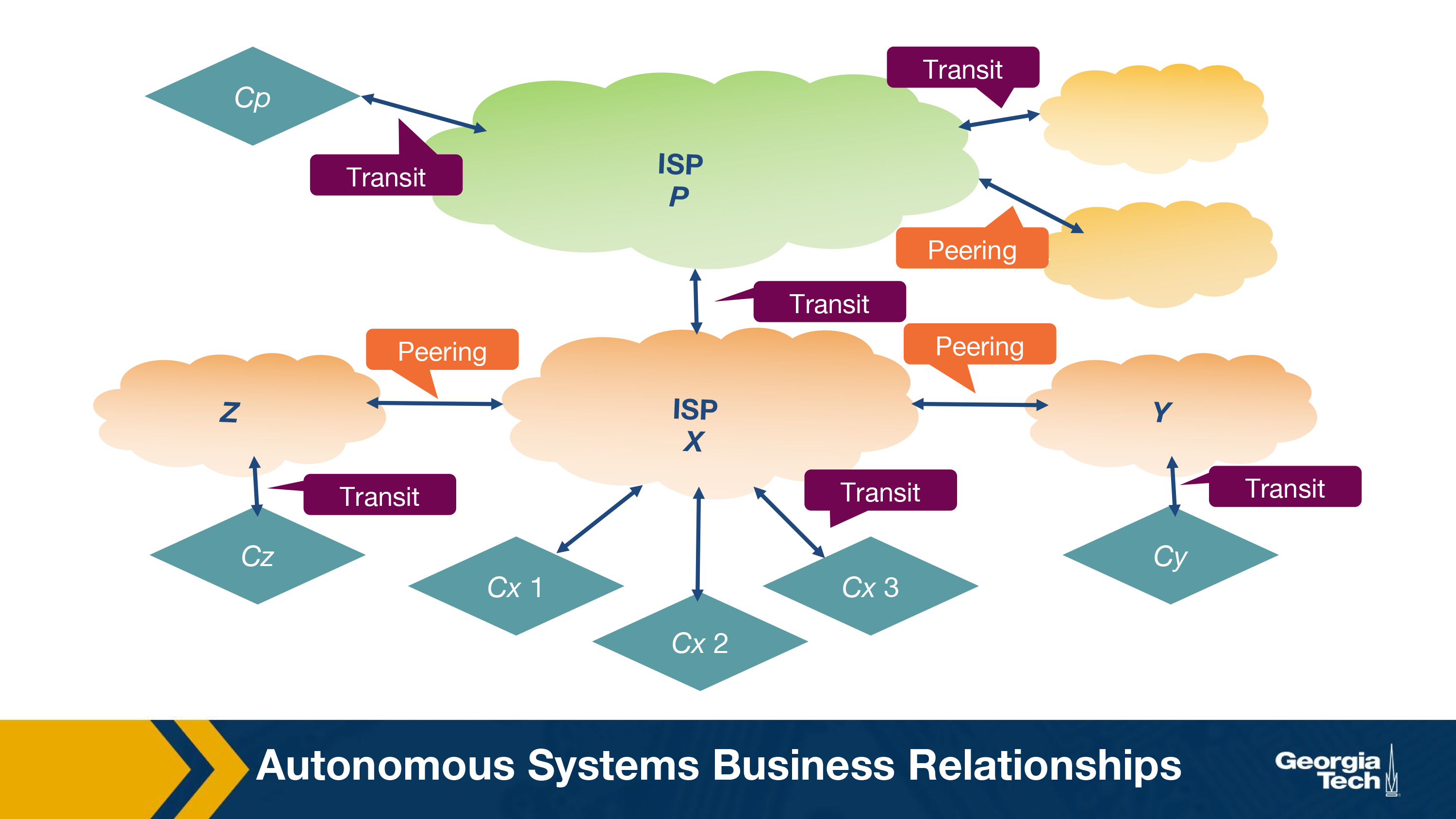

In this topic, we will talk about the prevalent forms of business relationships between autonomous systems:

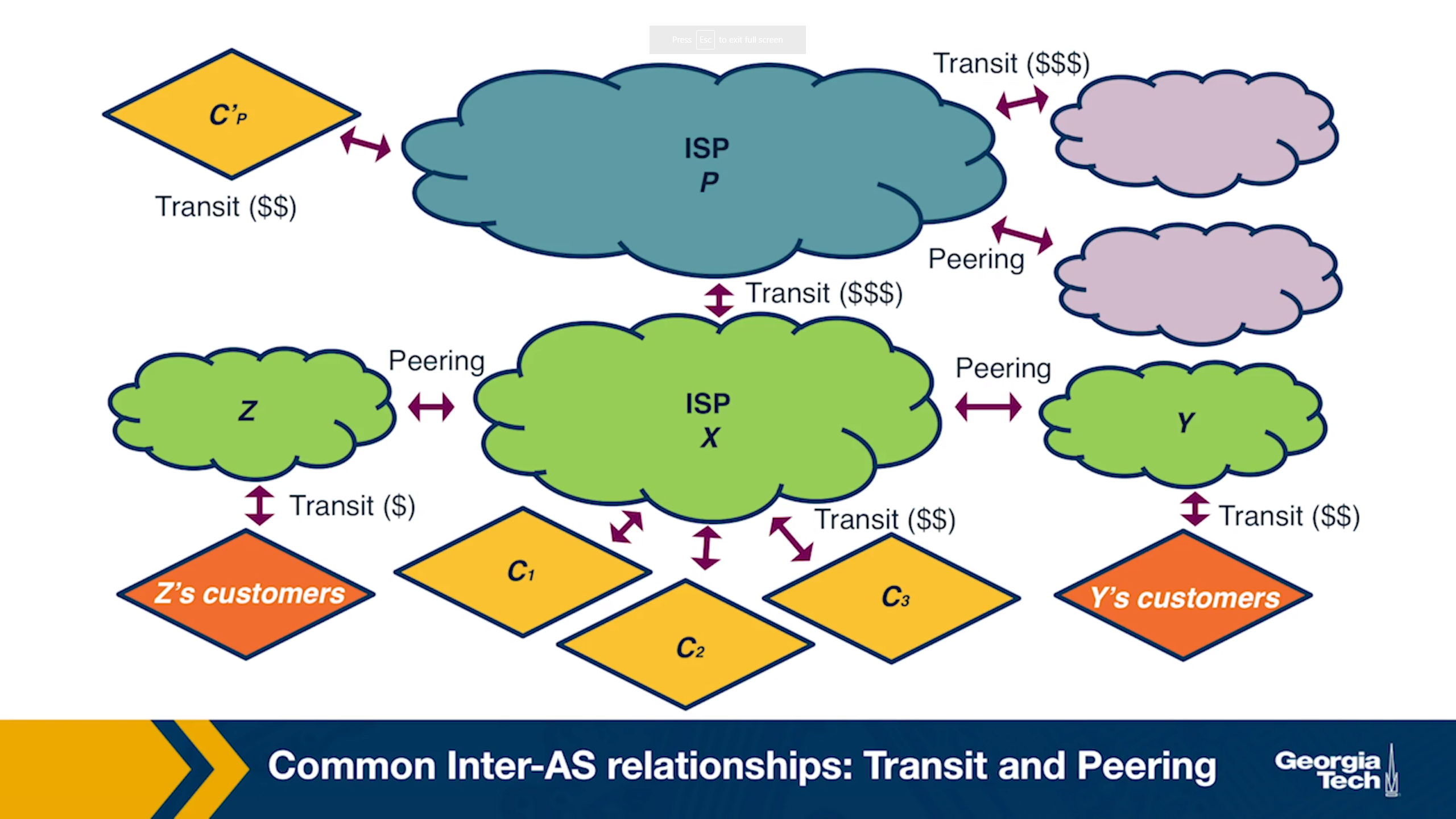

- Provider-Customer relationship (or transit). This relationship is based on a financial settlement which determines how much the customer will pay the provider, so the provider forwards the customer's traffic to destinations found in the provider's routing table (including the opposite direction of the traffic as well).

- Peering relationship. In a peering relationship, two ASes share access to a subset of each other's routing tables. The routes that are shared between two peers are often restricted to the respective customers of each one. The agreement holds provided that the traffic exchanged between the two peers is not highly asymmetric. Peering relationships are formed between Tier-1 ISPs but also between smaller ISPs. In the case of Tier-1 ISPs, the two peers need to be of similar size and handle similar amounts of traffic. Otherwise, the larger ISP would lack the incentive to enter a peering relationship with a smaller size ISP. In the case of peering between two smaller size ISPs, the incentive they both have is to save the money they would pay their providers by directly forwarding to each other their traffic, provided that there is a significant amount of traffic that is destined for each other (or each other's customers).

How do providers charge customers?

While peering allows networks to get their traffic forwarded without cost, provider ASes have a financial incentive to forward as much of their customers' traffic as possible. One major factor that determines a provider's revenue is the data rate of an interconnection. A provider usually charges in one of two ways:

- Based on a fixed price given that the bandwidth used is within a predefined range.

- Based on the bandwidth used. The bandwidth usage is calculated based on periodic measurements, e.g., on five min intervals. The provider then charges by taking the 95th percentile of the distribution of the measurements.

Sometimes in practice, we observe complex routing policies. In some cases, the driving force behind these policies is to increase the amount of traffic from a customer to its provider, and therefore increase the providers' revenue.

BGP Routing Policies: Importing and Exporting Routes

In the previous topic, we talked about AS business relationships. AS business relationships drive an AS' routing policies and influence which routes an AS needs to import or export. In this topic, we will talk about why it matters which routes an AS imports/exports.

Exporting Routes

Deciding which routes to export is an important decision with business and financial implications. This is the case because, advertising a route for a destination to a neighboring AS, means that this route may be selected by that AS and traffic will start to flow through. Deciding which routes to advertise is a policy decision and it is implemented through route filters; route filters are essentially rules that determine which routes an AS will allow to advertise to other neighboring ASes.

Let's look at the different types of routes that an AS (let's call it X) decides whether to export:

- Routes learned from customers. These are the routes that X receives as advertisements from its customers. Since provider X is getting paid to provide reachability to a customer AS, it makes sense that X wants to advertise these customer routes to as many other neighboring ASes as possible. This will likely cause more traffic towards the customer (through X) and hence more revenue to X.

- Routes learned from providers. These are the routes that X receives as advertisements from its providers. Advertising these routes doesn't make sense, since X does not have the financial incentive to carry traffic for its provider's routes. These routes are withheld from X's peers and other X's providers, but they are advertised to X's customers.

- Routes learned from peers. These are routes that X receives as advertisements from its peers. As we saw earlier, it doesn't make sense for X to advertise to a provider A the routes that it receives from another provider B. Because in that case, these providers A and B are going to use X to reach the advertised destinations without X making revenue. The same is true for the routes that X learns from peers.

Importing Routes

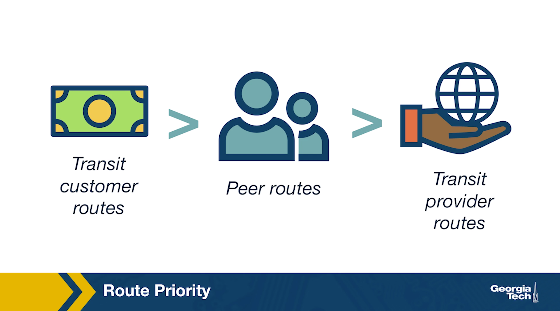

Similarly as exporting, ASes are selective about which routes to import based, primarily, on which neighboring AS advertises them and what type of business relationship is established. An AS receives route advertisements from its customers, providers and peers.

When an AS receives multiple route advertisements towards the same destination, from multiple ASes, then it needs to rank the routes before selecting which one to import. The routes that are preferred first are the customer routes, then the peer routes and finally the provider routes. The reasoning behind this ranking is that an AS...

- wants to ensure that routes towards its customers do not traverse other ASes unnecessarily generating costs

- uses routes learned from peers since these are usually “free” (under the peering agreement)

- and finally resorts to import routes learned from providers as these will add to costs

BGP and Design Goals

In the previous topics, we talked about importing and exporting routes. In the following topics, we will learn how the default routing protocol - Border Routing Protocol or BGP - is used to implement routing policies.

Let's first start with the design goals of the BGP protocol:

Scalability: As the size of the Internet grows, the same is true for the number of ASes, the number of prefixes in the routing tables, the network churn, and the BGP traffic exchanged between routers. One of the design goals of BGP is to manage the complications of this growth, while achieving convergence in reasonable timescales and providing loop-free paths.

Express routing policies: BGP has defined route attributes that allow autonomous systems to implement policies (which routes to import and export), through route filtering and route ranking. Each ASes routing decisions can be kept confidential, and each AS can implement them independently of one another.

Allow cooperation among autonomous systems: Each individual AS can still make local decisions (which routes to import and export) while keeping these decisions confidential from other ASes.

Security: was not included in the original design goals for BGP. But as the complexity and size of the Internet has been increasing, so is the need to provide security measures. We notice an increasing need for protection against malicious attacks, misconfigurations or faults, but also their early detection. These vulnerabilities still cause routing disruptions and connectivity issues for individual hosts, networks and sometimes even entire countries. There have been several efforts to enhance BGP security ranging from protocols (eg S-BGP), additional infrastructure (eg registries to maintain up to date information about which ASes own which prefixes ASes), public keys for ASes, etc. Also, there has been extensive research work to develop machine learning based approaches and systems. But these solutions have not been widely deployed or adopted due to multiple reasons that include difficulties to transition to new protocols and lack of incentives.

BGP Protocol Basics

In this topic, we will review some of the basics of the BGP protocol.

BGP session. A pair of routers, known as BGP peers, exchange routing information over a semi-permanent TCP port connection called a BGP session. To begin a BGP session a router will send an OPEN message to another router. Then the sending and receiving router will send each other announcements from their individual routing tables. Depending on the number of routes being exchanged, this can take from seconds up to several minutes.

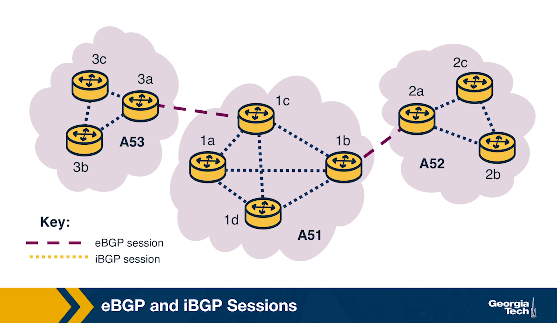

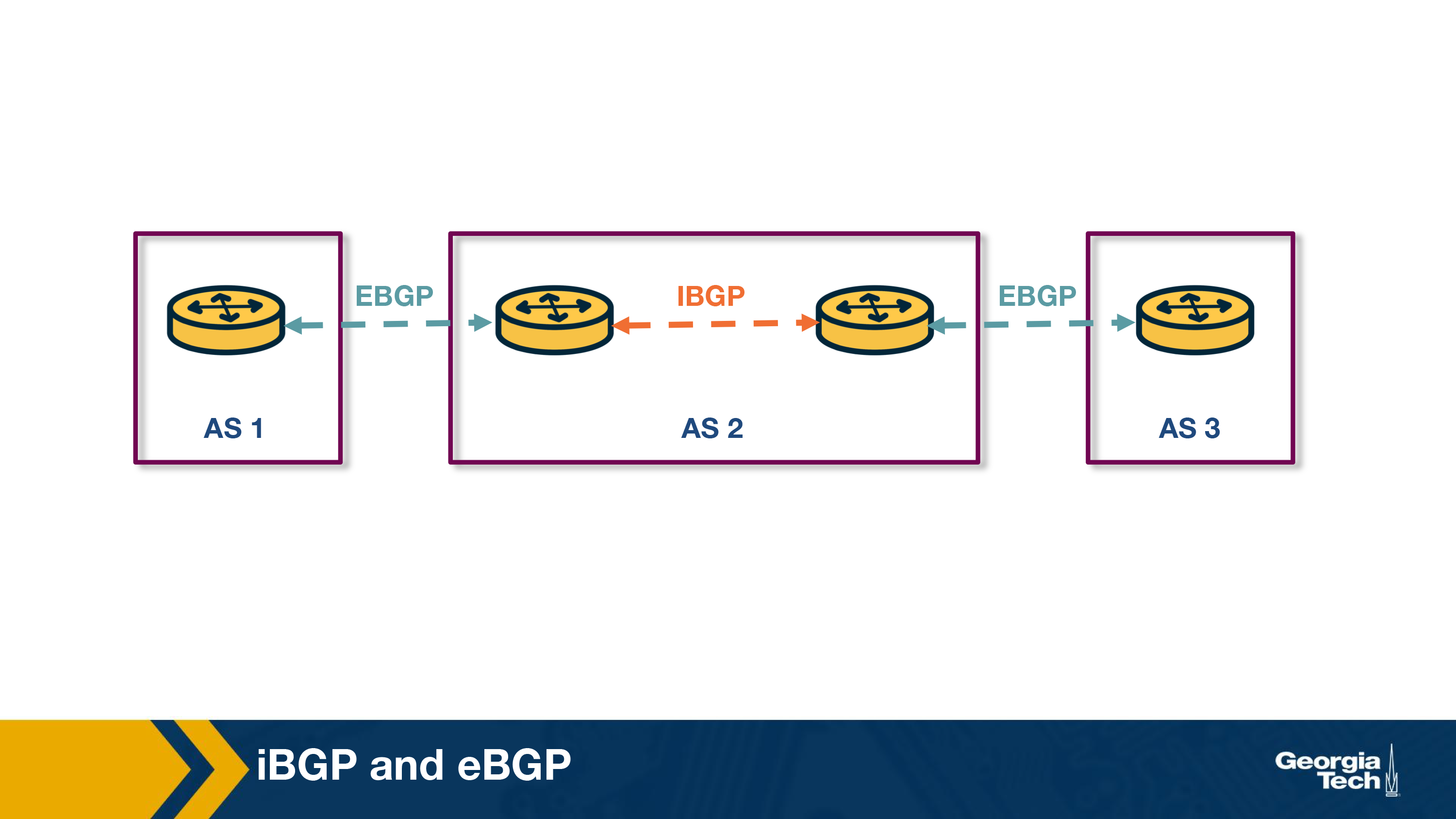

A BGP session between a pair of routers in two different ASes is called external BGP (eBGP) session, and a BGP session between routers that belong to the same AS is called internal BGP (iBGP) session.

In the following diagram, we can see 3 different ASes along with iBGP (e.g., between 3c and 3a) and eBGP (e.g., between 3a and 1c) sessions between their border routers.

BGP messages. After a session is established between BGP peers, the peers can exchange BGP messages to provide reachability information and enforce routing policies. We have two types of BGP messages:

UPDATES

- Announcements: These messages advertise new routes and updates to existing routes. They include several standardized attributes.

- Withdrawals: These messages are sent when a previously announced route is removed. This could be due to some failure or due to a change in the routing policy.

KEEPALIVE

- These messages are exchanged to keep a current session going.

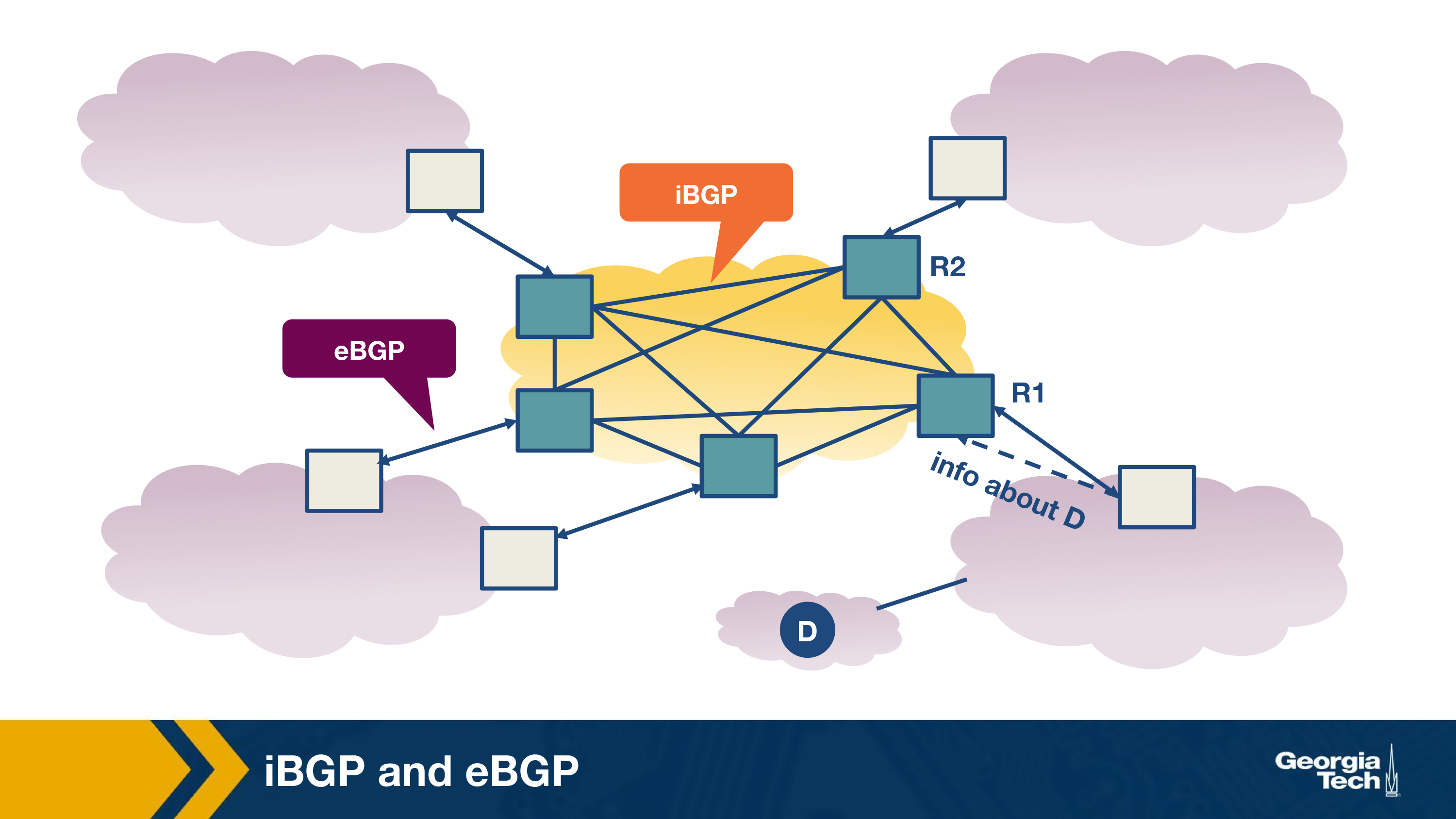

BGP prefix reachability. In the BGP protocol, destinations are represented by IP Prefixes. Each prefix represents a subnet or a collection of subnets that an AS can reach. Gateway routers running eBGP advertise the IP Prefixes they can reach according to the AS's specific export policy to routers in neighboring ASes. Then, using separate iBGP sessions, the gateway routers disseminate these routes for external destinations, to other internal routers according to the AS's import policy. Internal routers run iBGP to propagate the external routes to other internal iBGP speaking routers.

Path Attributes and BGP Routes. In addition to the reachable IP prefix field, advertised BGP routes consist of a number of BGP attributes. Two notable attributes are AS-PATH and NEXT-HOP.

AS-PATH

- Each AS, as identified by the AS's autonomous system number (ASN), that the route passes through is included in the AS-PATH. This attribute is used to prevent loops and to choose between multiple routes to the same destination, the route with the shortest path.

NEXT-HOP

- This attribute refers to the IP address (interface) of the next-hop router along the path towards the destination. Internal routers use the field to store the IP address of the border router. Internal BGP routers will have to forward all traffic bound for external destinations through the border router. If there is more than one such router on network and each advertises a path to the same external destination, NEXT-HOP allows the internal router to store in the forwarding table the best path according to the AS routing policy.

iBGP and eBGP

In the previous topic we saw that we have two flavors of BGP: eBGP (for sessions are between border routers of neighboring ASes) and iBGP (for sessions between internal routers of the same AS).

Both protocols are used to disseminate routes for external destinations.

The eBGP speaking routers learn routes to external prefixes and they disseminate them to all routers within the AS. This dissemination is happening with iBGP sessions. For example, as we see in the figure below, the border routers of AS1, AS2, and AS3 establish eBGP sessions to learn external routes. Inside AS2, these routes are disseminated using iBGP sessions.

Also, we note that the dissemination of routes within the AS is done by establishing a full mesh of iBGP sessions between the internal routers. Each eBGP speaking router has an iBGP session with every other BGP router in the AS, so that it can send updates about the routes it learns (over eBGP).

Finally, we note that iBGP is not another IGP-like protocol (eg RIP or OSPF). IGP-like protocols are used to establish paths between the internal routers of an AS based on specific costs within the AS. In contrast, iBGP is only used to disseminate external routes within the AS.

BGP Decision Process: Selecting Routes at a Router

As we already discussed in earlier topics ASes are operated and managed by different administrative authorities, and they can operate with different business goals, and network conditions (eg volumes of traffic). Of course, all these factors can affect the BGP policies for each AS independently.

Still, routers follow the same process to select routes. Let's zoom into what is happening as the routers exchange BGP messages to select routes.

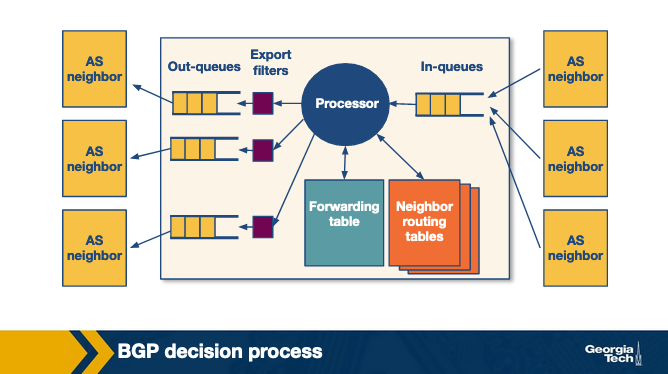

Conceptually, we can consider the model of a router as in the figure above (Reference: https://www.cc.gatech.edu/home/dovrolis/Papers/bgp-scale-conext08.pdf). A router receives incoming BGP messages and processes them. When a router receives advertisements, first it applies the import policies to exclude routes entirely from further consideration.

Then the router implements the decision process to select the best routes that reflect the policy in place. The new selected routes are installed in the forwarding table. Finally, the router decides which neighbors to export the route to, by applying the export policy.

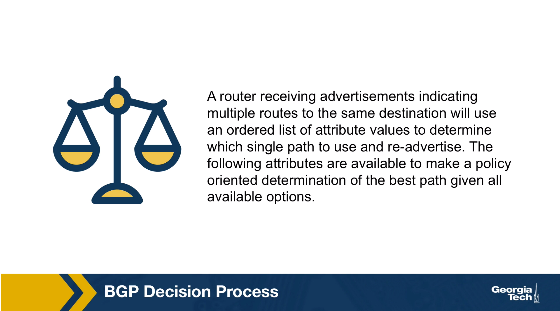

The router's decision process

Let's take a look at the router's decision process. Now, let's suppose that a router receives multiple route advertisements to the same destination. How does the router choose which route to import? In a nutshell, the decision process is how the router compares routes, by going through the list of attributes in the route advertisements. In the simplest scenario, where there is no policy in place (meaning it doesn't matter which route will be imported), the router uses the attribute of the pathlength to select the route with the fewest number of hops. But in practice, this simple scenario is rarely the case.

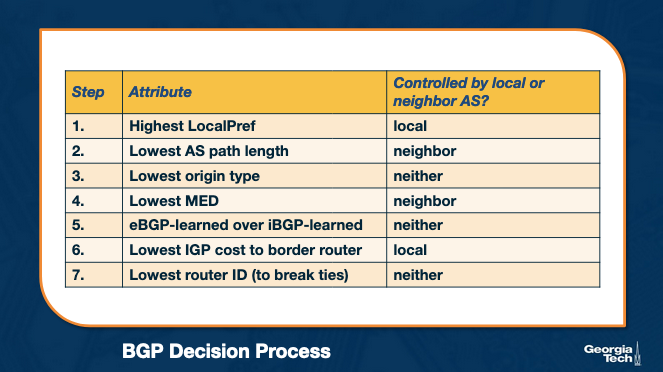

A router compares a pair of routes, by going through the list of attributes - as shown in the figure below. For each attribute, it selects the route with the attribute value that will help apply the policy. If for a specific attribute, the values are the same, then it goes to the next attribute.

Let's focus on two attributes, LocalPref and MED (Multi-Exit Discriminator) , and let's see how we can use them to influence the decision process.

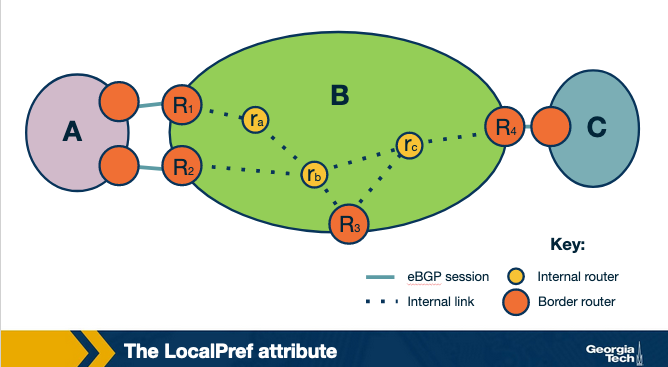

Influencing the route decision using the LocalPref. The LocalPref attribute is used to prefer routes learned through a specific AS over other ASes. For example, suppose AS B learns of a route to the same destination x via A and C. If B prefers to route its traffic through A, due to peering or business, it can assign a higher LocalPref value to routes it learns from A. And therefore, by using LocalPref, AS B can control where the traffic exits the AS. In other words, it will influence which routers will be selected as exit points for the traffic that leaves the AS (outbound traffic).

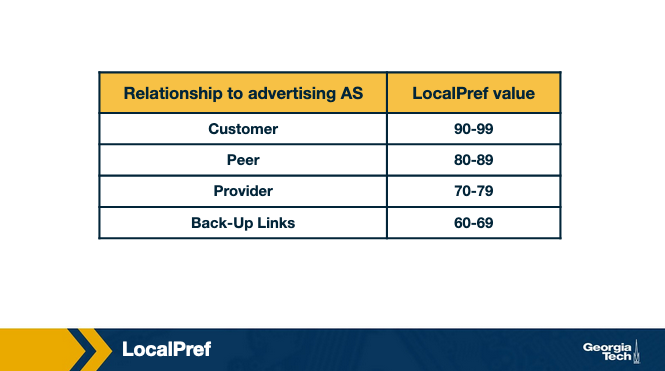

As we saw earlier in this lesson, an AS ranks the routes it learns by preferring first the routes learned from its customers, then the routes learned from its peers and finally the routes learned from its providers. An operator can assign a non-overlapping range of values to the LocalPref attribute according to the type of relationship. So assigning different LocalPref ranges will influence which routes are imported. For example, there may be the following scheme in place, to reflect the business relationships:

Influencing the route decision using the MED attribute. The MED (Mutli-Exit Discriminator) value is used by ASes connected by multiple links to designate which of those links are preferred for inbound traffic. For example, the network operator of AS B will assign different MED values to its routes advertised to AS A through R1 and different MED values to its routes advertised through R2. As a result of different MED values for the same routes, AS A will be influenced to choose R1 to forward traffic to AS B, if R1 has lower MED value, and if all other attributes are equal.

We have seen in the previous topics that an AS does not have an economic incentive to export routes that it learns from providers or peers to other providers or peers. An AS can reflect this by tagging routes with a MED value to “staple” the type of business relationship. Also, an AS filters routes with specific MED values before exporting them to other ASes. We note that influencing the route exports will also affect how the traffic enters an AS (the routers that are entry points for the traffic that enters the AS).

So, where/how are the attributes controlled? The attributes are set either: a) locally by the AS (eg LocalPref), b) by the neighboring AS (eg MED), or c) they are set by the protocol (eg if a route is learned through eBGP or iBGP).

Challenges with BGP: Scalability and Misconfigurations

Unfortunately, the BGP protocol in practice can suffer from two major limitations: misconfigurations and faults. A possible misconfiguration or an error can result in an excessively large number of updates which in turn can result in route instability, router processor and memory overloading, outages, and router failures.

One way that ASes can help to reduce the risk that these events will happen is by limiting the routing table size and also by limiting the number of route changes.

An AS can limit the routing table size using filtering. For example, long (very specific) prefixes can be filtered to encourage route aggregation. Routers can limit the number of prefixes that are advertised from a single source on a per-session basis. Some small ASes also have the option to configure default routes into their forwarding tables. ASes can likewise protect other ASes by using route aggregation and exporting less specific prefixes where possible.

Also, an AS can limit the number of routing changes, specifically limiting the propagation of unstable routes, by using a mechanism known as flap damping. To apply this technique, an AS will track the number of updates to a specific prefix over a certain amount of time. If the tracked value reaches a configurable value, the AS can suppress that route until a later time. Because this can affect reachability, an AS can be strategic about how it uses this technique for certain prefixes. For example, more specific prefixes could be more aggressively suppressed (lower thresholds), while routes to known destinations that require high availability could be allowed higher thresholds.

Peering at IXPs

In the previous topics we talked about ASes' business relationships. ASes can either peer with one another directly or they can peer at Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) which are infrastructures that facilitate peering but also provide more services.

What are IXPs?

IXPs are physical infrastructures that provide the means for ASes to interconnect and directly exchange traffic with one another. The ASes that interconnect at an IXP are called participant ASes. The physical infrastructure of an IXP is usually a network of switches that are located either in the same physical location, or they can be distributed over a region or even at a global scale. Typically, the infrastructure has fully redundant switching fabric that provides fault-tolerance, and the equipment is usually located in facilities such as data centers to provide reliability, sufficient power and physical security.

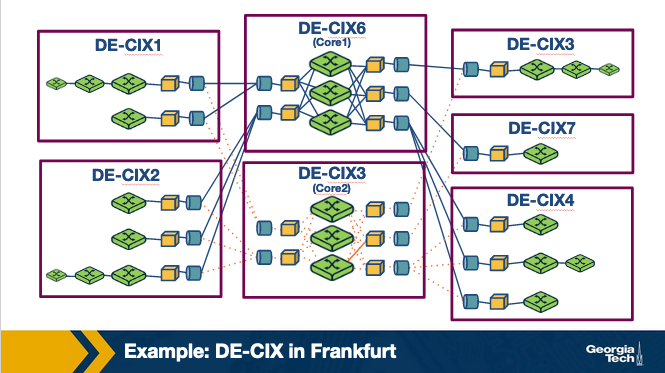

For example, in the figure below we see an IXP infrastructure (2012), called DE-CIX that is located in Frankfurt, Germany. The figure shows the core of the infrastructure (noted as 3 and 6) and additional sites (1-4 and 7) that are located at different colocation facilities in the area.

Why have IXPs become increasingly popular and are important to study?

Some of the most important reasons include:

- IXPs are interconnection hubs handling large traffic volumes: A 2012 study by Ager et al. analyzed a large European IXP and showed the presence of more than 50,000 actively used peering links! For some large IXPs (mostly located in Europe), the daily traffic volume is comparable to the traffic volume handled by global Tier 1 ISPs.

- Important role in mitigating DDoS attacks: As IXPs have become increasingly popular interconnection hubs, they are able to observe the traffic to/from an increasing number of participant ASes. In this role, IXPs can play the role of a “shield” to mitigate DDoS attacks and stop the DDoS traffic before it hits a participant AS. There are a plethora of DDoS events that have been mitigated by IXPs. For example, back in March 2013, a huge DDoS attack took place that involved Spamhaus, Stophaus, and CloudFare. At the lecture on Security, we will look into specific techniques that IXPs have to mitigate DDoS based on BGP blackholing.

- “Real-world” infrastructures with a plethora of research opportunities: IXPs play an important role in today's Internet infrastructure. Studying this peering ecosystem, the end-to-end flow of network traffic, and the traffic that traverses these facilities can help us understand how the Internet landscape is changing. IXPs also provide an excellent “research playground” for multiple applications. Such as security applications. For example BGP blackholing for DDoS mitigation, or applications for Software Defined Networking.

- IXPs are active marketplaces and technology innovation hubs: IXPs are active marketplaces, especially in North America and Europe. They provide an expanding plethora of services that go beyond interconnection, for example DDoS mitigation, or SDN-based services. IXPs have been evolving from interconnection hubs to technology innovation hubs.

What are the steps for an AS to peer at an IXP?

Each participating network must have a public Autonomous System Number (ASN). Each participant brings a router to the IXP facility (or one of its locations in case the IXP has an infrastructure distributed across multiple data centers) and connects one of its ports to the IXP switch. The router of each participant must be able to run BGP since the exchange of routes across the IXP is via BGP only. Each participant has to agree to the IXP's General Terms and Conditions (GTC).

Thus, for two networks to publicly peer at an IXP (i.e., use the IXP's network infrastructure to establish a connection for exchanging traffic according to their own requirements and business relationships), they each incur a one-time cost for establishing a circuit from their premises to the IXP, a monthly charge for using a chosen IXP port (higher port speeds are more expensive), and possibly an annual fee for membership to the entity that owns and operates the IXP. In particular, exchanging traffic over an established public peering link at an IXP is in principle “settlement-free” (i.e., involves no from of payment between the two parties) as IXPs typically do not charge for exchanged traffic volume. Moreover, IXPs typically do not interfere with the bilateral relationships that exist between the IXP's participants, unless they are in violation of the GTC. For example, the two parties of an existing IXP peering link are free to use that link in ways that involve paid peering, or some networks may even offer transit across an IXP's switching fabric. Depending on the IXP, the time it takes to establish a public peering link can range from a few days to a couple of weeks.

Why networks choose to peer at IXPs?

- Keeping local traffic local. In other words, the traffic that is exchanged between two networks does not need to travel unnecessarily through other networks if both networks are participants in the same IXP facility.

- Lower costs. Typically peering at an IXP is offered at lowered cost than eg relying on third-parties to transfer the traffic charging based on volume.

- Improved network performance due to reduced delay.

- Incentives. Critical players in today's Internet ecosystem often “incentivize” other networks to connect at IXPs. For example, a big content provider may require another network to be present at a specific IXP(s) in order to peer with them.

Services that IXPs provide

- Public peering: The most well-known use of IXPs is public peering service - in which two networks use the IXP's network infrastructure to establish a connection to exchange traffic based on their bilateral relations and traffic requirements. The costs required to set up this connection are - one-time cost for establishing the connection, monthly charge for using the chosen IXP port (those with higher speeds are more expensive) and perhaps an annual fee of membership in the entity owning and operating the IXP. However, the IXPs do not usually charge based on the amount of exchanged volume. They also do not usually interfere with bilateral relations between the participants unless there is a violation of the GTC. Even with the set-up costs, IXPs are usually cheaper than other conventional methods of exchanging traffic (such as relying on third parties which charge based on the volume of exchanged traffic). IXP participants also often experience better network performance and QoS because of reduced delays and routing efficiencies. In addition, many companies that are major players in the Internet space (such as Google) incentivize other networks to connect at IXPs by making it a requirement to peering with them.

- Private peering: Most operational IXPs also provide a private peering service (Private Interconnects - PIs) that allow direct traffic exchange between two parties of a PI and don't use the IXP's public peering infrastructure. This is commonly used when the participants want a well-provisioned dedicated link capable of handling high-volume, bidirectional and relatively stable traffic.

- Route servers and Service level agreements: Many IXPs also include service level agreements (SLAs) and free use of the IXP's route servers for participants. This allows participants to arrange instant peering with a large number of co-located participant networks using essentially a single agreement/BGP session.

- Remote peering through resellers: Another popular service is IXP reseller/partner programs. This allows third parties to resell IXP ports wherever they have infrastructure connected to the IXP. These third parties are allowed to offer the IXP's service remotely, which allows networks that have little traffic to also use the IXP. This also enables remote peering - networks in distant geographic areas can use the IXP.

- Mobile peering: Some IXPs also provide support for mobile peering - a scalable solution for interconnection of mobile GPRS/3G networks.

- DDoS blackholing: A few IXPs provide support for customer-triggered blackholing, which allows users to alleviate the effects of DDoS attacks against their network.

- Free value-added services: In the interest of ‘good of the Internet', a few IXPs such as Scandinavian IXP Netnod offer free value-added services like Internet Routing Registry (IRR), consumer broadband speed tests9, DNS root name servers, country-code top-level domain (ccTLD) nameservers, as well as distribution of the official local time through NTP.

Peering at IXPs: How Does a Route Server Work?

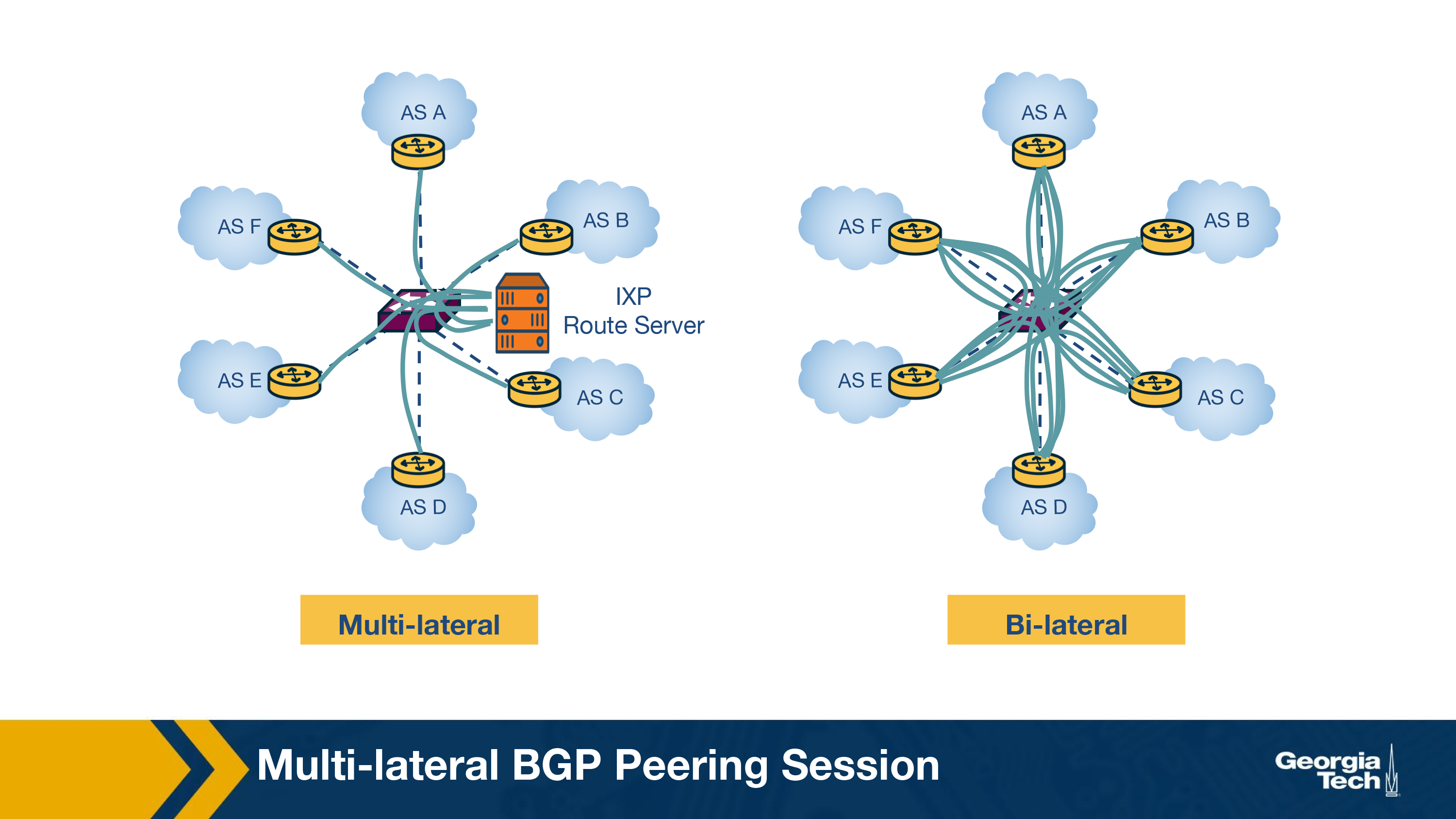

Generally, the manner in which two ASes exchange traffic through the switching fabric was utilizing a two-way BGP session, called a bilateral BGP session. Since there has been an increasing number of ASes peering at an IXP, we have another challenge to accommodate an increasing number of BGP sessions. Obviously this option does not scale with a large number of participants. To mitigate this some IXPs operate a route server, which helps to make peering more manageable. In summary, a Route Server (RS):

- Collects and shares routing information from its peers or participants that connects with (i.e. IXP members that connect to the RS).

- Executes it's own BGP decision process and also re-advertise the resulting information (I.e. best route selection) to all RS's peer routers.

The figure below shows a multi-lateral BGP peering session, which is essentially an RS that facilitates and manages how multiple ASes can “talk” on the control plane simultaneously.

How does a route server (RS) maintain multi-lateral peering sessions?

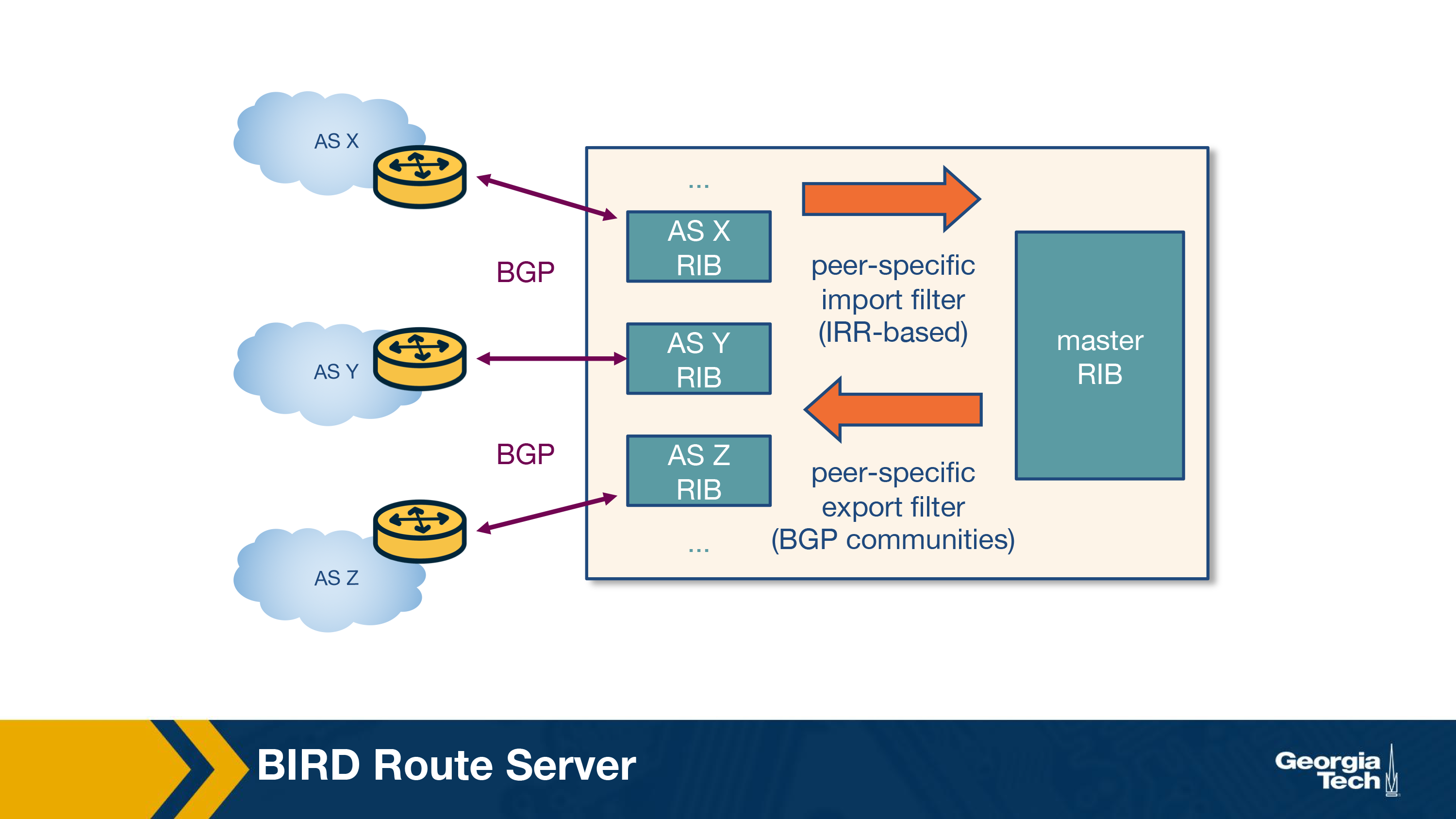

Let's look at a modern RS architecture in the figure below to understand how RSes work. A typical routing daemon maintains a Routing Information Base (RIB) which contains all BGP paths that it receives from its peers - the Master RIB. The router server also maintains AS-specific RIBs to keep track of the individual BGP sessions they maintain with each participant AS.

RSes maintain two types of route filters:

- Import filters are applied to ensure that each member AS only advertises routes that it should advertise,

- Export filters which are typically triggered by the IXP members themselves to restrict the set of other IXP member ASes that receive their routes. Let's look at an example where AS X and AS Z exchange routes through a multi-lateral peering sessions that the route server holds.

Steps:

- In the first step, AS X advertises a prefix p1 to the RS which is added to the route server's AS X specific RIB.

- The route server uses the peer-specific import filter, to check whether AS X is allowed to advertise p1. If it passes the filter, the prefix p1 is added to the Master RIB.

- The route server applies the peer-specific export filter to check if AS X allows AS Z to receive p1, and if true it adds that route to the AS Z-specific RIB. Now, RS advertises p1 to AS Z with AS X as the next hop.

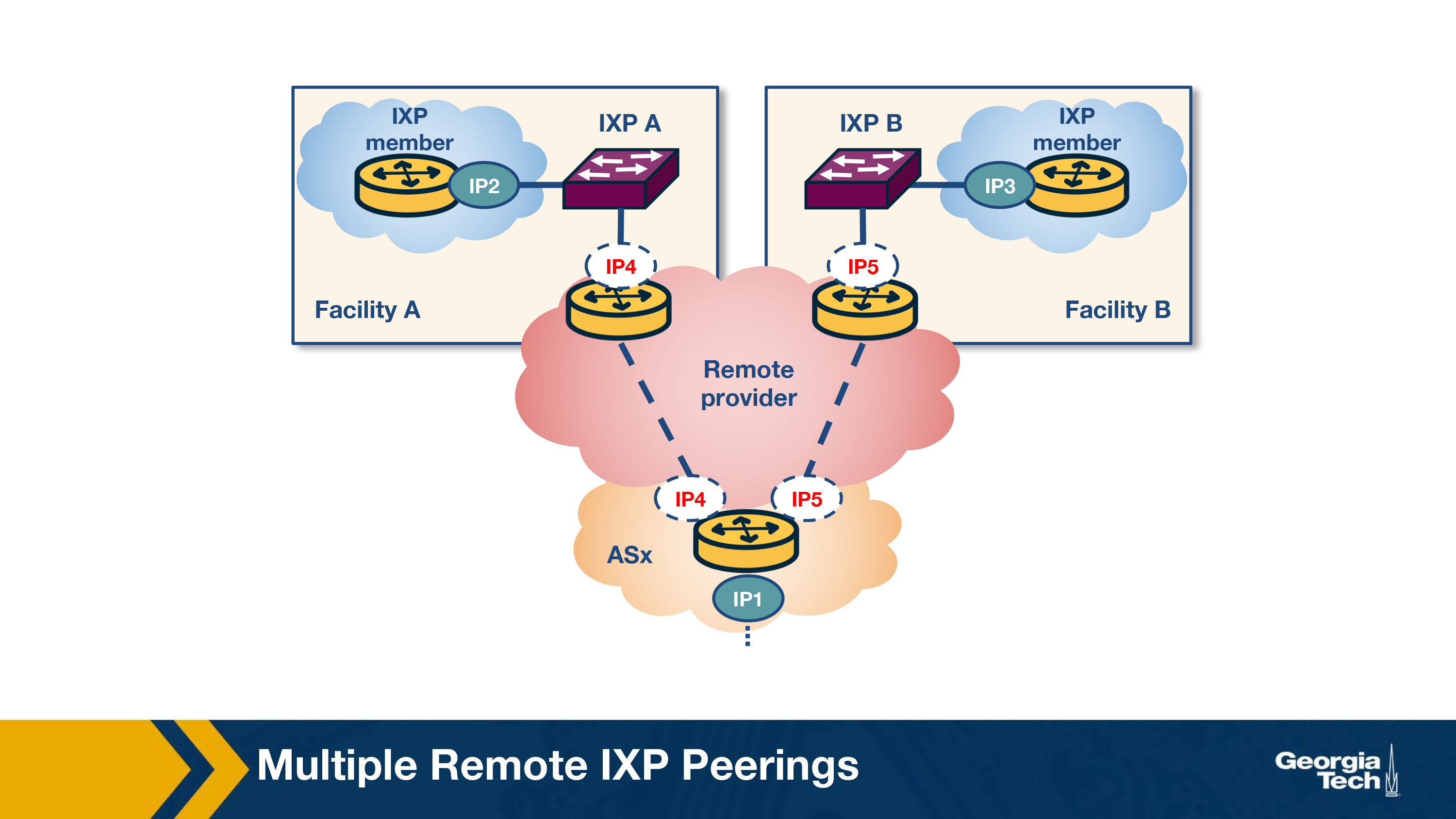

Remote Peering

What is remote peering?

Remote peering (RP) is peering at the peering point without the necessary physical presence. The remote peering provider is an entity that sells access to IXPs through their own infrastructure. RP removes the barrier to connecting to IXPs around the world, which in itself can be a more cost-effective solution for localised or regional network operators.

How to detect remote peering?

An interesting problem is how we can tell if an AS is directly connected to an IXP or it is connected through remote peering. Researchers have studied this problem and identified methodologies to detect remote peering with high accuracy and by performing experiments with a large number of IXPs.

The primary method of identifying remote peering is to measure the round-trip time (RTT) between a vantage point (VP) inside the IXP and the IXP peering interface of a member. However, this method fails to account for the changing landscape of IXPs today, and even misinfers latencies of remote members as local and local members as being remote. Instead, a combination of methods can achieve detection of remote peering in a more tractable way, some of which include:

- Information about the port capacity: One way to find reseller customers is via port capacities. The capacity of peering port for each IXP member, can be obtained through the IXP website or PeeringDB. IXPs offer to ASes connectivity to ports with capacity typically between 1 and 100 Gbit/s. But resellers usually offer connectivity through their virtual ports with smaller capacities and lower prices.

- Gathering colocation information. An AS needs to be physically present (actually deploy routing equipment) in at least one colocation facility where the IXP has deployed switching equipment. Even though it should easy to locate the colocation facilities where both AS and IXPs are colocated, though in practice this information is imperfect.

- Multi-IXP router inference: An AS can operatesa multi-IXP router which is a router connected to multiple IXPs to reduce operational costs. If a router is connected to multiple IXPs and say, we infer the AS as local or remote to one of these IXPs from a previous step, we can extend the inference to the rest of the involved IXPs based on whether they share co-location facilities or not.

- Private connectivity with multiple existing AS participants: If an AS has private peers over the same router that connects it to an IXP, and the private peers are physically co-located to the same IXP facilities, it can be inferred that the AS is also local to the IXP.

BGP Configuration Verification

Control of BGP configuration is complex and easily misconfigured both at the eBGP configuration level and within an AS, at the iBGP level, where route propagation happens in a full mesh or via “route reflectors”. Configuration languages vary among routing manufacturers and may not be well-designed. Adding to the complexity, is the distributed nature of BGP's implementation.

BGP correctness is defined by two main aspects of persistent routing. They are path visibility and route validity.

- Path visibility - means that route destinations are correctly propagated through the available links in the network.

- Route validity - means that the traffic meant for a given destination reaches it.

The router configuration checker, or rcc, is a tool proposed by researchers, that detects BGP configuration faults. rcc uses static analysis to check for correctness prior to running the configuration on an operational network, before deployment. rcc analyzes router configuration settings and outputs a list of configuration faults.

To analyze single router or a network-wide BGP configuration, rcc will first “factor” the configuration to a normalized model by focusing on how the configuration is set to handle (1) route dissemination, (2) route filtering, and (3) route ranking.

Although rcc is designed to be used prior before running a live BGP configuration, it can be used to analyze the configuration of live systems and potentially detect live faults. In analyzing real-world configurations it was found that most Path Visibility Faults were the result of:

- Problems with “full mesh” and route reflector configurations in iBGP settings leading to signaling partitions

- Route reflector cluster problems

- Incomplete iBGP sessions where an iBGP session is active on one router but not the other.

Route Validity Faults were determined to stem from filtering and dissemination problems. The specific filtering behaviors included legacy filtering policies not being fully removed when changes occur, inconsistent export to peer behavior, inconsistent import policies, undefined references in policy definitions, or non-existent or inadequate filtering. Dissemination problems included unorthodox AS prepending practices and iBGP sessions with “next-hop self”. These issues suggest that routing might be less prone to faults if there were improvements to iBGP protocols when it comes to making updates and scaling.

Because rcc is intended to run prior to deployment, it may help network operators detect issues before they become major problems in a live setting, which often go undetected right away. rcc is implemented as static analysis and does not offer either completeness or soundness; it may generate false positives and it may not detect all faults.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy